Of course motherhood drives the gender wage gap

Discussions around the motherhood wage gap reveal the limits of autism and the benefits of female intuition

When confronted with a new result in quantitative social science, one often has to fall back on what I half-jokingly call “female intuition.” And if you don’t feel you possess any such intuition yourself, you can always borrow from a reliable source: your grandmother. Try channeling an inner voice that simply asks, “Would my grandmother believe this?”. If you’re wholly uninterested in giving women credit for their hard-earned perceptiveness, you can also use the more gender-neutral label that older professionals prefer: “the smell test”, to describe this process.

At this point, you might object: “Ruxandra, this sounds like terrible epistemics. You’re a scientist—how can you endorse swapping rigor for folk wisdom? Would you have us return to the Middle Ages and listen to the female intuition of the Village Witch? “

However, unlike the natural sciences, where female intuition is often a misleading guide, the social world is familiar terrain. We’ve been navigating it since childhood, absorbing its particularities long before we had the vocabulary to describe them. So when a paper’s conclusion lands on the other side of the grandma test, a bit of skepticism is wise.

Thanks to the replication crisis in social psychology, people have become far more discerning about published findings and more likely to apply their female intuition. Hence the now-familiar quip: “Findings in social psychology are either trivial or false.” Economics, perhaps because its practitioners apply more statistical rigor and are generally smarter, has been spared some of the skepticism directed at other social sciences. But economists are human like everyone else and crucially their jobs also depend on deriving interesting (and surprising) insights from data.

A recent example of how economics can become enamoured with its own methods, at the expense of revealing the truth, was revealed in the renewed debate over the gender wage gap. Conversations about this topic had long been saturated with layers of unhelpful mythology, largely because the topic is so “politically sensitive”. Depending on who you asked, you’d hear wildly different explanations. Many feminists insisted the gender wage gap was primarily the result of discrimination. Red-pill commentators, on the other hand, would tell you women are just stupid.

