Building in the world of flesh needs regulatory transparency

We want more drugs, but we make it the hardest to achieve that

Building in the world of flesh is hard, but worthy

In the last few months, someone working in crypto trading derogatorily called me a “biofoid”. That is because I studied biology and worked in the field, despite being intelligent. Why, he wondered, did I waste my brains and potential on such a cursed topic? I could have done crypto trading and made money. This stuck with me and caused somewhat of an identity crisis. If people are wondering why I have written less recently, part of it is struggling with the inferiority of being a biofoid.

Why, why, why? Why am I a biofoid? There are many answers to this. One of them is that I could not “hack” my brain to care about crypto trading, even if I wanted to. I have been always interested in two topics: biology and something that can be approximated as “culture and society”, but never in crypto or trading. That might make me inferior in the eyes of some, but I cannot change who I am, even if I wanted to. I am, unfortunately, a biofoid… The answer also lies in the following interaction from The Lord of the Rings, one that I have read repeatedly in the last months of torment to remind me I might have a use in this world.

The closest thing to orcs in this world might be disease (of the soul and flesh). And there is some good in this world: people and their lives. And hard as it might be, that is worth fighting for. Building in the world of flesh, or doing biotech, is arduous like walking into Mordor for multiple reasons; but it’s also crucial. And even though I am relegated to the underclass of biofoids, I can at least try and be a useful biofoid, as opposed to a useless one.

A way to do that, I reason, is by drawing attention to the issues facing biotech.

In a recent NYT Op-Ed, Rep Jake Auchincloss writes that we should focus more on building in the world of atoms:

Our IRL terrain especially needs more innovation in what’s called tough tech. Tough tech companies use frontier science and engineering to solve the world’s hardest material problems, from climate change to disease, by inventing technologies in fields like fusion energy, cell biology and A.I.-powered robotics.

I wholeheartedly agree. Paradoxically, we bottleneck these innovations the most, often through misguided policies/regulations. And no domain is bottlenecked the hardest than that which gives us what we value the most: health. Biotech/Pharma, or building in the world of not mere atoms, but Flesh, is that which is made hardest. Not just through regulations, but also through constant vilification of pharma companies, despite the immense benefit they bring compared to dollars invested.

We must fix clinical development; increasing transparency is a way.

Imagine you live in a country with very strict laws and very long trials. Yet, you only have vague guidance regarding what the laws are and no previous court transcript, just very short summaries of outcomes. The only way you can get a glimpse into what might be needed of you is by hiring expensive and inefficient lawyers, that you have very little information on how to judge, and which provide you with inconsistent advice. This is exactly what drug developers who submit drugs for approval with the FDA face: a long and arduous process that can take a decade or more, with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake and very little in the way of a reference for what the FDA might want. The only way to glimpse into that is by relying on third party vendors: manufacturing consultants, CROs for organizing trials, regulatory consultants. These are the equivalents of the inefficient but expensive lawyers in the country-with-no-court-transcripts scenario.

While we are all excited about sexy new science that makes it to the cover of Nature, the truth is that success in biotech depends in large part on the much more opaque and expensive process that follows the sexy new science: clinical development, or bringing a product to the clinic in the form of getting a drug approved. This can take up to a decade and can cost more than a billion dollars per drug approved. Yet clinical development is not really a sexy topic to talk about. But we ignore optimizing it at our own peril: China is starting to massively eat our lunch in early stage biotech, precisely because they take it seriously. U.S. still has a major advantage in innovative new science, but China has been focusing on streamlining this more “boring”, yet crucial part of biotech success, as this twitter thread very well puts it. US makes the science, they get the gains.

There are many things to be said about how to make this better. But one of the simplest, and most powerful, would be to make the clinical development process less opaque. Much has been said about the issues facing science, with a lot of ire directed at the publication system. If you think that is bad, wait until you find out about the “publication system” for clinical development: basically nothing, no blueprint. It’s not that the equivalent of scientific papers stays locked behind paywalls: it simply cannot be accessed. As a result, it can feel as if knowledge about clinical development simply disappears behind FDA’s walls.

