Extending women's fertility: the last frontier

Or how to fight the gender wage gap effectively

Scott Alexander has, in my opinion, an underrated essay, written back in 2014: “Society is fixed, biology is mutable” — the idea there is that we are used to thinking that it’s much easier to enact change by altering laws, policies or attempting to “nudge” others to change their behaviour. But in fact, changing Biology itself is, sometimes, easier — see GLP-1 agonists and obesity. This was the starting premise behind the latest piece I published in Works in Progress (WiP): “Fertility on demand.”

In the last century we have made so much progress in terms of women’s emancipation that concepts like the “marriage bar”, where women were forced to resign from teaching positions upon marriage, sound like stories from another world. Yet this was something happening as late as 1944. The conversation has shifted so much, that now we talk about “leaning in”, boardroom seats and pay parity.

But a similar revolution to what has happened in the middle of this century might be on the precipice of happening now. And this time it won’t come from changing laws and policies (although even then, technological innovations like the pill did a lot of work), but, as Scott suggests, from changing biology itself. At the moment, one’s 30s are an important time for career advancement *and* also when women’s fertility starts to decline. This puts women in a race against time. But technological advances that extend women’s fertility windows might give women the option to invest in their careers in their thirties and have children later. A hundred years from now, women having children well into their forties may be as commonplace as married women and mothers in the workforce are today.

Before diving into this, I wanna thank everyone at WiP for doing such an amazing job editing, coming up with suggestions, illustrating the piece and generally being astounding and intelligent and all the good adjectives I do not usually use to describe people. Out of this amazing team, I will single out Ben Southwood, who was my main editor and encouraged me to write the article, after I randomly DMed him about something else, as one does.

This piece serves as a summary/commentary of the economics/social bit. A second, similar piece, but focused more on science part, will follow.

Some thoughts about the current situation

When I met Tyler Cowen in SF a few months ago, he said I am “angry at the right things”. I will forever remember this, because it made me realize it is very much true that most of my writing is motivated at least in part by anger. I almost cannot write when I am completely happy and serene (thankfully that does not happen super often).

And this piece is no different: the seed of anger here comes from having attended various “Women in [insert desirable career]” events in my early undergraduate career at Oxford. Maybe things have changed since then with such events, but back then, inevitably, there was a lot of talk about discrimination, microaggressions, complaining about rude male colleagues and other things like this — all of which are true to some extent. But almost nothing about the real reason why women find it hard to maintain high-powered/ high-status careers in the modern world: children. This is despite the fact that we know that in the Western World, the main reason behind the gender wage gap is motherhood.

Yet relationship and family formation were rarely discussed in such circles. And if they were, the main question was: “why can’t men spend as much time with children as women do?”.

But men *are spending* more time with children than ever before1! However, no matter how much social conditioning one might desire to impose upon the world, the simple reality is that women seem to enjoy raising their own children and that they probably will always, on average, spend more time with them. This is not a bad thing! Children are great and cute and delightful (except for the times when they are not, but that’s another story).

Yet, it is also true that falling behind in one’s career can be extremely frustrating for women who have spent large amounts of time dedicating themselves to building said careers. Because the gender wage gap is more than just about money: it’s about satisfaction and a feeling of accomplishment and enjoyment. It provides many with a sense of meaning and belonging in the world. Furthermore, it is well known that many careers become more interesting and less tedious as one climbs the ladder. And if that never happens, the way one experiences one’s job will be severely affected.

So…. what are we to do? It seems like an unsolvable situation.

Except that it isn’t. Something called “biotechnology” exists. We are not limited to sitting around in focus groups discussing our problems and bemoaning our fates. We, as humans, have the means, more than ever before in history, to alter our biological condition. And that’s what we should attempt to do — expand women’s fertility window so they can choose how to time their careers and childbearing, instead of the current situation they face: a stressful race against time. That technological approaches will succeed is not guaranteed, of course. But only 30 years ago the idea that the life expectancy of people with cystic fibrosis would be 61 (according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation) would have sounded outlandish. Uncertain as it is, science *is* our best shot at helping women take full control of their reproductive destinies.

Greedy careers and one’s 30s

In the book “The Code Breaker”, about the discovery of the famous CRISPR gene editing technology, the author describes how in the last months before their big 2012 publication, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, would work day and night. They were in a competition with another team, from the Broad Institute2, but they ended up being the first to publish the use of the method in a prokaryotic system. With this came the Nobel Prize in Chemistry - incidentally the only one shared by two women. Now, imagine one of them had a small child3 to take care of at the time. Would the late nights and non-stop work have been possible? Maybe, in some cases, with a very supportive partner. But most likely, not.

