The past was worse: reproductive health edition

In which I tell the sad story of Henry VIII's wives through the perspective of reproductive health and highlight how the entire ordeal would have likely been avoidable with present-day medical tech

Anyone who follows me on twitter knows I’m a techno-optimist & a great appreciator of the Industrial Revolution. I’m particularly excited about the improvements to human health that have happened in the last centuries. Because we have gotten used to these improvements, we have come to take them for granted (yes, I’m a Boomer). I do not have this issue because:

1. I was a very sickly child, for whom medication was a great relief & life saving; so the counterfactual to me is very clear.

2. I read a lot of history and I have a fascination with the medical details involved in the lives of the people I read about. This often cures me of any tendency to complain about the modern world.

I certainly don’t want more people to get sick just so they can imagine what their lives would be without medicine. But I can talk more about 2! Because I think it’s needed among a wave of pessimism about technology and modernity.

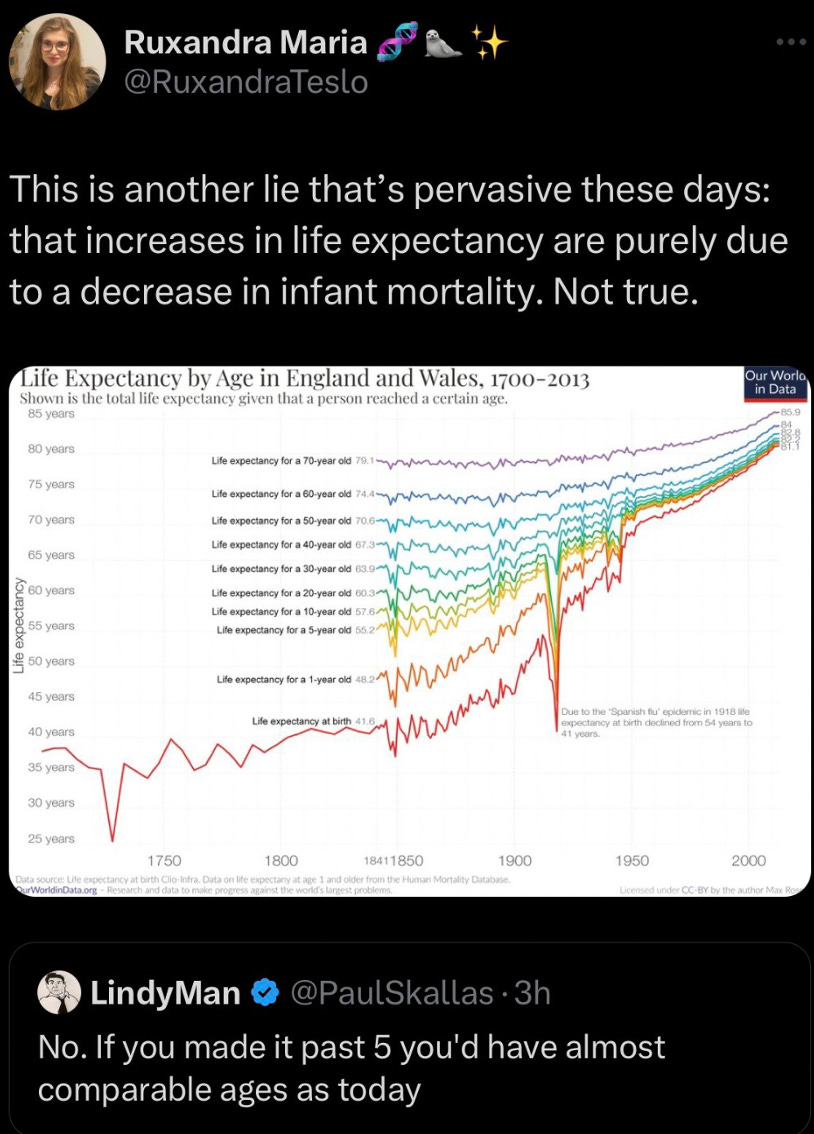

A while ago I tweeted a plot showing how life expectancy has increased significantly in the last 200 years. That’s when LindyMan (& a lot of others) replied: “No, actually life expectancy has not increased that much apart from child mortality”. Of course this is not true. Life expectancy at age of 15 increased as well, as my subsequent post shows. This is one of those discussions that happens regularly between those who oppose modernity and think the Industrial Revolution has been a disaster and defenders of the neoliberal world order like me. But I think there is another dimension to this debate: focusing entirely on lifespan misses the point. It does not do justice to the tremendous impact medical sciences have had in the last couple of centuries. When it comes to health, things used to be much worse, in ways that life expectancy fails to properly capture. Quality of life is unfortunately much less easily quantifiable: we still struggle with it. When it comes to the past, it’s even harder to estimate, so we do not have the same nice & clear plots for it.