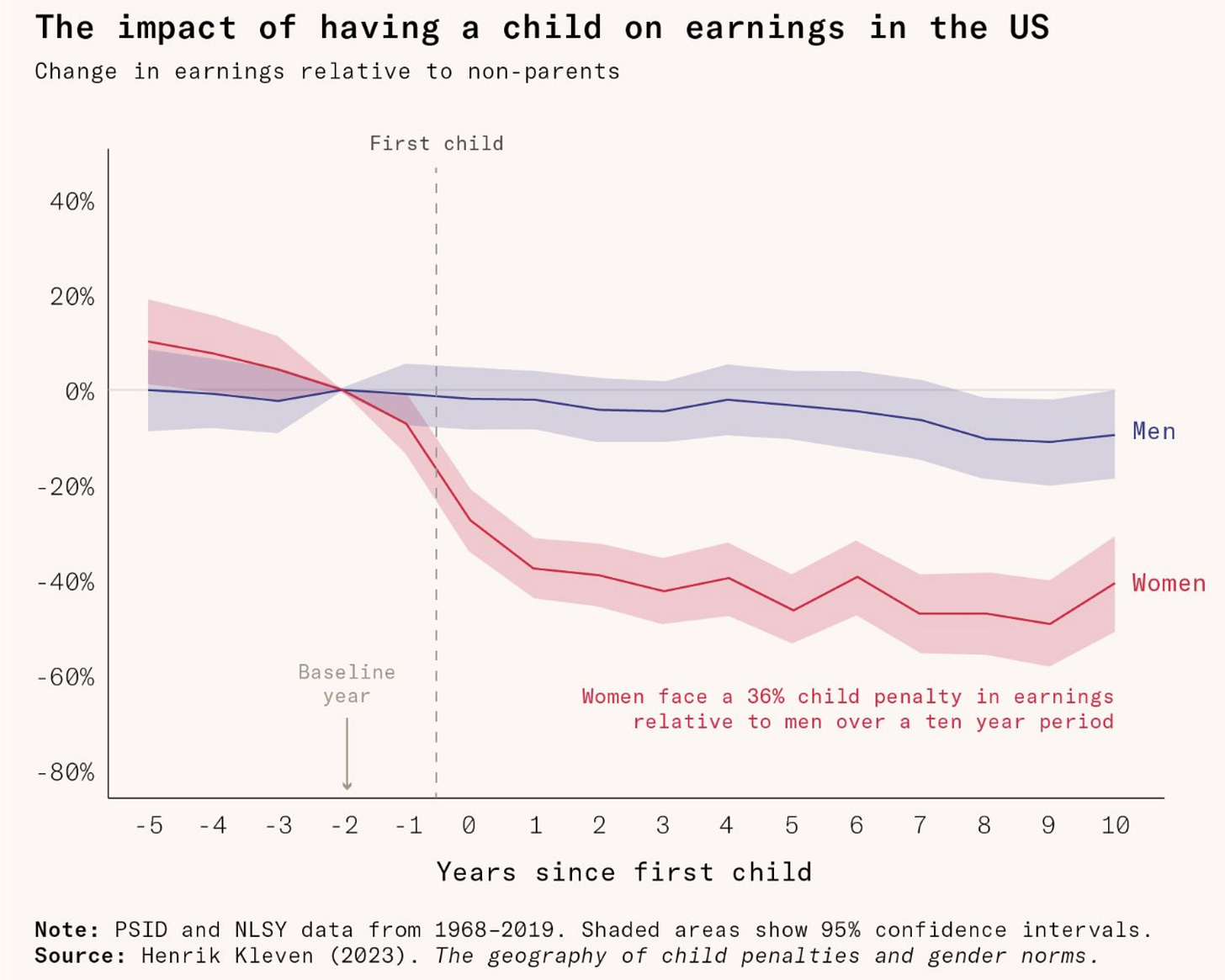

Economists, on the other hand, had long held that in developed countries most of the gender wage gap is attributable to motherhood. The career interruptions, reduced hours, and constrained job choices that follow from having children set women back in their careers, often irreversibly. Shedding light on this topic with empirical studies is what earned economist Claudia Goldin the 2023 Nobel Prize in Economics. In this debate they were, in my opinion, the camp closest to the truth.