Doudna and Charpentier work in a so-called “greedy career”: scientific research. These are careers where there is no “set amount” of work you “have to do” because your boss “told you so”. Essentially, the sky is the limit and returns are often Pareto distributed. These also happen to be some of the most prestigious and rewarding careers — and the ones where taking time off for childbearing hurts the most.

From my article:

But the gap does hurt women in ‘greedy careers’ – careers that are greedy for the employee’s time and pay more per hour to the people who work the most. Consider a corporate lawyer working on a deal. The initial hours are spent getting familiar with the material and the people involved. Later hours – once the lawyer understands the case – are much more productive than those at the start. A person working a 40-hour week in this scenario does more than twice as much work as a person working a 20-hour week. Lots of careers are like this.

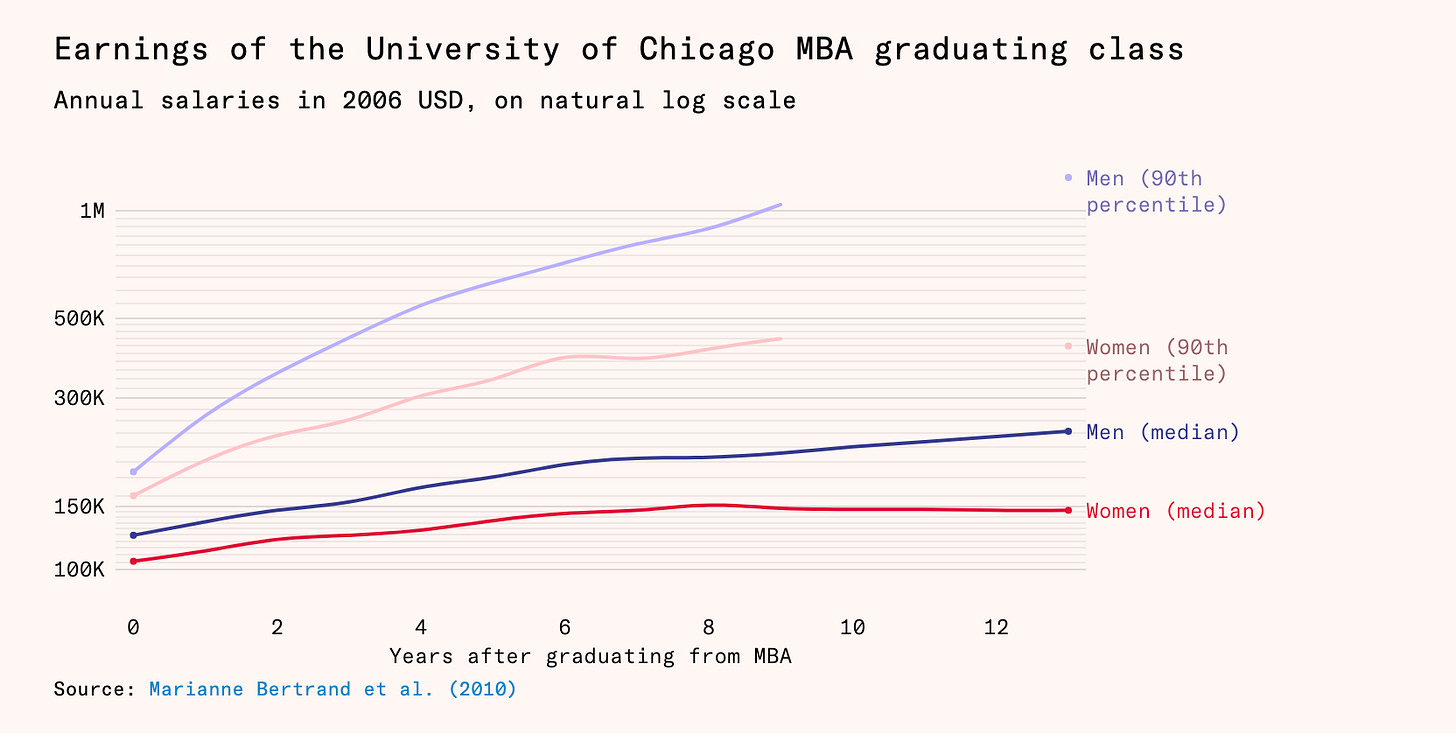

Executives and managers have particularly greedy jobs, and as such, the motherhood career gap is especially pronounced in these roles. One study found that, for their first few years, graduates from the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business (between 1990 and 2006) worked a similar number of hours – around 60. But by nine years after graduation, an hour’s gap opened up. Women working full time worked an average of 52 hours per week, compared with 58 hours for men. They were much more likely to have taken a break from work (32 percent versus 10), be working part time (15 percent versus 3), or to be not working at all (13 percent versus 1). This was reflected in their earnings, which started slightly lower, grew in step with their male counterparts and then, after eight years, began to plateau and fall.