But in reality, none of it is lost. Every interaction with the FDA, every clinical protocol, every amendment and reviewer comment is meticulously documented. All of this information lives inside CTDs (Common Technical Documents) that routinely span thousands of pages. A CTD is not a summary, but a full chronicle of development: preclinical toxicology data, trial design rationales, adverse event logs, detailed manufacturing methods, and the entire back-and-forth between sponsor and regulator. To outside observers, this record is invisible. To those who have seen one, it is immediately clear that CTDs are the most comprehensive archives of real-world clinical development practice ever assembled. However, this information is very hard to access. Bound by statutory law, the FDA treats most of it as confidential, especially anything seen as a trade secret or business-sensitive. In practice, this results in heavily redacted FOIA releases that lack the technical detail that drug developers would require.

There are very direct ways in which increasing the transparency of clinical development would decrease costs: for example, by streamlining the inefficient back and forth with the FDA. But there are also more subtle, second order problems arising from the current opacity that could be alleviated. One of the second order problems created by a lack of transparency, is the culture of safetyism that is characteristic of biotech development, a topic I have written about before. To summarize this, a generally valid perception of regulatory harshness combined with lack of transparency leads players to overshoot, even in cases where rules are actually favourable to disruption. This leads to an overall tendency to stick to the status quo (as is the case with the lack of adoption of risk-based monitoring (RBM), a more innovative and less costly way of running clinical trials, despite FDA guidance favouring it, explained here). Meri Beckwith, who runs a start-up called Lindus Health, focused on running faster and more efficient clinical trials, explains the dynamics underpinning this over-safetyism:

We see a surprising reluctance from pharma to accept more innovative trial designs and methods (like centralized remote monitoring, risk based monitoring and decentralized/hybrid trial designs), even when these are specifically encouraged in FDA guidance, and demonstrably lead to lower costs and higher quality data. This stems from the massive amounts of inertia in these huge organisations, limited competitive pressure to change.

In a recent proposal for IFP, which I see as a continuation of the Clinical Trial Abundance Project started last year, I suggested a solution to this: acquiring CTDs from failed companies and make them available to the public through a philantropic fund. This bypasses the harsh trade secret laws the FDA is bound by.

The value

The idea got a positive response that was beyond what I had envisioned, especially from biotech founders and experienced operators. But some had understandable questions about the potential. In some ways, it is hard to explain the value of something that we do not have access to, so it’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem. I think many confused this with standard “IP rescue”, which is the idea of reviving potentially “valuable” drugs from a pile of discarded, rejected things.

But that’s not it: what we are trying to build here is “regulatory know-how” for the commons. The value is not in an otherwise ignored asset that could be repurposed to great success, but in revealing both the “boring” details of clinical development as well as the regulatory back-and-forth underpinning it. Again, this miscallibration of where the value lies is reminiscent of how we cheer on new breakthrough scientific discoveries, yet we ignore the part that’s the hardest: bringing a drug into clinic. The full positive implications of releasing CTDs of such an initiative will be elaborated more at length in a longer memo, where other, non-philantropic solutions will be explored.

However, in the meantime, I would like to highlight how positive the response to the release of heavily redacted CRLs (complete response letters) by the FDA has been on biotech X, including from founders and journalists that have been mostly critical of this admin. Adam Feuerstein himself, known for really not liking this admin or this FDA had to say “kuddos to the FDA”. That’s a big deal.

But CRLs are nothing compared to full CTDs. And if people are excited about the release of *redacted* CRLs (which contain something like 1/100 of the information in a CTD), well, that’s a good sign CTDs would be valuable.

A CTD (Common Technical Document) is the international format for drug approval submissions. It contains everything: the chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) data that so often delay biotechs and cause hundreds of millions in lost revenue, complete clinical protocols and datasets, and the detailed back-and-forth between companies and FDA reviewers.