I write a lot about current advances in reproductive health and fertility research. But it recently dawned on me this is one of they key areas where we have made big improvements that impact not just lifespan, but also quality of life. And because fertility was relevant socio-politically, it’s one of those areas where an affliction would have had implications beyond the personal and crossed into the political.

The Tudor dynasty is perhaps the best example of the historical impact of reproductive problems. The shortest lived but arguably most famous dynasty in the history of England, it encompassed only 3 generations: Henry VII was the first Tudor; Elizabeth I, his granddaughter, the last one. The dynasty's fertility woes manifested during the reign of Henry VIII, whose quest for a male successor led him to marry six times. His endeavors were complicated by the Church's prohibition of multiple wives, compelling him to find ways to sever ties when a wife failed to bear offspring. His drastic measures included altering England’s religious landscape to annul a marriage, and condemning another wife to death for her inability to provide heirs. Despite his relentless pursuits for a male heir among his six marriages, Henry VIII fathered only three children – two daughters and a son. Yet, the twist of fate lies in the fact that among his progeny, it was his daughter, Elizabeth I, who emerged as the most iconic and influential figure. The Tudor lineage concluded with her, as she remained unmarried, possibly influenced by the tragic fate of her mother.

None of this personal and political tragedy would have happened if the Tudors had the medical innovations we have today. But in an era where infertility was not treatable, and pregnancy was much more perilous, I would consider reproductive health to be one the most important biological determinants of history after infectious disease. Of course, for fertility to have such a big impact beyond the personal, a specific social arrangement had to be in place: that is monogamous marriage. Before delving deeper into the afflictions Henry VIII and his brood suffered from, I am going to discuss the importance of the social institution of monogamy to the topic.

Some historical context

“Too many dragons are as dangerous as too few.”

(George RR Martin - A Feast for Crows)

This quote does not refer to literal dragons. It’s about Targaryens, member of the ruling dynasty in the Song of Ice and Fire book series. I chose it because it captures a truth that applied to the real world for much of the history of modern monarchies. There was a fine line to walk between having too many heirs and too few. And obviously, the type of marriage system would greatly affect which one you’d have to be more worried about: a system that allowed polygamy - too many sons; strict monogamy: too few; If you think I am exxagerating the problem that too many heirs creates, just consider the Ottoman Empire. After ascending the throne, Mehmed II, who ruled from 1444 to 1446 and then from 1451 to 1481, is said to have formalised the practice with a decree that stated "whichever of my sons inherits the sultanate, it behooves him to kill his brothers in the interest of world order." In essence, the Ottoman Empire made fratricide acceptable just to avoid the problem of civil war that too many male heirs often brought.

Western Europe, beginning with the Middle Ages, saw strict enforcement of monogamy. This creates exactly the opposite problem: you might get too few sons. We take monogamy for granted, but even in Europe it had not always been the standard. In the Early Middle Ages, when Germanic customs had not yet been fully “tamed” by the influence of Christianity, a form of polygamy was not uncommon. The Merovingian Kings, rulers of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751, were quite famous for this. Take for example the Merovingian King Clothar, who had seven sons by several wives. Some of these wives were concurrent and 2 were sisters. Clothar’s sons were equally licentious: Chilperic had multiple mistresses, one of them a former slave- Fredegund. After Chilperic married a Visigothic Princess, Fredegund plotted to have his wife killed and became Queen. Another one of Clothar’s sons, Charibert, maintained 4 concurrent wives, 2 of them sisters. For this, he was excommunicated by the Bishop of Paris, Germanus. This shows the Church was already making its power felt. Over time, with the increased power of Christianity, marriage became a much more established and heavily policed institution. No more polygamy or even marrying below one’s status. Even some noble women could be considered too lowly of birth; A former slave was out of the question. This raised the status of the Queen, but also put immense pressure on her to produce heirs. After all, the future of the Kingdom quite literally rested in the reproductive capacity of just one woman. It’s pretty remarkable how strong the social institution of monogamous marriage was, in the face of such a large biological disadvantage. Having many heirs is dangerous, but having none is arguably even worse. And Europe was pretty unique in maintaining such a system: most other cultures allowed a form of concubinage at least when it came to their rulers.