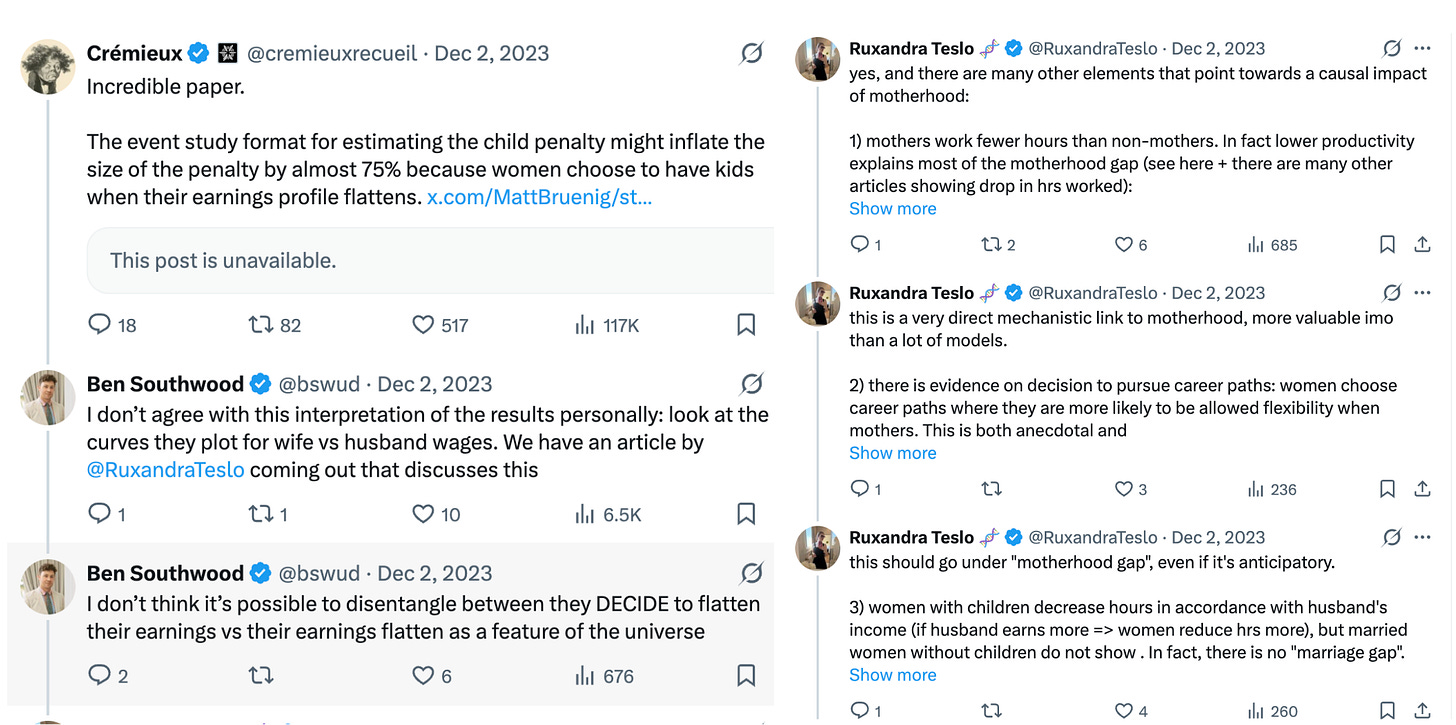

However, beginning in 2023, a new set of papers using IVF as a causal instrument claimed to overturn this consensus. Many people set aside their female intuition and bought into this. The papers that seemed to contradict the motherhood wage gap findings became a popular topic on twitter and on Substack, with surprisingly few questioning their assumptions and design. There were some notable exceptions, such as Ben Southwood, editor of Works in Progress, and Tyler Cowen, one of the few figures in autism-adjacent circles who consistently recognizes the value of female intuition.

I found the results implausible at the time and raised several objections. I shared them publicly on X and included a long footnote about them in my Works in Progress article, “Fertility on demand”.

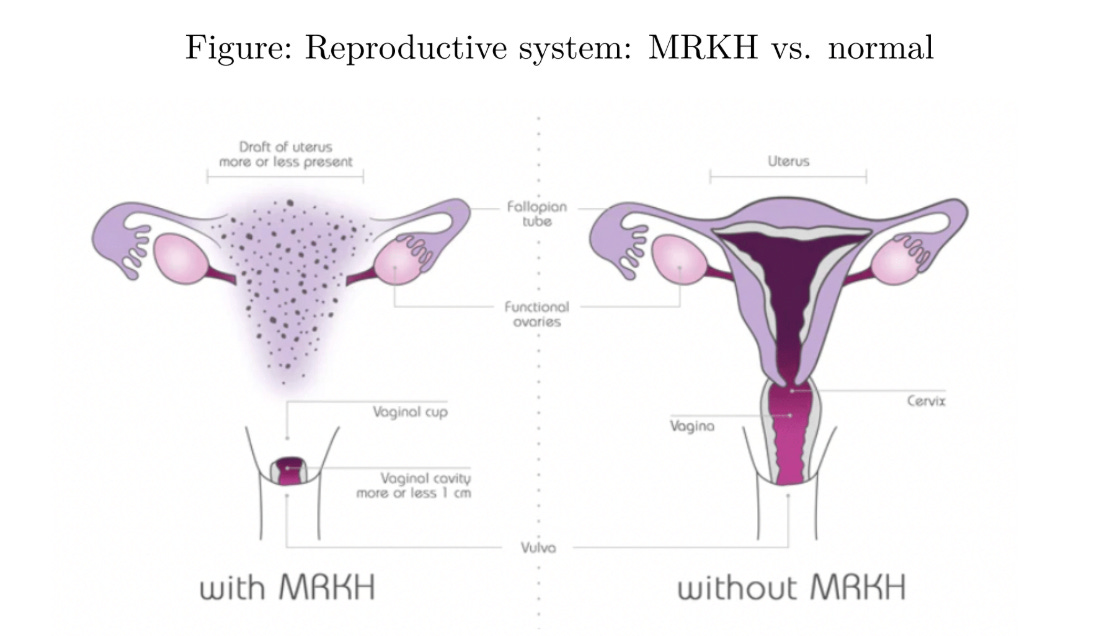

In November 2025, a new, impressively designed study, came out which largely settles the debate. It exploits a remarkably clean natural experiment involving women with MRKH, a rare congenital condition in which girls are born without a uterus but otherwise develop normally. Because these women know from adolescence that they will not bear children, the study can cleanly isolate the causal impact of motherhood itself.