And it’s not just that working long hours matters in greedy careers. The decade when that happens matters too. It seems that one’s 30s are particularly important for job advancement in such greedy careers. One’s 30s is when when young academics go through postdocs and end up establishing their new labs. When lawyers see the highest increases in their salaries. When people who decide to become entrepreneurs have the highest chance of success. And the list goes on.

I have written before about how much I appreciate Katalin Karikó. Being the Weird Nerd that she is, Karikó is, of course, one of the few people that say it is as it is on this topic, too. Whenever she is asked about women in science, she gets straight to the point, instead of the long string of platitudes about bad male colleagues and discrimination and all the other things we are so used to hearing about. In fact, whenever journalists try to subtly goad her in that direction, she makes a point out of saying she never felt looked down upon for being a woman:

I did not feel like my fellow scientists looked down on me. Maybe they said things behind my back which I never heard, but I didn’t care.

Instead, she discusses what’s important: children and motherhood. Katalin Karikó highlights how in Hungary, cheap childcare and a full package of one’s child being “taken care of” more or less by the state, allowed her to return to work almost straight away after giving birth. From one of her interviews:

The thing today is: At the universities, as students, women are sometimes even overrepresented. But after graduation, as soon as they give birth and become mothers, they fall behind and don’t end up in leadership positions. This is also a problem because of the low salary of scientists. If a family does not earn enough to hire a nanny, female scientists will give up their profession. That is a huge loss for the individual person and for society.

As she points out, Science is indeed a truly special career: not only is it greedy, but it is also poorly paid, a combination from Hell in terms of making mothers’ lives truly hard. Pragmatic as always, Karikó has good advice to young female scientists: having a supportive partner that can either pay for a nanny or take on more childcare. It’s truly refreshing to hear someone like her, talking straight and addressing issues in a way that goes beyond fashionable platitudes.

As a note, I think my own stance is a bit less extreme than Karikó’s. I do not want to make it seem like I don’t believe discrimination exists. I have felt at times not being taken seriously for being a woman. Some male colleagues have talked over me and made me feel stupid. I have been hit on (and treated badly upon refusal) in situations where I made it very, very clear that I was interested in professional discussions only. There are certainly “boys only” clubs, especially at the very, very top, that can be hard to access as a woman. And I think as a Weird Nerd Karikó herself might underestimate the importance of networking4 — which is frankly easier to do as a man at the very top of professions (and sometimes when you try to do it as a woman it can get uhm…. weird). This is all true, and it becomes more prominent the higher up one goes and maybe at some point I will write about it. But we have overindexed on this explanation as a society, in my opinion, and underindexed on the motherhood/childcare one. And, to add to this, I am sure men face challenges, too.

Karikó also advises mothers to worry less about sending their children to thousands of extra-curriculars — her daughter, Susan Francia, is a rowing gold medalist (what a family!). Karikó often talks about how she never did anything in particular to provoke this outcome and suggests that it was her strong work ethic and seeing her mother work day and night in the lab, that inspired her daughter to achieve. Karikó believes setting this positive example was more important than having spent countless resources and hours trying to “make her daughter successful”, as many upper middle class parents do these days. Sounds like she would get along with another Weird Nerd, Bryan Caplan, who is very well known for making a similar case.

Anyway, why do one’s 30s matter so much? Some of it might be societal, or the way we set up our institutions. Indeed, Dr. Arpit Gupta made the clever observation that we should do the following things as a society:

early graduation from high school

3 rather than 4 year BA degrees

major in law or medicine up front; rather than in professional school

social shift to promote the young

And I frankly agree! I wish I would have graduated much earlier from high school. I wish I would have started doing research instead of just going to uni courses much earlier. And so on. In fact, if I were to complain about how society “has wronged me as a woman”, it would be that it has treated my limited “fertility time” with extreme disregard. At each step of the way I was encouraged to “be patient”, do more training, told that “things will figure themselves out”, even when I wanted and could have speedrun through things. So I fully support Arpit Gupta’s proposals (which would be good for men too, not just women)!