I recently saw this for the first time, thanks to Brian Finrow of LumenBio, who generously shared with me the CTD he had acquired for $25,000 from a failed biotech. Thousands of pages of what look like “boring details” are in fact the practical playbook of how drugs succeed—or fail—through the FDA.

For small innovators, this kind of information is invaluable. Large pharmaceutical incumbents already have private archives of CTDs and decades of institutional know-how. That gives them a structural advantage. This is confirmed by empirical results from the economics of innovation. When it comes to the biopharmaceutical industry, regulatory complexity favours large incumbents. A landmark analysis of 766 new molecular entities submitted to the FDA between 1979 and 2000 found that between 30–55% of the advantage enjoyed by large firms in approval timelines can be attributed to familiarity with the regulatory processes alone. A recent analysis of FDA medical device deregulation between 1980 and 2015 found that reclassifying certain devices from Class II to the lower scrutiny Class I led to both higher quality and quantity of innovation, without compromising safety. Notably, smaller firms saw the greatest benefit, with new firm entry increasing by 200%. The author attributes this to reduced approval delays and a flatter regulatory learning curve.

Start-ups, by contrast, must spend heavily on consultants, often duplicating mistakes that could have been avoided if they had access to the same regulatory precedent. Regulatory transparency is, in this sense, antitrust done right: it levels the playing field without disrupting the market.

Overall, this ends up hurting everyone, even large pharmaceutical companies. This is due to another second order effect of regulatory opacity: the lack of a true market for third party vendors like CROs that organize clinical trials. While big pharma companies have a leg up due to their regulatory experience when compared to smaller biotechs, the same dynamic whereby opacity favours incumbents as opposed to more nimble, new entrants, plays out when it comes to market for third party vendors.

Large pharma can do more stuff in-house but they still outsource certain parts of clinical development, like organizing clinical trials to CROs. And these CROs are not competing on efficiency or price, but “regulatory know-how”. This is not a novel concept: the idea that information asymmetry creates inefficient markets is a well-known concept in economic literature, pioneered by Nobel Prize laureate Joseph Stiglitz. In the end, everyone ends up paying more for clinical trials due to this market inefficiency. This dynamic is brilliantly explained by a widely shared article that aims to partially answer the question of why clinical trials have become so expensive in the US. It showcases just how inefficient the market for CROs is. I recommend the whole article, which is both funny and instructive, but the conclusion is particularly good:

Why is this industry so cursed? Some hypotheses:

There is fundamentally a lack of talent flowing into the space, because everyone smart is eaten by tech or finance (the only reason I had any insight into this at all was because I was an ML-focused engineer in a biotech company heavily funded by tech VCs)

Everyone who is reasonably smart and joins this industry eventually either leaves or simply gives up on any hope of positive change to the status quo; to justify the state of affairs to themselves, they invent nonsensical copes about how things couldn’t be any other way

The massive amount of undocumented specialist knowledge that you need to efficiently run a clinical development program strongly favors incumbents, preventing new market entrants from easily competing on the basis of cost or competenceーe.g., it doesn’t matter if your firm has 170 IQ engineers if they simply don’t know all the One Weird Tricks about how to get around the FDA’s catch-22s

Because the cost of failure is so high, well-capitalized companies will always favor established methods, even if they are slow and inefficient, as long as they present a reasonable chance of getting the job done eventually

To effectively run a clinical trial, you must hire on a large number of ex-pharma professionals for their specialized knowledge, and that fundamentally degrades the culture of the company beyond recognition

The FDA is not evil

I think the common wisdom within many of the more online, rationalist circles, is that the FDA is simply too risk-averse, has bad intentions and stuff along these lines.

