Culture over Policy: The birth rate decline

In which I argue that Culture is often much more powerful than Policy & bring the concrete example of birth rates to argue my case

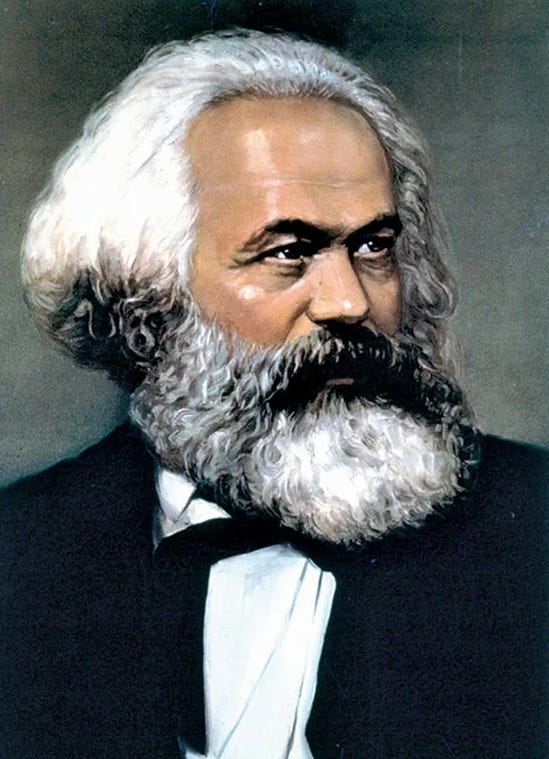

In an earlier post, I discussed my journey out of being what I called a "Culture Incel" - someone who thinks history is driven entirely by material causes and ignores the role of culture and ideas. In many ways Cultural Inceldom maps quite neatly to what is known in philosophy as historical materialism. For me, clinging to this belief was a way to handle feeling out of place within the culture that surrounded me.

But doubts would creep in, and I'd look for something to reassure me: in short I needed to cope. My go-to was an article by Scott Alexander called Society is Fixed, Biology is mutable. In it, he argues that we're better off looking for material or technological solutions to societal problems than trying to engineer society itself. The effectiveness of simple biological fixes, such as lead removal leading to a reduction in crime, challenges the notion that social engineering is the only path to improvement; indeed he argues that Biology is actually much easier to change than Society. His post was written 6 years ago, but it was somewhat prescient: one of the problems he identified as being improperly tackled through social interventions was obesity. In his essay he gives a long list of policy measures that simply have not worked: “labeling foods, banning soda machines from school, banning large sodas from New York, programs in schools to promote healthy eating, doctors chewing people out when they gain weight, the profusion of gyms and Weight Watchers programs”. He floated ideas about changing gut bacteria or cutting out trans-fats as potentially more effective fixes. Jump to 2024, and while he didn't nail the specifics, his general idea that it might be easier to tackle obesity via biological interventions seems correct, thanks to drugs like Ozempic making a splash in fighting obesity. And it's not stopping here: newer and better versions of these drugs are in the pipeline.

At the time, his stance felt like vindication for my Culture Incel mindset, suggesting that attempts at social engineering were doomed to fail. The reason this piece was such good Cope is that it was not even wrong. He was correct about the impotency of policy measures in the face of the mighty forces of Biology. But he was only half right: that is, because he equates “socio-cultural factors” with top-down attempts at social engineering: or, broadly speaking, Policy. And by doing that he was missing the importance of Culture. It speaks to the poverty of my understanding of the world back then that I took that to support my Culture Incel views. I do not think this is an uncommon failure mode: indeed, among “rational”, shape rotator and utilitarian minded people, the kind of people who read SSC, the kind of reasonable writers and policy wonks that avoid the messy world of cultural insanity, this is quite a common view. A good, recent example of this tendency is Melissa Kearney’s latest book on the decline in marriage rates among working class Americans in the last decades. Kearney's analysis appears to overlook the impact of culture entirely, attributing the phenomenon solely to economic changes and proposing policy solutions. Avoiding culture completely does not just make the book factually wrong: it also leads to it suffering from a certain “lack of aesthetics”1, an aspect that a recent reviewer astutely described as:

The conversation around parenting and families and marriage and gender strikes deep in culture war territory, so she deliberately avoids the human narratives that make books emotional and instead sticks with data. The result is that Kearney writes the way I imagine an exhausted surgeon at the end of a long shift would describe the injuries of a dying patient.