But there is maybe also a reality that one’s 30s are a sweet spot when one has accumulated enough experience, yet is still quite energetic and mentally flexible.

In any case, whatever the underlying reason, the reality is what it is.

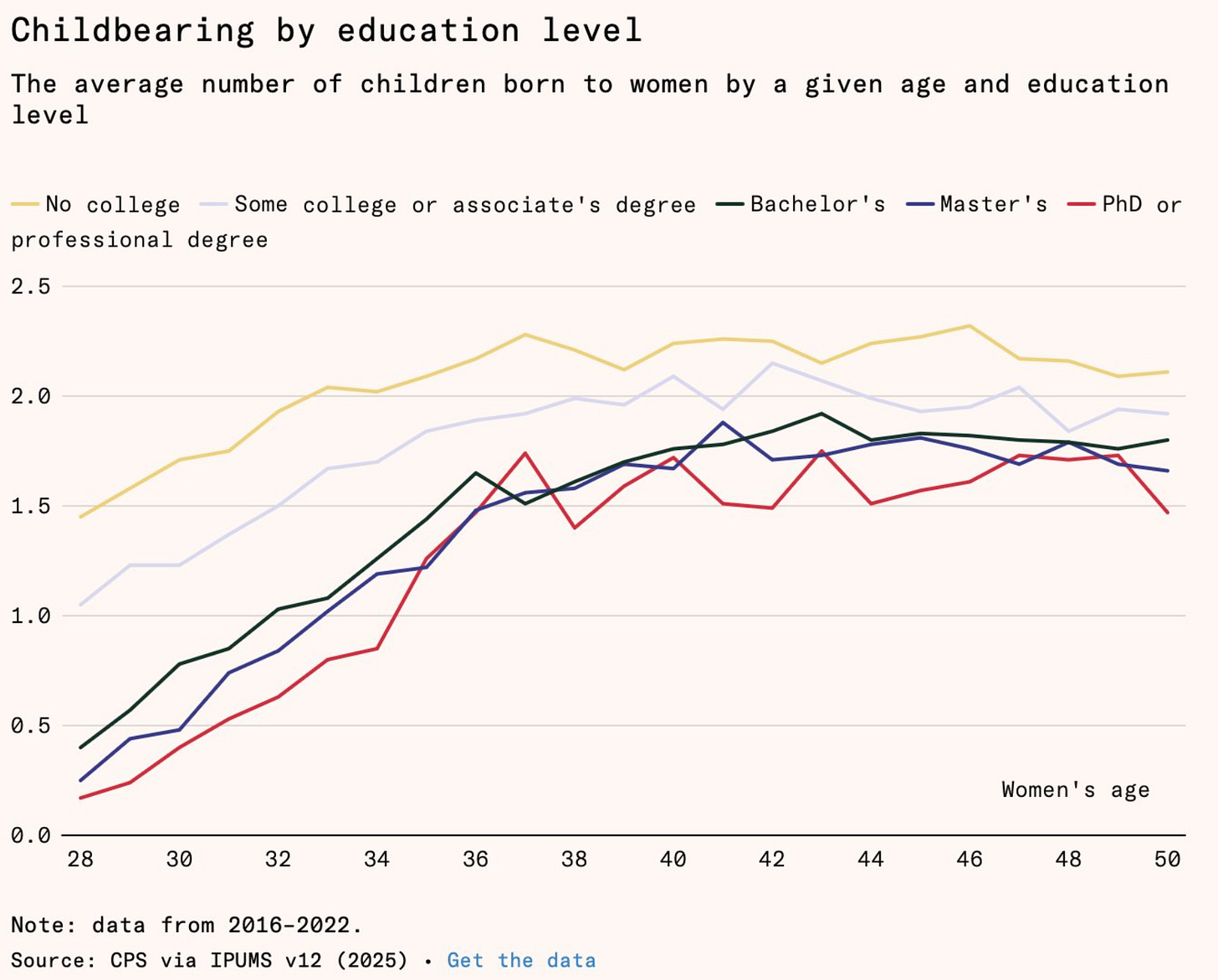

Women know this is how the job market works and act accordingly. As the plot below shows, they often postpone starting a family until they've made significant career progress—a trend especially noticeable among those with PhDs or professional degrees. For example, by age 28, women without a bachelor’s degree typically have between one and one and a half children, while those with higher education average only about 0.25 children. Although highly educated women tend to accelerate childbearing in their thirties to make up for earlier delays, overall fertility rates tend to level off around age 39, resulting in fewer children on average for this group despite their efforts to catch up. This is because, no matter how much the highly educated group wants to catch up, biology gets in the way. I am not going to rehash here the decline in fertility with age — it’s all detailed in the article.

