Female neediness is real, but it's not a tragedy

In which I discuss the greater female need for commitment, the absurdity of anti-freedom "solutions" to it (coming from reactionary feminists) & argue the only thing that can help is a better Culture

“It's you, it's you, it's all for you, everything I do

I tell you all the time, Heaven is a place on Earth with you

Tell me all the things you wanna do

I heard that you like the bad girls, honey, is that true?”

(Lana del Rey- Video Games)

In 2012 Lana del Rey rose to prominence with her single “Video Games” - a melancholic ballad about unrequited love, which captures the longing and devotion of a woman to a man who is indifferent to her affection, focusing instead on playing video games. Since then, she has cemented her place as the foremost voice of “female neediness” - releasing album after album for the last 11 years. To my boyfriend, her songs sound all the same and like “whining”; to me, they are all meaningful and very much distinct. That she jumped to such prominence in an era where the dominant narrative was one of almost cartoonish girlbossiness is not random in my mind: she gave a voice to that which was unspoken.

What is this “female neediness”, then? It’s a term recently used by Stella Tsantekidou in her latest post, “The Desperation of Female Neediness” to describe the greater desire for romance and commitment that young women feel relative to young men.

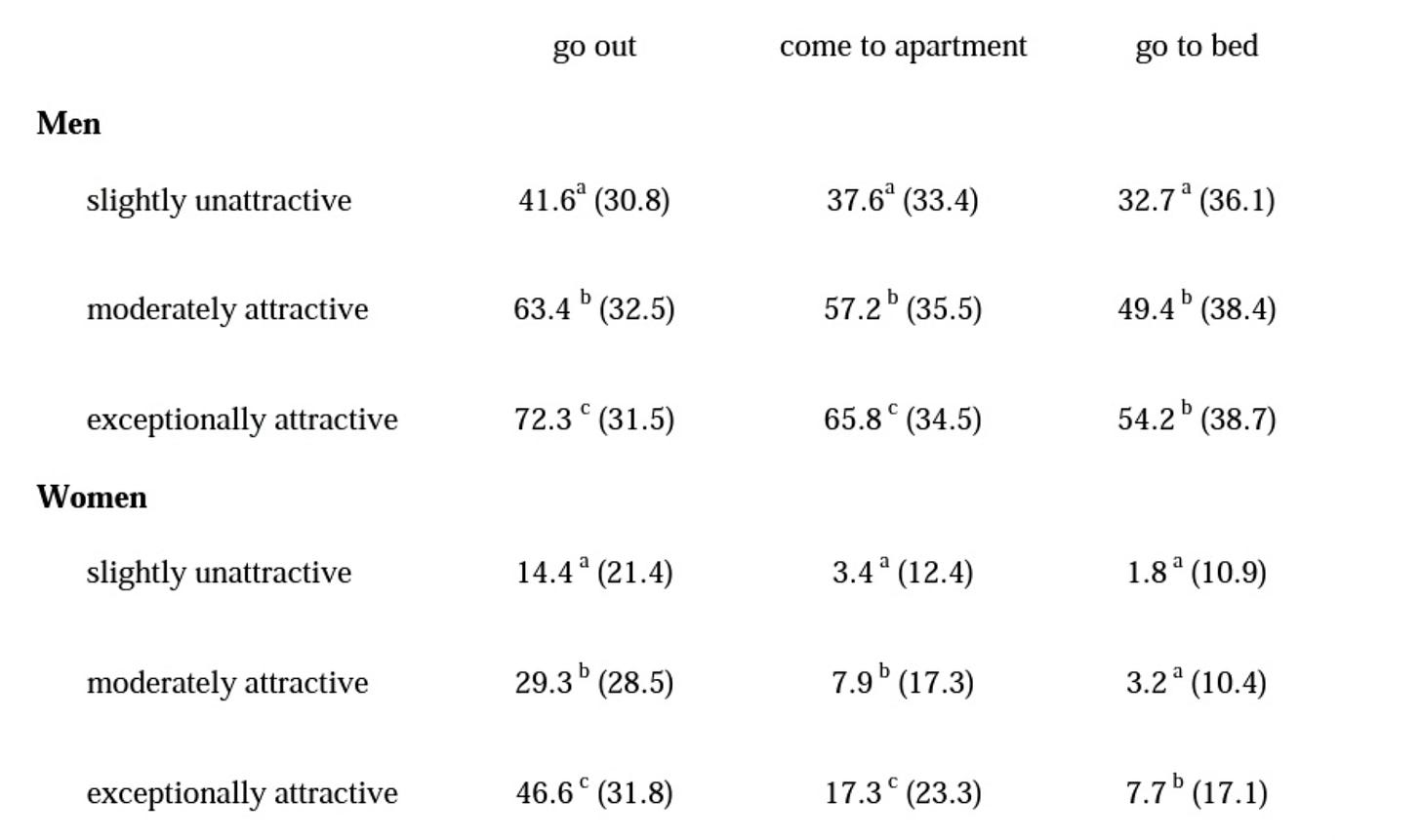

When one looks at what men and women want in love, a clear difference emerges. Surveys show that women generally aren't as interested in casual sex as men. It's not that men don't want something serious—they can and do fall in love. But they're also more likely to be okay with casual hookups along the way. Women, however, seem to have a clearer focus on finding a committed partnership1. And it’s not just that they are less interested in casual flings; they also tend to regret them more afterwards. This doesn't mean men are against being in a committed relationship or that women never enjoy casual sex. It's just that on average men have a more flexible approach, being open to both serious relationships and casual sex - and obviously in the illegible and complicated world of romance the difference in priorities will inevitably create some friction.

Everything I said above should come as no surprise to anyone who has touched grass in any meaningful way in their adult life. But this is not a topic that’s often talked about explicitly, at least not in educated gen Z circles- there’s almost shame in admitting the reality. Why? I do not know - I don’t find any of this particularly shameful for anyone involved, and especially not for women2. Emblematic of the way we talk about these issues is prominent feminist Kate Manne’s own approach. In a recent article, she describes her experience of feeling empty after engaging in casual sexual sex during her youth.