The view that Biology and Culture generally trump Policy is probably going to become a mainstay in my pieces. But I’ll use this one to explicitly argue for why Culture (mostly) beats Policy, using one of the most convincing examples: the decline in birth rates observed across developed nations and subsequent efforts to reverse the trend. This adds empirical depth to some theoretical considerations.

Culture over policy: birth rates

Twenty years ago, Finland appeared to have it all. The birth rate was rising and the proportion of women in the labour force was high. Policymakers from around the world, including the UK and east Asia, came to learn about the Nordic model behind it: world class maternity care; generous parental leave; a right to pre-school childcare. But maybe they got it wrong. Despite all the support offered to parents, Finland’s fertility rate has fallen nearly a third since 2010. It is now below the UK’s, where the social safety net is more limited, and only slightly above Italy’s, where traditional gender roles persevere.

This is the beginning paragraph from a recent article in the Financial Times, which discusses the failure of classical pro-family policies to address the fertility crisis. The prognosis is grim: strategies aimed to to maintain a healthy population growth are faltering. Across the Western world (and beyond it), countries are falling way behind the 2.1 target for maintaining a stable population. What’s even worse is that this does not seem to be obviously correlated with policies aimed at supporting parents: it’s not just that we have a problem, we seem to be clueless about how to tackle it. Even countries attempting quite strong pro-family policies (e.g. Hungary) have failed to achieve spectacular results in terms of increasing fertility. On the other hand, there is no obvious policy-level explanation for the European country with the highest birth rate - France. Anna Rotkirch, research director at the Family Federation of Finland’s Population Research Institute, comments on the issue in the same FT piece:

The strange thing with fertility is nobody really knows what’s going on. The policy responses are untried because it’s a new situation. It’s not primarily driven by economics or family policies. It’s something cultural, psychological, biological, cognitive.

What she is saying in that quote is basically: It’s Culture and Biology and their interactions. It bears noting that the idea of social engineering for specific outcomes is a pretty modern one. As pointed out in Seeing like a State, what we call absolutist monarchs were in many ways much less powerful than the modern state. Sure, they enacted taxes and laws and could execute people on a whim, but they lacked both the state capacity and the ideological basis to enforce large scale social engineering tactics specifically looking to change long existing behaviours. The idea that society can be bettered through targeted interventions is in many ways an offshoot of the Enlightenment: the success people saw in taming the forces of Nature gave them confidence that the lives of people could be bettered in a similar way. This is Condorcet writing in 1782 about a utopian vision of a future guided by what we now call Social Sciences, which he envisioned as being very similar in essence to the physical sciences:

Those sciences, created almost in our own days, the object of which is man himself, the direct goal of which is the happiness of man, will enjoy a progress no less sure than that of physical sciences

I am going to leave it to the reader to decide whether the lofty promise of such sciences has been achieved or not.

In particular, the concept of targeted interventions based on quantitative data (what most policy making is supposed to be, at least in theory) is a very modern one. The relative sparsity of statistical knowledge about the population meant that such approaches were largely unfeasible as late as the 19th Century. Yet societies have successfully coordinated before this, so we should a priori expect that Culture is a more successful strategy.

I don’t want to suggest policies & targeted social interventions never work; just that their force pales in the face of the mighty power of Culture and Biology & that they’re hopeless when they go against them. Why might that be? I think it’s pretty clear why Biology is a powerful force and if you do not agree with this simple statement, you might as well stop reading this essay here. What about Culture as an ultimately superior enforcement mechanism compared to Policy?

As Feyerabend puts it in Against Method:

History is full of accidents and conjunctures and curious juxtapositions of events and it demonstrates to us the complexity of human change and the unpredictable character of the ultimate consequences of any given act or decision of men. Are we really to believe that the naive and simple-minded rules which methodologists take as their guide are capable of accounting for such a maze of interactions?

Replace methodologists here with policy makers and you get what I am saying: the ultimate enemy of wanna-be social engineers is the sheer computational complexity of human interactions: the so-called “maze”. Targeted interventions are unlikely to be able to measure and characterise this complexity. By contrast, culture equips each individual citizen with a set of values that they can then enforce upon themselves and others in a myriad of small ways. What these little interactions lack in terms of localised power (compared to the state) they more than make up in terms of adaptability, subtletly, pervasiveness and sheer number. You don’t need a Secret Police if each citizen acts as a small enforcer of norms. And, more importantly, if they do so out of their own volition.