I want to stress at this point, that even if you do not care at all about women’s careers, this is a loss at a societal level. Educated women want more children and they do not end up having them. Unless one really buys into trad fantasies, it’s hard to believe ambitious women will give up entirely on their careers en masse anytime soon. So helping them achieve their fertility goals should be enough of a reason to support expanding their fertility window, even if one does not care at all about their career progression and satisfaction5!

Claudia Goldin’s solution

I mentioned before that my writing is often motivated, at least slightly, by anger and that Tyler made me realize this.

I was also a bit angry at the conclusion from 2023 Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin’s book “Career and Family” — an otherwise excellent piece of work that lays out in depth how women’s progression in greedy careers is affected by motherhood. She gives the example of the pharmacist profession — one that used to be greedy but now, because of tech advancements and automation, is much more family friendly and has a small gender gap, yet is still a respectable and well-remunerated career path.

But — without wanting to insult any pharmacist, it also sounds like a career that has been hollowed out of its creativity and “spark”. The truth is, the very things that make careers greedy, often correlate with what makes them original, interesting, meaningful. Those hours at night spent reading papers? It’s because you are working in a fast-paced field, that you can barely keep up with during a regular 8 hour schedule.

Pharmacists used to formulate medicines on a person-by-person basis and to have much more authority. Now, their role is much more limited and seemingly less creative. Her solution is to basically turn more of the greedy careers into something resembling pharmacy. That seems not only impossible (how can you make being a CEO less “greedy”?) but also… undesirable? It’s a solution that looks good on paper (yay women earn well in this profession and also kinda the same as men!), but not in practice. Is the work interesting? Is it at the forefront of innovation? Meaning in one’s career does not come from comparing one’s salary to their male’s colleagues’ salary and being satisfied it’s the same… Meaning comes from having the time and space to dedicate yourself to your work, truly and exhaustively.

Does the motherhood gap even exist?

Some studies have challenged the magnitude of the motherhood wage gap. For example, a recent paper compares the trajectories of women who have children with IVF versus those for whom IVF fails – as a ‘natural experiment’ for the impact of motherhood – and shows that the long-term difference between them is small (much smaller than the motherhood penalties that people usually reference). However, this research suffers from several limitations.

These studies have gained a lot of traction, especially on twitter. Sometimes I wonder if people who really believe these studies understand what being a mother really entails and how much it clashes with greedy careers. However, appeals to common sense are clearly not enough, so I will give some more “data-driven”, science supported arguments. Furthermore, I really recommend getting familiar with 2023 Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin’s body of work, because she focuses a lot on “greedy careers” and has a lot of very good studies. A good start is her book “Career and Family”.

First, we know that the IVF process itself is highly disruptive – in the UK as many as 15 percent of women who go through it reduce hours or quit work altogether to cope with its demands and 40 percent report having suicidal thoughts while undergoing fertility treatment. I personally know women undergoing IVF for infertility — their careers have been affected by the process itself.

Second, failing IVF is strongly associated with mental health issues, which we should reasonably expect to have a negative impact on productivity. Indeed, a recent study looking at the impact of IVF failure on labor market outcomes finds that involuntarily childless women are a staggering 48 percent more likely to suffer from mental health issues several years after facing infertility. The same paper shows that the impact of infertility on wages negates any gains a woman would get from not having a child, presumably due the aforementioned association with poor mental health.

Third, women who fail IVF are probably less physically healthy than the women who succeed, meaning they aren’t direct comparisons.

Fourth, there is evidence that women sort into more flexible and less well-paid careers in expectation of having a child, which they would presumably also do prior to undergoing IVF. Having a child is not something women suddenly fall into. They plan ahead. They choose less well remunerated medical specialties due to work flexibility. They avoid certain career paths to begin with.

All in all, women who fail IVF are simply not a good control group for “simply not having children because one does not desire to do so”.

And there is one last point: these IVF studies do not look specifically at greedy careers, which depend much more on compounding gains in one’s thirties. I think I have done it already, but I would like to stress again how different greedy careers are from regular jobs. Missing a key point in a greedy career can be an irreversible event. That first tenure track job. That first good grant. A good book deal. Being made partner. In Science, there are prestigious fellowship that are given specifically to those that are within X years of having finished their PhD.

