A manifesto for reviving biopharma productivity

When it comes to Eroom's Law, some of the most important problems are the boring ones

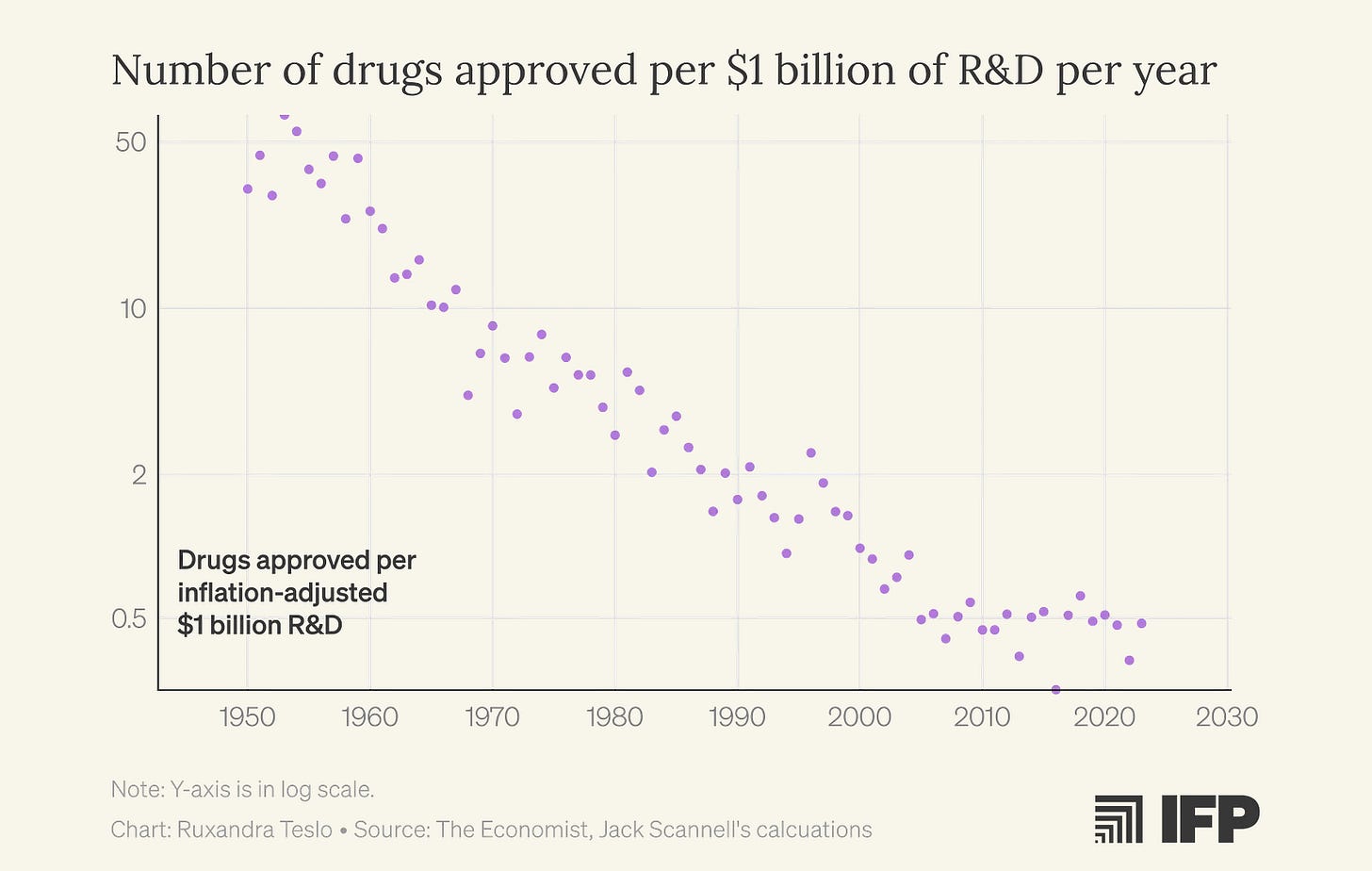

I first encountered Eroom’s Law, the observation that biopharma productivity, measured as new drugs approved per billion dollars of R&D spending, has been steadily declining since the 1960s, halfway through my PhD. The fact that I completed a supposedly world-class undergraduate biology degree without ever hearing about this concept, and then spent another two years in a PhD program before discovering it, now feels damning. If anything deserves a place in Biology 101, it’s the recognition that our ability to turn biological insight into effective medicines has been deteriorating for decades.