My argument for why Culture works better than Policy is akin to the arguments for free markets over centralised economies. Culture empowers individuals to act on deeply held beliefs, culminating in a force far exceeding the sum of its parts, its impact often elusive until after the fact. Biology, akin to a mighty river, is channelled through the banks of Culture. While we might envisage societal control as the engineering of a great dam, I think in reality it's more akin to casting pebbles into the stream, hoping to alter its course.

Romania: Reversion to the “culture mean”

Some might say that the targeted interventions that have been tried so far in Europe have simply not been strong enough: we do not know how far we can go with policy, because what we have tried so far has been too modest. If only we had an experiment where state intervention to increase birth rates has been maxxed out to ridiculous levels… And it turns out we do!

Communist Romania stands as a stark example, a sort of unintended case study, of what unfolds when a government forcefully intervenes to increase birth rates. In a liberal society, the severity of Romania's methods would be politically unfeasible and deeply morally questionable. The Romanian case study is also useful for this essay because I happen to have lived there for the first 18 years of my life, so I have as good an understanding of its culture as one can.

In 1967, Romania, under Nicolae Ceaușescu's regime, implemented strict policies to increase birth rates as part of a larger strategy to boost the population and workforce. These measures included banning abortion and contraception, imposing a celibacy tax on childless individuals and couples, and conducting regular gynecological examinations on women of childbearing age to ensure pregnancy compliance. Additionally, the state introduced incentives for large families, such as financial benefits and priority in housing allocations. Despite initial upticks in birthrates, the policies eventually led to severe social and health issues, including a rise in the number of orphaned children and a spike in illegal and hazardous abortions that, in extreme cases, resulted in fatalities. An article in the Times captures the dire circumstances women who did not wish to conceive found themselves in, by interviewing the daughter of a Romanian gynaecologist who participated in the abortion underground network:

Get some blood, preferably from a piece of beef, because it is darker. Stain your underwear and smear the blood between your legs. Tell a story: ‘I don’t know what’s happening, I’m bleeding heavily’. He would then give them an abortion at the hospital, claiming that they were already miscarrying and that the procedure would save their life.

If Sigal could not get an answer to all his questions he would send them away, many of them into the hands of “kitchen-table” abortions. Later, in his clinic, he would see the consequences of these procedures: haemorrhages, perforated uteruses and death. “There were many women he wasn’t able to help. He saw them really badly wounded by back-alley abortions, even [some] who died. That was something that I think he had a hard time living with,” his daughter said.

While his tactics lacked subtlety, Sigal remained unscathed thanks to his position in society. He gave abortions to the mistresses of Romania’s secret police, which protected him.

Let’s leave aside these horrific consequences for a moment. Were these policies even successful at achieving their stated aims - increasing birth rates? Initially, very much so. There is an increase in the total fertility rate (TFR) to a staggering 3.5 observed immediately following the implementation of these measures. This uptick is noteworthy when compared to other nations that share similar characteristics but did not adopt equally stringent pro-natal policies. However, women slowly adapted and found ways to prevent conception: throughout the 70s birth rates hovered around 2.5 and went below that in the 80s. But what’s really striking is what happened after the Revolution, when these policies were lifted: birth rates fell to a record low of 1.3 in the 90s. This was concomitant with an enormous rise in abortions: in 1990 pregnancy terminations outnumbered live births 3:1.

I like to call this reversion to the culture mean: once the incredibly forceful measures implemented by the totalitarian regime were lifted, reality started to reflect how much people actually valued large families. The 1.3 TFR perfectly reflects the culture I was born in and know. Romania was and still is to some extent a conservative country by Western standards: divorce, childlessness and, to a lesser extent extramarital sex were frowned upon. I was raised expecting to be a mother one day - that was not the kind of thing to be questioned. BUT, and this is a big BUT, this conservatism did not include large family sizes. In fact, having a large family carries negative connotations. I can only speculate why that might be. Romanians place great value on supporting their children, displaying a less intense focus on early independence compared to what I observed in countries like the UK. This difference is evident in surveys that show a higher average age for moving out of the parental home in Romania. This inclination is likely intensified by the lasting impact of Communist-era hardships, which have ingrained a profound fear of poverty and fostered a compensatory form of materialism. As a result, demonstrations of wealth and a high regard for material possessions are noticeably more prevalent in Romania.