At this point, it’s worth stepping back and asking how we ended up entertaining results that failed the grandma test so spectacularly. The answer lies in the methods themselves: what the IVF papers were trying to do, what they actually did, and why the new MRKH study succeeds where they failed. At a more meta level, why we should have always believed the initial studies.

The motherhood wage gap that isn’t

Claudia Goldin is perhaps the name best associated with shedding light on the importance of motherhood for the gender wage gap, a body of work that she won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2023 for. Goldin demonstrated that the persistent earnings gap between men and women, after accounting for the usual factors, is driven largely by motherhood. Not because mothers suddenly become less capable, and not because employers are uniformly discriminatory, but because modern labor markets reward a very specific kind of time commitment. The highest-paying fields—finance, law, consulting, surgery—do not just pay for skill; they pay for flexibility and availability. They reward the worker who can stay late on short notice, respond to a Sunday-night email, or catch an early-morning flight when needed. These jobs value literal presence: the ability to be responsive and physically present whenever demands arise. Other high-stakes careers like science or intellectual fields rely a lot on accumulated experience. Motherhood often makes this kind of around the clock commitment much harder, and the resulting differences accumulate into a significant wage gap.

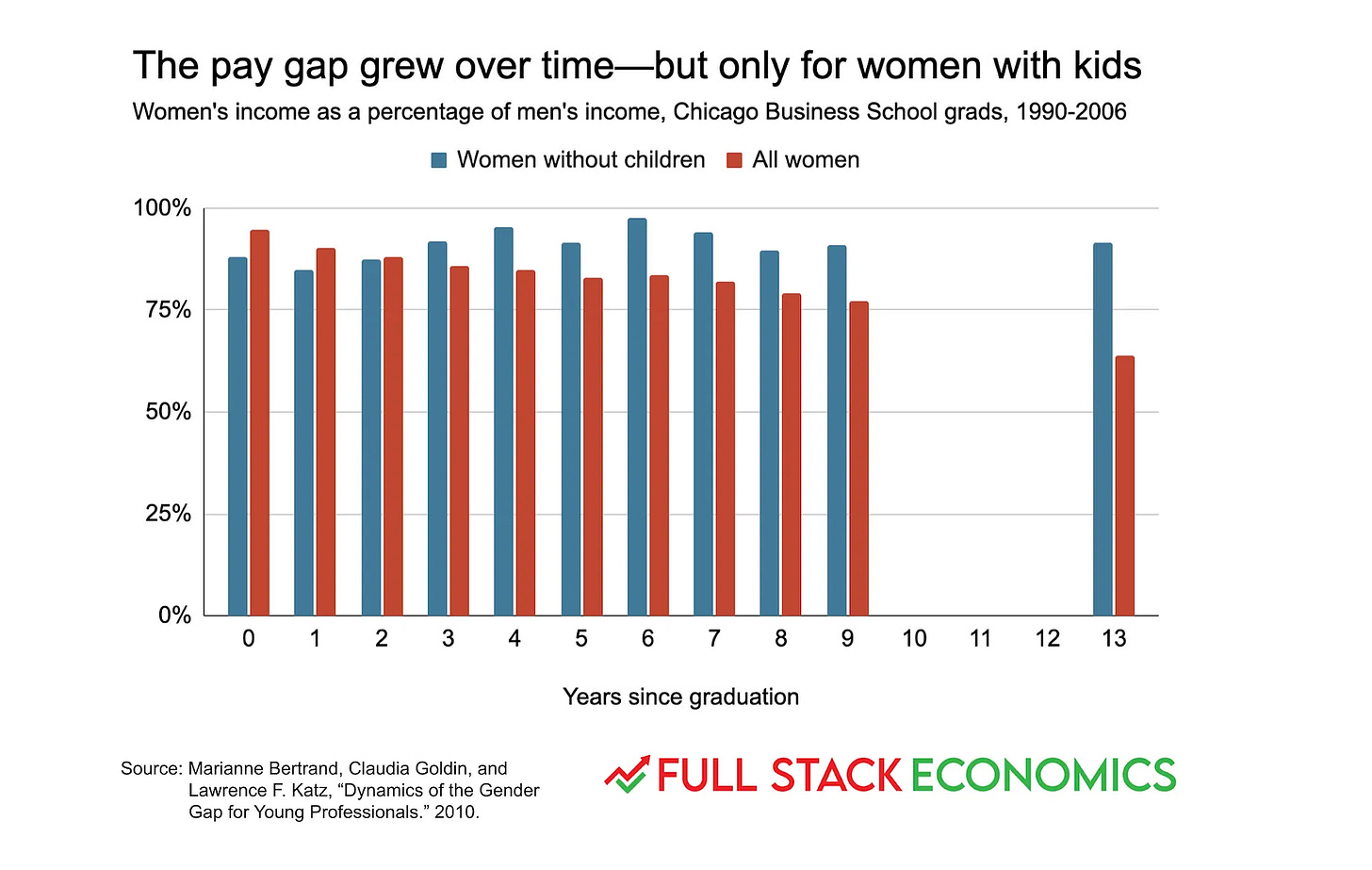

One of Goldin’s pivotal studies examined MBA graduates from the University of Chicago to track how the gender earnings gap unfolds across a career. The researchers found that while women initially earned about 95% of what men earned, this ratio fell to 64% by 10–16 years after graduation, almost entirely due to differences in labor supply. Women with children took more time out of the workforce and worked significantly fewer hours, whereas women without children experienced only a small, stable earnings gap relative to men.

Goldin’s work is meticulously documented and grounded in large, detailed datasets. Her conclusions have since been corroborated by numerous studies across countries and cohorts.

But crucially, her claims also pass the female intuition test. If you have spent time around high-powered professionals, you know how much success depends on stamina, availability, and sustained engagement. And if you have spent time around mothers, you know how time intensive it is. I wholly bought into these results and wrote an article, “Fertility on Demand,” for Works in Progress, arguing that one’s thirties, precisely the years when fertility declines, are also the most crucial years for career progression. This creates a real dilemma for women, who find themselves racing against their biological clock during the most critical decade of their careers. I propose expanding women’s fertility window using technology, to give them greater freedom and soften the harsh trade-offs they currently face.