Over time, I became somewhat obsessed with this problem. I also discovered that most biologists aren’t. That lack of engagement, I think, fuels a kind of magical thinking: the belief that simply doing “more and better science” will reverse the productivity decline. But we have had more and “better” science for decades. Clearly, we need to start thinking about this differently.

On one hand, I think we should be engaging much more seriously with the predictive validity of our preclinical models. Preclinical models—whether cell lines, organoids, animal systems, or computational approaches—are meant to serve as stand-ins for human patients at the earliest stages of research. But we rarely ask, in a systematic way, how well results in these models actually forecast outcomes in human clinical trials. Predictive validity, in this sense, is not about whether a model is biologically elegant or mechanistically informative, but about whether positive or negative findings meaningfully change the probability that an intervention will succeed in the clinic. Taking predictive validity seriously would require treating preclinical models as forecasting tools—explicitly measuring how their outputs correlate with downstream clinical success and failure—and using that evidence to guide model selection, funding priorities, and translational decision-making.

On the other, I believe we should appreciate the importance of in-human testing (and any type of data obtained from whole humans) much more, realize that nothing is going to replace it and focus on improving clinical development itself.

Earlier this year, I learned that Jack Scannell, who coined Eroom’s Law, is similarly frustrated with the endless list of fashionable “solutions” that hand-wave past these fundamental problems. Since he has written at length about how to think about predictive validity, we ended up focusing on the importance of improving clinical trials for a new article in IFP’s new metascience newsletter, Macroscience.

We think that public debate around improving biopharma productivity often focuses only on the most visible parts of the drug discovery funnel:

Public debates about how to revive productivity in the biopharmaceutical industry tend to be dominated by two camps. Technological optimists usually argue that declining industry outputs relative to investment reflect gaps in biological knowledge, and that advances in basic science will eventually unlock a wave of new therapies. The second camp, which traces its intellectual lineage to libertarian economists, focuses on easing the burden of regulation. In their view, excessive FDA caution has slowed innovation. They propose solutions that largely target regulatory approval: either loosening evidentiary standards or narrowing the FDA’s mandate to focus solely on safety rather than on efficacy.

Both perspectives contain some truth. Yet by focusing on the two visible ends of the drug discovery pipeline, early discovery and final approval, both camps miss the crucial middle: clinical development, where scientific ideas are actually tested in people through clinical trials. This stage is extraordinarily expensive, operationally intricate, and crucially, generates the field’s most consequential evidence. We believe that systematic optimization of this middle stage offers significant untapped leverage and deserves far greater focus.

This piece is also my way of signaling that I’ll be spending much more of my time on this issue—and that a longer list of concrete proposals is coming soon. In the meantime, if you have ideas, especially around regulatory changes or anything that could meaningfully improve clinical trials, I’d love to hear from you.

I think this topic has been relatively ignored compared to its importance, as I argue in the piece:

Clinical Trial Abundance, a framework for scaling and accelerating human trials, stresses the importance of optimizing clinical development. We already have a menu of promising solutions. Increasing regulatory transparency, strengthening clinical trial infrastructure through targeted investment, applying the Australian Phase I model in the US, relaxing excessive Good Manufacturing Practices requirements for early-stage development, and enabling remote and decentralized trials are just a few examples. But many of these ideas remain underdeveloped: the specific policy mechanisms, implementation pathways, and operational models are underspecified and insufficiently advocated for.

For the US, the ideal strategy lies in combining world-class science with highly agile clinical development. Yet clinical development has long been overshadowed by basic research, largely because it is operational, less glamorous, and thus, poorly suited for study within academic frameworks. This persistent asymmetry in attention must be addressed.

We believe one reason clinical development has been systematically underweighted in discussions of how to improve biopharma productivity is cultural. Constructing elegant, internally coherent explanatory narratives is deeply attractive to scientists and academics.