The Communist Regime did try to do some engineering at the level of culture: the 1967 policy reforms included the introduction of a title of so called Heroine Mother, to be bestowed upon women who had given birth to more than five children; but this top down attempt at cultural change never penetrated deep into the public consciousness: in practice, no one considered women with more than 5 children “heroines”. This is very common when social engineers, with no grasp for the subtleties of culture and impatient for immediate results, decide to modulate it: they end up doing risible things that feel completely non-organic. Jesus and his apostles arguably created one of the most powerful and successful social cohesion technologies: Christianity. Yet they did not go around doing “education campaigns” and explicitly telling people how to turn the other cheek with infographics. They inspired their followers with stories; their message was implicit and thus carried more force.

Culture: France’s fertility transition

Just as we have a natural experiment for the policy maximalist position, we also have an experiment for the cultural one. This is demonstrated through a reevaluation of the fundamental reasons behind The Demographic Transition witnessed in developed nations over the past 150 years.

It’s pretty clear there was no concerted Policy effort that led to this transition, so that is out of the window. So far the standard explanation for the Fertility Transition has largely focused on the intersection between unplanned, sweeping changes in economics, mostly downstream of the technological advances stemming from the Industrial Revolution, and their interaction with human psychology (that is Biology). Very broadly, the main argument is that a higher level of development interacts with human psychology in a way that creates strong incentives for reductions in family size. But the influence of cultural factors has been somewhat harder to pin down. Lately, economists have leveraged the fact that the fertility transition happened at different times across different countries to quantitatively evaluate the role of culture — and the findings are quite persuasive.

The perfect case study is France, which saw a decrease in fertility rates earlier than any other country, starting in the eighteenth century, long before the onset of the Industrial Revolution. The contrast between France and other similarly developed countries is striking: as illustrated in the graph below, France's transition to lower fertility rates occurred nearly a century before England's.

A purely materialistic, economic analysis of this difference fails: at the time France was experiencing economic stagnation and the French Revolution had not commenced yet. What was different about France is cultural: it secularised earlier than other European countries. There is strong evidence that religion acts as a fertility “booster”, so the idea that an early secularisation would have led to France experiencing the fertility transition earlier makes sense a priori. And a new paper looking for quantitative evidence for this hypothesis suggests that was actually the case!

The author used crowdsourced genealogical data to estimate fertility in specific geographical locations across France and the presence of “refractory clergy”2 in 1791 in those regions, as a proxy for the degree of secularisation in each region. The effect sizes are quite large: secularised regions in France experienced a significant decline in fertility rates more than a hundred years earlier than their religious counterparts. The estimated marginal impact of the presence of refractory clergy in 1791 on fertility is approximately one. Remarkably, this effect size mirrors the decrease in fertility observed during the latter half of the eighteenth century, where the average number of children born to a woman dropped from 4.5 to 3.5 over a span of around forty years. Another interesting finding is that secularisation seems to have mostly affected fertility at its intensive margin: large families were the most impacted3. To isolate the impact of secularisation from other location-specific institutional factors influencing fertility trends, the study employs several empirical methods. The one that I found most convincing relied on tracking second-generation migrants during the fertility decline and analyzing how the origin district's exposure to refractory clergy affected fertility across generations, despite migration. This approach uncovers a lasting impact of refractory clergy presence on fertility rates that transcends geographical relocation!

This paper is not unique in its conclusions. It adds to a growing body of literature emphasising the importance of culture in mediating economic decisions. I chose it because I did find its results to be among the most striking. Together, these findings add a layer of complexity on top of the purely materialistic understanding of the fertility transition. As economic incentives change, humans decrease the number of kids they have. But culture can greatly modulate the magnitude of this drop: religion and societal pressure stemming from it can greatly boost fertility levels even in economic circumstances that would otherwise be conducive to lower birth rates.

A new fertility transition in the making?

The fall in birth rates we have seen across the developed world in the last couple of centuries has been mostly driven by a steady decrease in the number of families with relatively high numbers of children (3 & 4+). But there is another, more worrying trend that becomes apparent when one digs further into the data: a projected increase in the share of childless adults. This trend cannot be observed directly: childlessness rates are calculated at the end of a cohort’s childbearing years. This means we only have definitive, observable data from women born up to the end of the 70s decade. Among these cohorts, there is no increase in childlessness rates at the end of the reproductive span. So what is there to worry about? Well, for post-1980 cohorts, we do know that early-in-life childlessness has been steadily increasing.