It is true that Kings often had mistresses. In France (where else?) being mistress to the King was actually an official title between the Middle Ages and the 18th century. Agnes Sorel, Diane de Poitiers or Madame de Pompadour famously overshadowed the Queen herself. But their kids were illegitimate and hence not eligible for inheriting the throne. They also had a much more perilous position than the Queen, who was protected by the institution of marriage. Take Diane de Poitiers for example: while King Henri II was alive, she overshadowed the Queen, Catherine de Medici. But the anxiety of being in a position that was fundamentally uncertain can be glimpsed from her behaviour. 19 years older than the King, she took extreme measures to maintain her beauty. After all, losing the favour of Henri II would spell the end of her exceptionally influential position at the Court. When her body was unearthed, researchers found an extremely high concentration of gold, 500 times greater than normal. Her bones were very fragile — unexpectedly so for an athletic woman who swam and rode daily — and her hair was thin and brittle. Both of those are symptoms of gold poisoning. It is believed Diane drank Gold-infused drinks in order to preserve her youth. With hindsight, her worries proved to be unfounded: Henri died before her and all evidence points towards him having been exceptionally loyal to her. But his death impacted her in other ways. Catherine de Medici, now Queen Mother, basically forced her to give up her beloved property, Chenonceaux and retreat from Court.

Henry VIII & Kell Blood antigenicity

"The Queen is ugly and deformed"

This is how An Ambassador describes in 1515, the 30 year old (!) Catherine of Aragon, then Queen of England. Quite a big departure from the descriptions of her youth, when she was unanimously said to be extremely beautiful. But all that seems to had been lost, presumably in some part due to the immense stress (both physical and emotional) that she had been experiencing. Since marrying Henry VIII, Catherine had had 3 stillborn births, 2 of whom boys. Her failure to deliver a son put a strain in her marriage. We know Catherine would not succeed in her task: she would fall pregnant several more times, but all her kids apart from one daughter were stillborn or died soon after birth; We can only imagine the sorrow she must have felt, both due to losing her babies and failing to do her most important duty. The blame was laid on her, as we can tell from a comment by the then King of France Francis I: “My good brother of England has no son because, although young and handsome, he keeps an old and deformed wife”.

Henry VIII's marital saga continued with Anne Boleyn, who captivated him while he was still married to Catherine. They officially married after a contentious and complicated annulment from Catherine. The Catholic Church opposed this annulment, leading him to establish the Church of England; This profoundly altered England's religious landscape for the next centuries. It also greatly intensified already existing political and religious turmoil. Anne had a healthy daughter, Elizabeth, but subsequent pregnancies ended in miscarriages or stillbirths, deepening Henry's desperation for a male successor. The political and personal pressures, combined with Anne's inability to produce a male heir, strained their marriage. Rumours and accusations were thrown around Anne, ultimately leading to her arrest on charges of adultery, incest, and high treason. Despite the dubious nature of these charges, Anne was executed in 1536, marking a brutal end to her relationship with Henry. The chapter following Anne's tragic end saw Jane Seymour entering Henry's life. Unlike his previous marriages, Jane brought the much-desired male heir, Edward VI, fulfilling the quest that drove Henry to break away with the Catholic Church and order the execution of one of his wives. However, the joy was short-lived as Jane died shortly after childbirth in 1537, leaving Henry heartbroken. Edward VI ended up dying young, at 16. Henry would have 3 more marriages, of which all failed to produce another heir.

At the time the blame for failing to produce a healthy son laid squarely on the women, who suffered greatly for it. But the pattern of pregnancy complications across unrelated women arose the suspicion in modern historians that Henry VIII might have been the cause of the issue. More exactly, it has been hypothesised that Henry VIII was positive for the Kell blood group (or K-positive).

So what is the Kell Antigen system?