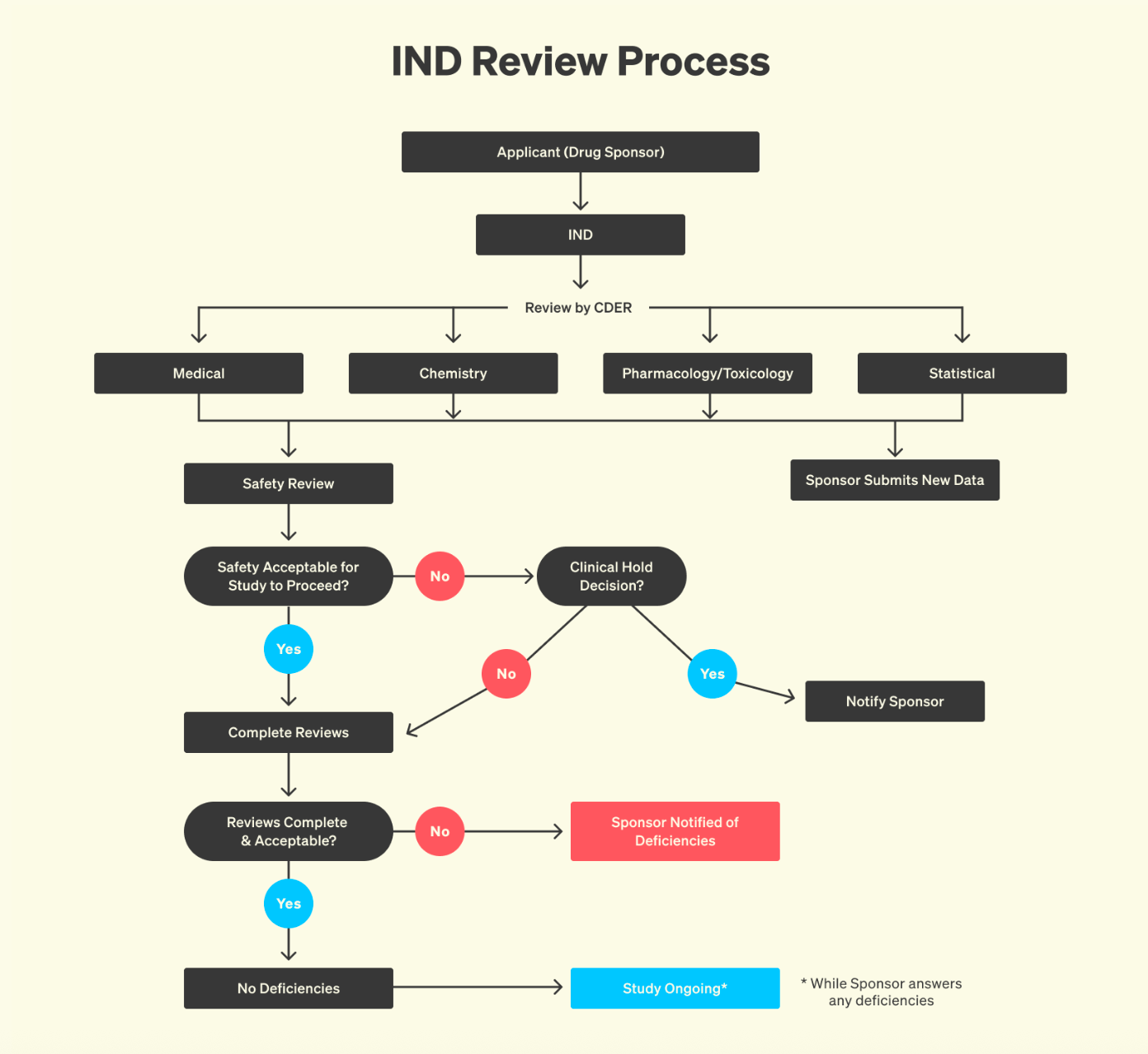

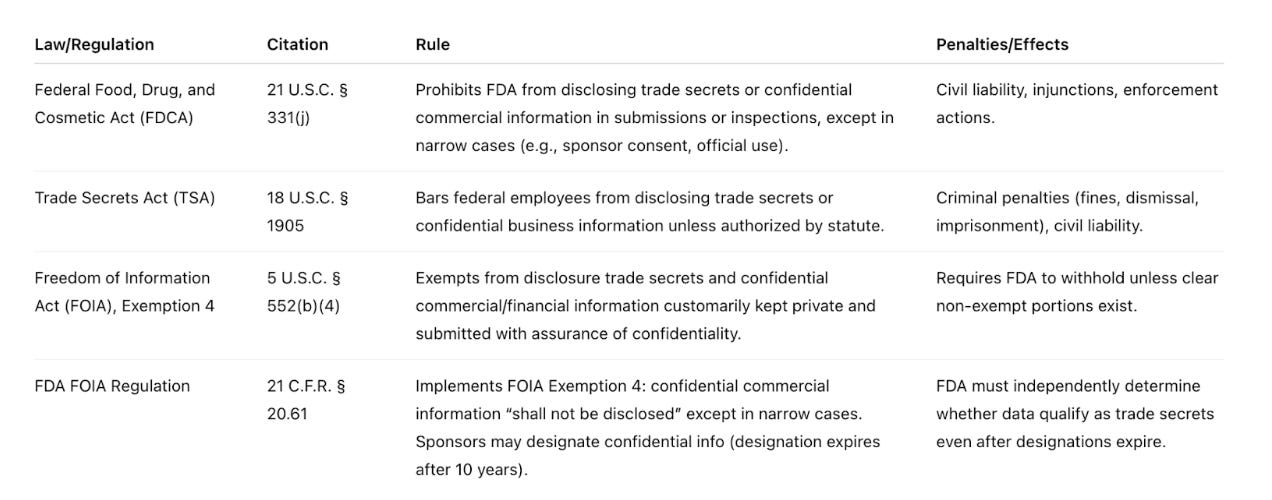

But the FDA cannot solve the problem of transparency alone. The agency is severely legally constrained and risk-averse for good reason. Unfortunately, the FDA cannot simply release CTDs, even from failed companies or old drugs, no matter how valuable they might be to the public. The agency is legally constrained by overlapping statutes, among which the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, the Trade Secrets Act, and FOIA Exemption 4, all of which prohibit the disclosure of what could be considered trade secrets.