This is a generalized cultural thing: those in competitive fields look very, very differently on someone if they are attempting to do all the things mentioned above in one’s 40s rather than one’s 30s. There are jokes about the “ageism” of Silicon Valley, where one is considered a failure if they have not founded a company by their mid 20s. They are exaggerations, of course, but they contain more than a grain of truth. An expectation of precociousness and little patience for those who want to catch up in their 40s is a common theme in most prestigious careers. And that is something IVF studies in Denmark, on women in public sector jobs, won’t be able to capture.

Will we ever achieve “complete equality”?

Frankly, and this might come as a surprise to those reading this piece, I do not really care. I suspect a number of factors, including men being more driven by status, or generally choosing remuneration over “meaning”, means we might always have a gender wage gap.

However, what I do care about is that the women who want to pursue difficult, greedy careers (which include careers that are not that well paid, like academia), can do so, without feeling like they are in a race against time. If that is achieved, I frankly do not care that much if the gender ratio in high frequency trading is 25/75 or 50/50 or whatever. I want choice and freedom for women, not ticking boxes on paper (which is my problem with Claudia Goldin’s solution). Really, the gender wage gap and its relationship with motherhood is just a springboard for me to argue for this type of freedom to pursue one’s ambitions, whatever those might be. I am not a “gender wage equalizer” fanatic or anything like that. A free society will lead to differences in outcomes between people and that’s fine!

But when those differences arise from heartbreaking choices, like whether to pursue one’s dream career or to make sure one is not aging out of their fertility window, that to me seems like a problem to be solved. Enough said now about the social and economic aspects… the second part will be about the Science of how to make fertility extension possible.

And women spend even more.

There’s an entire scientific drama around this and patents and much more. I recommend reading the entire book for a better glimpse into how science really works. In the end, Doudna and Charpentier won the Nobel Prize, but the Broad Institute team won the patent battle.

Charpentier does not have children, while Doudna’s boy was a teen a time. Not a great time, but certainly not as demanding as a young baby.

To spell this out, at the very top of many professions, networking is key. You start a company with that pal you played tennis with. Women are severely disadvantaged here. Because a) they have slightly different interests b) you think you network but the guy is hitting on you c) men might genuinely take you less seriously. It is a thing at the very top. At the same time, I do not think it is the *main thing*. Writing on the internet is a place where one can avoid these pitfalls, because there is no in person interaction. Maybe that guy thinks you’re interested in him and you are not. So what?

Of course, this is assuming one is merely “trad” and not a misanthrope who simply does not care about either women’s careers or the world at large.

As a biotechnologist, I'm not at all averse in principle to use modern medicine to increase the fertility window, but I think that this solution misses many important drawbacks.

For starter, the fact that parenthood is extremely physical as a job, especially. In the first years. That energy and mental acuity, as well as greater physical strength, that one has in 20s and 30s is really important when raising children. My first daughter was born on my 36th year, the second on my 39th, and while I keep ok-fit... it's hard. Waking up at night, lifting them, being mentally alert, these are things that I feel already ever so worse at now that I'm 39; I do not want to imagine having to do them at 49! Enabling people to have children later does not solve this problem, and many technological solutions that can help (prams, screens, etc) are actually bad for children if overused. As one would as a tired parent.

Modifying society is harder, but potentially much better in terms of end results.

Good essay. I agree with some key aspects of your framing about greedy jobs and rewarding work, and If we could technologically facilitate advanced-maternal-age pregnancies without popularizing them, that would be ideal. Unfortunately, if culture is as intertial as you suggest, innovation enabling later pregnancies will beget even more extreme delaying, and women needing to postpone childbirth into their 40s to protect any shot at securing high-status and meaningful work sounds nightmarish (and potentially deadly, if it entails a surge in maternal mortality rates).

Many of society's current maladies can be ascribed to the overbearing credentialist arms race for high-quality careers pushing back life milestones too far, and the only backstop preventing further slippage is the biological ceiling on fertility; once this is circumvented, the contest for high-end positions will extend the meritocratic/educational prelude to elite careers another ten years or whatever, and our situation will further deteriorate. We have good reasons to shorten the on-ramp to meaningful work; proliferation of more advanced fertility-window-altering tech will culminate in elongating that on-ramp instead.

(I have an essay inveighing against subsidies for egg freezing that explores this stuff in greater detail if anyone is interested: https://unboxedthoughts.substack.com/p/feminisms-refusal-to-save-humanity)