These narratives are intellectually satisfying: they reduce biological complexity to legible mechanisms, assign clear causal roles to specific targets or pathways, and offer the reassuring sense that progress follows from understanding. They are also far easier to communicate, teach, fund, and publish than the messy, probabilistic reality of learning from human trials.

Through multiple waves of technology, from computer-aided drug design, via high-throughput screening, recombinant proteins, and genomics, techno-optimists have overestimated the innovation yield of the hot new thing. Again and again, scientists have placed too much confidence in the power of “biological insights,” or pre-clinical mechanistic foresight. Attention naturally concentrates on the few drugs that succeed, so it is easy to construct post hoc narratives of deliberate design.

Moreover, the biotech ecosystem rewards storytelling. From venture capital pitch decks to internal R&D reviews, a compelling mechanistic narrative makes a program easier to fund and justify.

Yet the empirical record shows that mechanistic foresight provides, at best, rough guidance. Drug discovery is better seen as an iterative design-make-test loop, in which real-world human data repeatedly guide the next cycle of design. Progress may depend less on hitting the best therapeutic hypothesis from the start, and more on generating a broad range of plausible attempts and winnowing them quickly based on clinical feedback. What works survives; what does not is modified or abandoned.

In previous work, we described this dynamic as clinical selection: a process in which the clinic, rather than preclinical mechanistic theory, supplies the decisive information about which interventions genuinely benefit patients. We contrasted this with the familiar “intelligent design” narrative, which imagines a linear march from target identification to rational design to cure.

Many of the most successful drugs did not emerge from deep mechanistic foresight, but from iterative, empirical exploration. The clinic functioned as an evolutionary engine. Anti-TNF drugs failed in their original indication before becoming foundational in autoimmune disease; statins survived only because physicians noticed striking patient responses after the field had largely moved on; and drugs like Avastin and Gleevec accumulated unexpected indications as human studies reshaped both their use and their mechanistic stories over time.

GLP-1 agonists offer a contemporary case in point. The earliest drugs in this class, such as exenatide, were developed for diabetes and aimed primarily at improving glycemic control. Later agents like liraglutide offered better pharmacological characteristics, making weight-loss applications more feasible. Even so, many experts thought that meaningful weight reduction was unattainable, because it required higher doses that caused unacceptable nausea. That side effect was overcome through clinical experimentation: gradual dose escalation markedly improved tolerability, enabling liraglutide’s approval for obesity in 2014.

Once a strong clinical signal existed, investment shifted back to refining the molecules themselves. Through extensive screening and chemical optimization of stability, potency, and half-life, Novo Nordisk developed semaglutide, a more durable agent suitable for weekly dosing. Clinical experimentation in patients without diabetes then delivered another surprise: patients lost far more weight than most experts predicted. At higher doses, semaglutide showed ~12.4% weight loss baseline body weight vs. placebo, a result that had previously been seen as out of reach for pharmaceutical interventions.

On the back of these results, semaglutide became one of the most commercially and clinically successful medicines of the modern era. Ongoing trials continue to reveal additional, unforeseen benefits of GLP-1 agonism, including reductions in cardiovascular events that appear independent of weight loss, as well as improvements in liver disease.

Only in the last couple of years have researchers started to stitch together a more complete mechanistic picture of GLP-1–driven weight loss, integrating evidence from animal studies, neuroimaging, gut–brain signalling, adipose-tissue biology, liver metabolism, and long-duration receptor pharmacology. Crucially, this understanding emerged after, not before, the clinical breakthroughs. And the mechanistic model remains incomplete, while the clinical outcomes are unambiguous, a clear case where human trials revealed the therapeutic potential before mechanistic biology could explain it.

Good observation regarding learning of Eroom’s law. I learned of it after entering industry and agree that it should be discussed in academic circles as widely as industry to create a sense of “pulling together” from the outset

I continue to be surprised by the relative absence of genuine innovation on the "boring middle bit" of clinical research (the component of R&D that consumes perhaps 66% of total spend). It may well be the case the traditional CRO sector, like all incumbents, will resist radical changes to its business model and other, more nimble and agile players, with less legacy infrastructure will take up the slack.

Let's hope that the adage of necessity being the mother of invention will play out again.