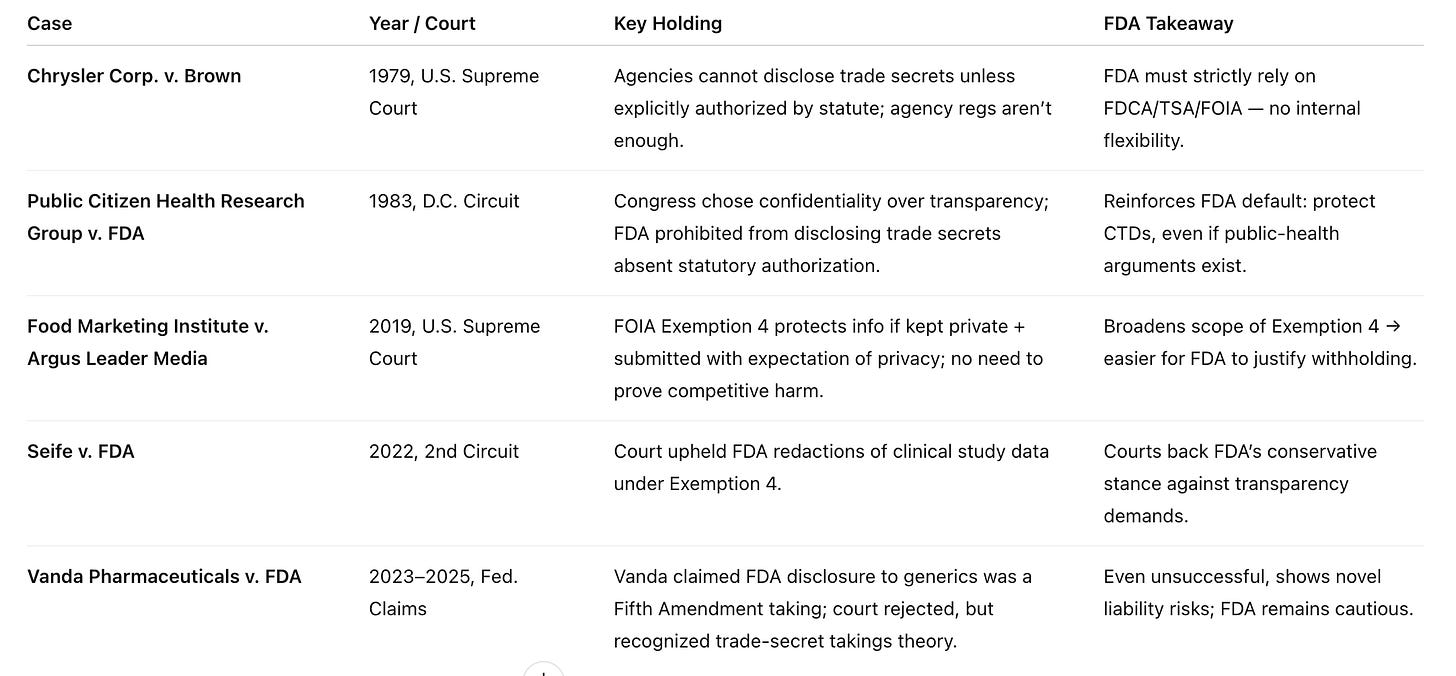

Courts have repeatedly reinforced this stance, with relevant cases summarized below:

A case that shows just how strict the current legal environment is Vanda vs FDA (2023-2025). In May 2023, Vanda Pharmaceuticals sued the FDA in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, alleging that the agency improperly disclosed confidential trade-secret information related to its drugs Fanapt and Hetlioz to generic drug applicants. Vanda argued that dissolution specifications and manufacturing details were revealed. The company framed its complaint as a Fifth Amendment “takings” claim, saying the government had taken proprietary information without compensation. By January 2024, the court allowed the takings claim to move forward but dismissed the implied contract claim, meaning it found no contractual duty breached by the FDA. In January 2025, the court ruled against Vanda, finding that much of the information in question was not originally developed by Vanda but was instead proposed or suggested by the FDA itself. As a result, it was not considered a protected trade secret belonging to Vanda.

Even though this ridiculous case was ultimately not won by Vanda, the court still had to parse patents, filings, and confidentiality rules just to conclude there was nothing protectable at stake. The very fact that such a case could wind its way through years of constitutional litigation shows how rigid the system is.

The solution requires either:

Legislative change: changing law to allow the FDA to release CTDs of failed companies or from old drugs that no longer hold commercial value.

Philanthropic or federal acquisition: Funding a dedicated effort to buy orphaned CTDs out of bankruptcy and place them in the commons.

More to come….

You are doing genuinely valuable unlike crypto creatures.

"In the last few months, someone working in crypto trading derogatorily called me a “biofoid”. That is because I studied biology and worked in the field, despite being intelligent. Why, he wondered, did I waste my brains and potential on such a cursed topic? I could have done crypto trading and made money. This stuck with me and caused somewhat of an identity crisis. If people are wondering why I have written less recently, part of it is struggling with the inferiority of being a biofoid."

First of all, seriously, I would try to get not too worked up about things people tell you while arguing about politics on the Internet. People are nasty when arguing about politics, and people are nasty on the Internet, and...

Second, you seem to have a very strong desire to improve the world, which crypto probably isn't going to do (and he specifically mentioned making money). Biology obviously is quite relevant to that even if it's not mathematically tractable. (And you might have a bit of an edge if you actually are good at math.) So you have different values from your interlocutor, and shouldn't be surprised when you come up with different life goals. If you start from different axioms, you get different results.

Third, the 'foid' thing is a contraction of the antifeminist term 'femoid', implying women aren't real people. So you're probably not going to please him no matter what.

If the blog's getting in the way of your more important work, that's one thing. But letting yourself get into identity crises because someone said something nasty to you on the Internet...I realize it's kind of an occupational hazard of dealing with ideas and taking them seriously, but I'd say it's one to avoid.