Yet Goldin’s work, and other similar studies, face an important limitation: they can be confounded by selection effects. Women who do not have children may differ systematically from those who do, perhaps in ambition, career orientation, or other unobserved traits. Goldin and her collaborators carefully chose datasets that allowed her to control for many observable characteristics. Yet even with rich data, some differences, especially those tied to preferences or personality, remain impossible to fully control away.

One way to get around selection effects in economics is to rely on a so-called “natural experiment,” a situation in which luck creates something close to random assignment. One natural experiment researchers thought about is IVF success. IVF success is independent of a woman’s ambition. One can consider women who are all actively trying to have a child and exploit the fact that the success or failure of their first IVF attempt is, conditional on medical factors, essentially random. This allows researchers to form two groups of women who are identical in their intentions, ambitions, fertility preferences, and baseline career trajectories—except that one group happens to have a baby and the other does not. The success of the IVF cycle serves as a so-called instrument: a source of exogenous variation that predicts childbirth but is unrelated to unobserved career-relevant traits. By comparing women who succeed at IVF and those who fail, the studies aim to recover the causal effect of having a child on long-run earnings, labor supply, and career progression, free from the selection problems that plagued earlier observational research.

Methodologically, this approach overcomes the core limitation in Goldin’s datasets: she could control for many observable characteristics but could never fully equalize unobservable factors like ambition or personality.

There are three major papers that use this empirical design. While one finds substantial motherhood-related wage penalties, the other two reach a strikingly different conclusion: once IVF successes are compared to IVF failures, most of the so-called “motherhood wage gap” largely disappears. In effect, these studies argue that women who eventually have children do not suffer major long-term earnings losses relative to the counterfactual in which they remained childless. Instead, they suggest that women who become mothers may, on average, have been less oriented toward high-intensity career trajectories to begin with.