The Kell antigen system is a group of proteins present on the surface of red blood cells, playing a vital role in human blood transfusions. Individuals either have the Kell antigen (K-positive) or they do not (K-negative). Approximately 90% of the population are K-negative and 10% are K-positive. When a K-negative individual, often a pregnant woman, is exposed to K-positive blood, usually through a transfusion or a pregnancy, her immune system may produce antibodies against Kell antigens, a process known as sensitization. In subsequent pregnancies, if the fetus is K-positive, these antibodies can cross the placenta and attack the baby's red blood cells, potentially causing severe anemia, jaundice, or even fetal death, in a condition known as Hemolytic Disease of the Fetus and Newborn (HDFN). So a K-Positive father (in this case Henry VIII) will cause negative reproductive outcomes for his reproductive partner after the first pregnancy, which is precisely the circumstance experienced with women who had multiple pregnancies by Henry. A K-positive mother will be fine either way, because her body is already prepared to not attack the Kell antigen (otherwise she would die).

I find the reasoning behind this diagnosis quite compelling.

Firstly, it fits with the pattern of pregnancy complications Henry VIII’s wives suffered from. It's tricky to pinpoint the precise number, but estimations suggest that Henry's romantic engagements, spanning across his wives and mistresses, led to a range of 11 to potentially more than 13 pregnancies. Only four of these pregnancies bore healthy children: Mary I, who emerged from Henry's union with his first spouse, Catherine of Aragon, after the unfortunate loss of six siblings during birth or shortly after; Henry FitzRoy, the product of Henry's affair with his youthful mistress Bessie Blount; Elizabeth I, the firstborn of Anne Boleyn who faced multiple miscarriages before her tragic end; and Edward VI, the son of Henry and his third spouse, Jane Seymour, who departed before they could aim for another child. The firstborn trio—Henry FitzRoy, Elizabeth, and Edward—exhibited a K-positive reproductive pattern. Researchers speculate that in certain situations, Kell sensitization might affect even the first pregnancy as seen in Catherine of Aragon's case. Mary's survival might be attributed to her inheriting the recessive Kell gene from Henry and being K-negative (so not being attacked by her mother’s antibodies).

Another piece of evidence comes from looking further up Henry’s ancestral tree in search of the Kell antigen and associated reproductive hurdles. Whitley and Kramer, the authors of the original paper, have hypothesized a connection to Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Henry's maternal great-grandmother. They identify a reproductive disparity among Jacquetta’s male descendants, in contrast to the female descendants who generally had fruitful reproductive journeys (women being K-positive is not a problem for their pregnancies).

How it would look today:

Typically, at about 17-20 weeks gestation, every mother undergoes antenatal blood screening tests that test for the presence of anti-Kell antibodies. If anti-Kell antibodies are detected and are causing anemia in the fetus, in-utero transfusions may be performed to replace the affected red blood cells with Kell negative ones. If HDFN develops despite in-utero interventions, the newborn may require additional treatments post-birth, such as phototherapy to manage jaundice or additional blood transfusions. Pregnancies with K-positive babies are still high-risk. However, studies show that the risk of death can be significantly reduced through timely intervention.

Funnily enough, I have a very similar issue: I am Rh negative. Like the Kell system, the Rh system is one of the blood group systems used to classify blood types, based on the presence or absence of specific antigens on the surface of red blood cells. If I were to have an Rh-positive baby, the same problems K-negative women having K-positive babies would appear. Thankfully, I am born in the right era. And pregnancies which are problematic from an Rh perspective are actually easier to handle than Kell ones!

Conclusion

Although we cannot know for sure if Henry VIII was indeed K-positive, it’s nevertheless likely that whatever caused the multiple miscarriages and stillbirths would be much easier to solve if they had access to the technology of today. The entire saga that led to tremendous personal turmoil for both Henry and his wives, as well as a change in the religion of England, could have been avoided.

The other contributing factor was the strong enforcement of monogamy. Firstborns in K-positive pregnancies are usually fine. If Henry VIII were allowed to have multiple concurrent wives, the chances that some of them would have had a healthy firstborn boy would have been much higher.

"If Henry VIII were allowed to have multiple concurrent wives, the chances that some of them would have had a healthy firstborn boy would have been much higher." I wonder if Henry ever considered changing that rule. Probably not--although he was pretty close to an absolute monarch, it was probably understood that this applied only as long as he operated within a certain traditional framework.