And so far early-in-life childlessness has been a very good predictor of late-in-life childlessness, so one can make some inferences about the future. Applying this logic, demographer Lyman Stone forecasts a precipitous rise in the rate of childlessness among American women born after 1984. For women born in 1992, he projects a childlessness rate of more than 25% at the end of their reproductive span.

This trend isn't exclusive to the United States: in UK for example we see the same increase in the share of young childless women. This phenomenon doesn't come as a shock to me. While economic conditions between developed countries vary to some extent, with the gap between US and Europe that started after the 2008 financial crisis widening, culture in the age of social media is somewhat more uniform.

Such high childlessness rates are not historically uncommon: indeed, as one can see from the plot above, at the end of the 19th century a similar proportion of women never married and had families. But in the past, this was compensated for by the large sizes of families of those who did have children, which explains the overall high TFRs. If Lyman’s analysis holds true, we might be transitioning into an era of both small family sizes AND a relatively high childlessness rate. Of course, one has to bear in mind these are just projections. Many things can happen while women in younger cohorts are still able to bear children: maybe these women will behave completely differently from those in older generations, breaking the assumed correlation between fertility at younger ages and total realised fertility4. Maybe we will see a large cultural shift before these women reach the end of their reproductive span. Or maybe we will dramatically alter reproductive span, allowing women to have children later on in life — the solution I hope for.

These are all reasonable concerns that one can raise when it comes to Lyman’s extrapolation — but there are quite strong indicators that childlessness is being culturally re-enforced at the moment and that a windfall increase in late-in-life fertility among gen Zs and younger Millennials is not really in the cards. As a young woman myself, I do think I am living in a culture that deprioritises having children and, at worst, even regards them with suspicion. To begin, there's a noticeable anti-natalist current weaving through our cultural narrative. A cursory look at popular media headlines—such as those questioning the morality of childbearing in a world grappling with environmental catastrophe—reveals this trend. My time in academia has shown me this isn't just media sensationalism; among the well-educated, there's a consensus that fewer children equates to environmental responsibility, and pro-natalist views are met with skepticism and sometimes even outrage.

Concerns over the environment and strong anti-natalist messages cannot explain everything: one could argue that they are merely a form of virtue signalling and they do not influence actual behaviour much. But there are other, more subtle indicators that people increasingly do not see kids as a fundamental milestone in life. Indeed, as a gen Z woman, I have rarely if ever encountered discussions of children when considering career planning. In one way, I am grateful: I know many coming from traditional societies who have experienced the opposite: an intense pressure to marry, even when such a move would not be ideal for the person in question. But the absolute lack of consideration of children seems equally wrong. What it tells me is that our culture sees children as an afterthought, something to to be considered after career satisfaction has been reached.

This perspective is mirrored by surveys: Pew Research Center reports that only 26% of American adults consider having children as key to a fulfilling life. This is compared to 71% who say the same about a career they enjoy and 61% who regard having close friends as important. The same survey also reveals an increase in the importance placed on having large amounts of money in younger cohorts compared to older ones: while only 13% of 65+ adults believe that having a lot of money is very important for a fulfilling life, as many as 35% of 18-29 year olds do! In another survey from 2024 27% of 18- to 26-year-olds said they saw starting a family as an important goal to achieve in the next five years. By comparison, 72% said they wanted to achieve financial security, and 59% said their goal was improving their health.

These attitudes are not coming out of nowhere, and are most likely re-enforced by older generations. A recent study highlights that many parents place less importance on their children's marital or parental status than on academic and intellectual achievement. This prioritisation of career over family stands in stark contrast with the experience of actual parents, who find time spent with their children deeply meaningful, often much more so that paid work!

Of course, one can find the time spent with one’s children more meaningful in the moment, but still strongly desire to have a good career, due to the sense of security it offers. I also expect that the percentage of people who see their work as rewarding varies a lot by occupation and class, a difference that I believe to be much less true for family time.

Nevertheless, there seems to be a dissonance between what people—particularly the youth—believe will fulfil them (money, career, status) and what they ultimately find most rewarding (spending time with family). How can this seemingly paradoxical situation exist? The explanation lies in considering, once again, Culture and Biology. A culture that exalts career success will naturally lead young adults to prioritise it. Parents, wanting stability and status for their children, nudge them towards societal ideals. Yet biology asserts itself when children arrive, triggering a profound instinct to nurture, hence why parents end up finding children more rewarding. Putting these two pieces together, we get at the final picture: children become a 'guilty pleasure,' indulged in once one has 'earned' it through career and financial success.