To the objection that women’s earnings are roughly equal to men’s in their twenties and open exactly at the time when they have children, which is strong circumstantial evidence for the motherhood gap, those who buy into the IVF studies also have a response. Early-career work is often about fulfilling structured tasks, whereas true differentiation in ambition and grit becomes more visible in one’s thirties. The fact that this period coincides with motherhood is, according to this view, largely incidental.

Yet these conclusions have always seemed dubious to me and I summarized my objections at the time in a long footnote to my “Fertility on Demand” article.

To begin with, the IVF studies do not even agree with each another: one reports substantial motherhood penalties, while the other two conclude that the penalties almost vanish once you compare IVF “successes” with IVF “failures.” Some of these results hinge on mathematical modelling choices, raising questions about their robustness.

But the deeper problem is actually conceptual. These studies treat “women who fail at IVF” as an appropriate equivalent for women who do not have children. That assumption is extremely fragile. Anyone who has worked with, known, or simply listened to women going through IVF understands that treatment failure is not a neutral outcome. It is an emotionally and physically taxing experience, often unfolding over months or years, that can induce depression, financial strain, and marital conflict. IVF failure can meaningfully alter woman’s labor supply, long-term career choices, and capacity to sustain high-intensity professional engagement. You can discover this by talking to women who have failed IVF. Or, ironically, by reading economics papers who prove these statements quantitatively.

In other words, IVF failure is not a clean “no-child” condition. It is its own outcome, with its own psychological, economic, and temporal burdens. This makes it an imperfect and potentially misleading counterfactual. The shock that is supposed to provide exogenous variation may instead introduce new, unobserved differences that bias the estimates.

A second conceptual flaw is that women make career choices in expectation of having children, choosing more flexible and less well-remunerated career paths in advance. Such an observation should, again, be common-sensical to someone who has lived among humans, but there are actual economics papers that attempt to *prove it*. As a consequence, any design that ignores anticipatory sorting, like the IVF papers, treats endogenous career decisions as if they were exogenous, which they are not.

Finally, the people getting overly enthusiastic about the IVF studies often overlook the nuances in the observational work by Goldin and others, which strongly supports the central importance of motherhood in shaping career trajectories. Goldin, for example, follows the same women in high-powered professions before and after having children and shows that female lawyers routinely drop from working more than 50 hours a week to part-time schedules after childbirth. It’s hard to maintain that someone willing to work 50+ hours per week in her twenties was simply “unambitious”. The data instead suggests women have to make hard trade-offs once children arrive.

No empirical design is perfect. But if I must choose between the Goldin-style design and the IVF natural experiment, I would choose Goldin’s. The natural experiment may appear cleaner on paper, but common sense reveals that it introduces more problems than it removes. This is a case where economists may be congratulating themselves for methodological elegance while drifting further from the truth.

Thankfully, in November we finally got a paper that once again demonstrated that most of the gender wage gap is driven by motherhood. This time, in manner that should be accepted even by someone driven entirely by methodology and without any common sense. The paper uses a very clever natural experiment, as highlighted in the abstract below:

The MRKH natural experiment is particularly powerful because it identifies a group of women who are biologically typical in every respect except one: the congenital absence of a uterus. As a result, they are far less likely to have children unless they pursue surrogacy. Women with MRKH experience normal sexual development and typical levels of female hormones, so the condition should not influence personality, ambition, or other traits that might confound analyses. And unlike repeated IVF failure, which introduces the shocks described above, such as depression and physical strain, MRKH creates a genuinely clean “no-child” condition.

It is important to note that the study has its own caveats. One potential concern is that MRKH might have androgenic effects, such as elevated male hormone levels, that could, in principle, influence personality. I examined this possibility extensively, and the evidence consistently shows that women with MRKH have normal ovarian function and typical female hormone profiles. Nonetheless, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the condition has some other unobserved effect on personality due to biological factors.

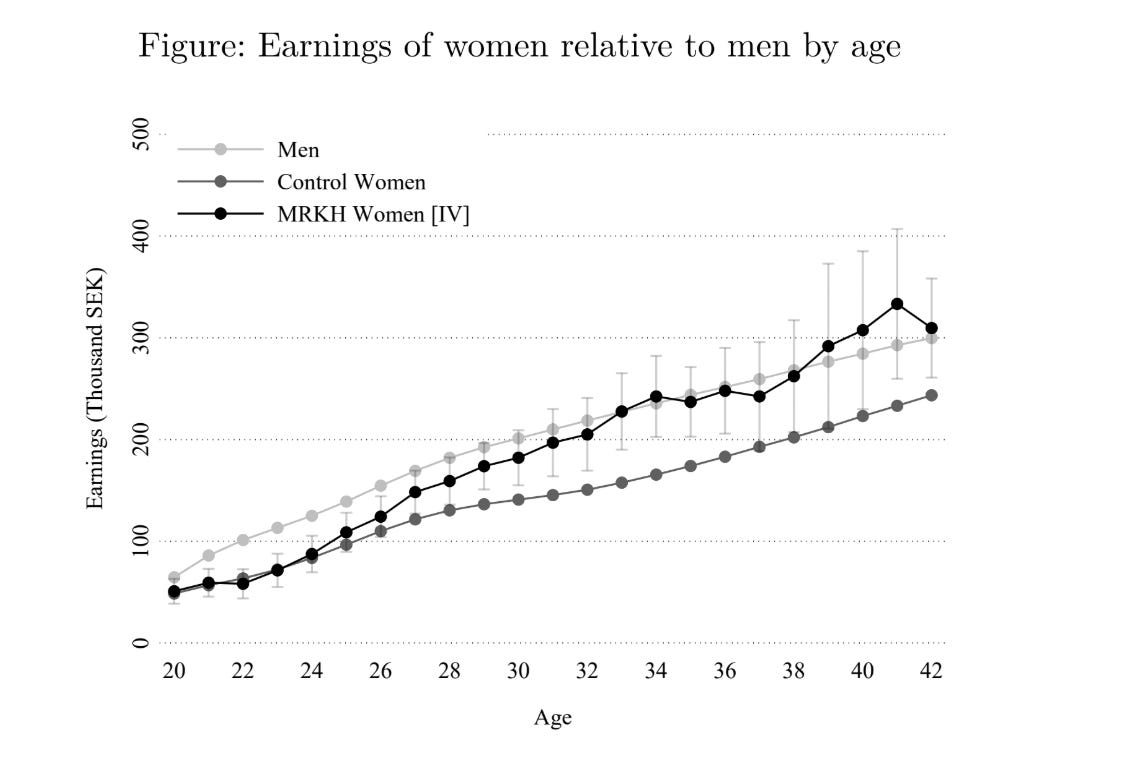

Overall, the results make a strong case that motherhood strongly influences the gender wage gap. The fact that women with MRKH look identical in their earnings to the broader female population, until the moment peers begin having children, and then begin outperforming them dramatically in earnings and employment, offers unusually strong causal evidence that motherhood itself drives most of the gender wage gap. There’s a more subtle point that makes these results unusually convincing. As the plot below shows, women actually earn slightly less than men in their 20s, consistent with employers anticipating future childbearing and discriminating based on that. But over the long term, MRKH women earn the same as men, a finding that directly challenges the idea that women’s lower ambition naturally manifests or compounds with age.

The study also shows that the mere expectation of motherhood shapes choices long before any child is born: MRKH women invest more in education, pursue different partners, and develop more progressive gender attitudes because they understand, from puberty onward, that their adult lives will not be constrained by childcare.

An interesting dimension relates to the “Greater Male Variability” (GMV) hypothesis: the idea that men are overrepresented at both the lower and upper tails of many trait distributions. Because the original study was conducted in Sweden, a country with relatively compressed wages, it would be informative to examine MRKH women in the United States, where income dispersion is larger. If GMV holds, one would expect a gender wage gap in the U.S., driven primarily by the highest-earning men.