Anna Rotkirch's research further underlines this shift: she argues that for many millennials, children are not a foundational aspect of life but a culmination, an accessory to a life already fulfilled. The notion of foregoing childbearing as a sacrifice has reversed; now, the sacrifice lies in forfeiting independence for family. Once you see this, you cannot un-see it. Society instils a deep-seated anxiety about parenthood—the fear of missing some critical preparatory step is pervasive. Having children is no longer portrayed as the default, a hard but ultimately manageable task for most people, but rather as a sort of test, that one can easily fail if not sufficiently prepared for. Tess-Mathilde Bryan, a 22-year-old florist and freelance writer interviewed by Business Insider perfectly encapsulates this attitude in the following quote:

I would just want to make sure that I'm so financially stable and have the perfect place to live, a comfortable place where I think kids would like to be. I feel like people kind of used to just have kids to do it. It used to just be a normal step in people's lives, but I think people hopefully now are taking more things into consideration and trying not to put that expectation on themselves.

In many ways this attitude towards taking the leap and starting a family could be seen as part of a broader “Cultural Anxietying” — a trend towards risk aversion, techno-pessimism and exaggerated caution, that I have flagged a few months ago. That this Anxietying is real keeps getting vindicated in different surveys and polls, despite what the naysayers proclaimed at the time. It’s important to note these attitudes are not coming out of nowhere: they have long been in the making and they reflect in large part the views of intellectual leaders of older generations, now trickling down and becoming mainstream in the younger ones. Consider a paragraph from what is a fairly typical article on what milestones one has to achieve before having kids — written by someone who seems to be a middle aged man:

There are ways to lessen the financial burden you and your future children will face when they reach college age, and the best is preparation. If you make sure you’re in a position to save for your kids’ college education right away, you'll set them up to be ahead of the class—at least financially speaking.

The case for culture's significant role in shaping birth rates is quite persuasive. Anyone examining this issue must acknowledge this straightforward truth, alongside the reality that our present culture is steering us away from the desired path. Lower fertility rates mean less dynamism, less innovation and an unsustainable social security system. Perhaps more crucially, a culture that deprioritises children might misleadingly encourage young adults to voluntarily deprive themselves of something that has been consistently shown to be an important source of meaning in humans’ lives. In the meantime, economists, policy makers and government advisors are arguing how we should rethink policies, calling for radical reforms. However, by overlooking Culture, they risk being entirely misguided, as appears to have been the case for the past several decades. It might be that the fate of birth rates will be determined more by those who shape people’s attitudes, online influencers and the like, than by Government Committees.

Incidentally, this is a problem that plagues many of the “movements” that focus on utilitarianism and policy changes, like EA. But more on that in other pieces.

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy required all clergy to take an oath of allegiance to the secular revolutionary state and made them civil servants. The presence of refractory clergy (those who refused to take the oath) is widely recognized as an indicator of religious devotion around the time of the French Revolution, as highlighted by Tackett et al 1996: “the regional reactions of clergymen in 1791 can be revealing of the attitudes and religious options of the lay population with which the clergymen lived”.

Yes, it's clearly mostly a cultural issue. The costs of having children are obvious, direct, and tangible (money, time, stress, responsibilities, fear of shame and judgment if children don't turn out well, physical transformation and danger for women) while the benefits are often vague and platitudinal ("children are our future," "it's the next step," "it's time to grow up," etc.). Without things like religion to create social and cultural rewards to influence people's behavior, of course people are going to look at those pros and cons above and either have few or no kids. A society can't just make having kids merely more affordable or less strenuous; it has to actively give high status to those who have kids. And you can't just legislate that.

One simple part of this whole thing is that having and raising kids is time consuming and often difficult. Some people naturally enjoy having children more than others, and when the economic imperative to have children is reduced, along with various social/cultural/religious encouragement, fewer people overall will do it, just like fewer people would do any difficult time consuming things if there are fewer incentives / less pressure.

The idea of kids as a capstone rather than foundational is counterproductive for the obvious reason that having kids is way more exhausting when you're older. And I agree that our culture instills utterly insane amounts of fear re: being a parent, motherhood in particular.