Yet it is still striking that no such effect appears in Sweden. Even with Sweden’s wage compression, earnings still follow a Pareto-like distribution, which under GMV should still generate a higher male mean. One important caveat is that the sample includes only 152 women, an unavoidable consequence of MRKH’s rarity. Small samples not only increase noise but can also distort the observed distribution if they restrict variance.

Are women born women?

The recent MRKH study has taken even me by surprise. I had always imagined that motherhood would explain a great deal, perhaps the lion’s share, of the disparities we observe in wages between men and women. Yet I also believed that was not the whole story. Surely, I thought, men’s greater appetite for competition and their keen pursuit of status would have produced differences even in the absence of children.

Simone de Beauvoir, writing at the dawn of the last century, declared, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Her sentence has since become a banner for the most blank-slatist of feminists. I do not belong to that creed. And yet, the study’s findings compel me to revise my estimates in the direction of social construction. It appears that the mere anticipation, the steady, lifelong knowledge, that one might become a mother shapes a person in ways that not trivial. Expectations laid upon us in youth can cast longer shadows than we imagine.

These reflections return me to Camille Paglia’s observation: “There has been no female Shakespeare because there has been no female Jack the Ripper.” She echoes what is the greater male variability hypothesis and, rather ironically, chose literature as her exemplar—perhaps the field least suited to such a demonstration. For while we may safely concede that history has offered no female Einstein or von Neumann, women have actually reached the highest peaks of writing. The collective uncoscious assigned the role of storyteller to a woman, in the form of Scheherazade, who, as Borges said, “saved herself by her stories”. The very first novelist was a woman. And though my own preference for the greatest writer all times lies with Dostoyevsky, I could not fault anyone who places Middlemarch at the zenith of the novel form. If one prefers experiments of style, the contest between Virginia Woolf and James Joyce for mastery of the twentieth century is, to my mind, a matter of taste. And we should not forget that the best-selling novelist of all time is a woman as well.

It is striking, then, that so many of these women who approached or achieved literary greatness did not have children—and, more curiously still, were often celibate. Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, George Eliot herself, Harriet Beecher Stowe: none had children. Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Emily Dickinson, George Eliot, and Harriet Beecher Stowe all belonged to that company. Virginia Woolf’s marriage, by all accounts, was likely unconsummated; George Eliot’s unconventional appearance and the social judgments it invited shaped the course of her romantic life. Even Mary Shelley produced Frankenstein before she became a mother. Perhaps the raw potential for literary brilliance is equally distributed between the sexes; yet the freedom to cultivate it, uninterrupted, unexhausted, untouched by the practical and emotional claims of motherhood, is not.

Still, I would not go so far as to adopt a full blank-slate view. Motherhood exerts its own gravitational pull, but men and women do appear to diverge in certain native inclinations and appetites. What these findings suggest, however, is that the influence of motherhood and even the expectation of it may be deeper and more pervasive than I had allowed myself to believe.

I think you should apply the same skepticism to the MRKH paper that you do to the IVF paper! Three issues off the top of my head. First: per the abstract, MRKH women marry older men, maybe there is a mentoring effect where the older spouses help their younger wives move up professionally. Second, there could be pleiotropic effects from the MRKH syndrome-causing mutations, e.g. altered WNT signaling can drive both MRKH and hyperandrogenism. Third, the paper compares women who know from adolescence they can't have kids to all men. Maybe men who knew from adolescence that they couldn't father children would have the highest income of all, significantly higher than MRKH. You could tell a story like "when you know you won't have kids, you focus on building your legacy in other ways, such as starting a business/becoming an executive/whater". I'm not endorsing those hypotheses, I'm just saying that if one weren't already inclined to agree with the paper, it's easy enough to poke holes in it.

Anyway this is all silly because as you say, it's wildly obvious that children are a big driver of the gender wage gap! I'm not even a grandmother and it's obvious to me! The burden of proof is so incredibly strong on people who disagree with that statement, and even the best social science provides such weak evidence, that there's basically no point studying it!

Very interesting, thank you! I would just add that the MRKH results tell us about the state of the wage gap in Sweden, a country which is quite an outlier in terms of gender attitudes. So while the internal validity is great, I wouldn’t be quick to conclude that the same is true in the US or Japan or Italy