And so I entered a period during my college years of needy and sometimes risky promiscuity. I went out to nightclubs and raves. I took up smoking to allay my social anxiety and to have something to do with my hands there. I reverted to not eating for days at a time, losing a significant amount of weight in the process. (I gained it back soon afterward.) Partly to aid my dieting, I took party drugs like speed and ecstasy. I drank more than I could handle. And I slept with more or less any conventionally attractive man who approached me. These behaviors, while not necessarily problems in themselves, made me feel empty, anxious, and depressed, given my natural proclivities for order, comfort, and safety. Most important, they put me at risk and made me vulnerable to sexual predation.

Surprisingly, given that her piece is quite long, she manages to blame her lack of satisfaction with the meaningless hook-ups of her youth on everything under the sun: misogyny, fatphobia, male privilege etc, while conspicuously avoiding any mention of the gap in preferences for casual sex between men and women. I believe this reluctance to address the topic heads-on has several negative consequences. Firstly, it creates unnecessary confusion among young women in particular, who often don’t really know why they feel what they feel and how to protect themselves from potential heartbreak. The best analogy to this is Victorian prudishness around sex itself, which left many women bewildered by their first sexual encounter, and even ashamed of enjoying sex altogether. Instead of some much needed clarity based on empirical data, “Patriarchy” and “Misogyny” get invoked like miasmas were in medieval times: these vague things that float in the air and make women unhappy, mostly at the hands of men. This way of addressing the topic also serves to increase animosity between the sexes & anxiety among young women regarding encounters with men, on the background of an already quite gender polarised youth. I believe demystifying the whole thing, making it clear that it’s down to differences that are neither inherently bad nor good, would strip away from the tragedy of it all. No one is at fault for this: men are not evil, women are not difficult. It’s just a fact that happens to be true, and knowing it is another tool in the personal arsenal with which one can now confront reality.

The Backlash

When I release this piece, I am sure some people will scream at me: “But this is not a taboo Ruxandra, everyone knows this!”. Well, it’s rather weird, because the only place where I’ve found this stuff discussed heads on is on Substack. And there seems to be a real appetite for such discussions, judging from how much engagement Stella Tsantekidou’s latest post, “The Desperation of Female Neediness” got. Her piece is rather dramatic (as you might guess from the title, which includes the word “desperation”) and focuses almost entirely on the negative facets of being a young city dwelling and otherwise successful woman, who nevertheless seems to not be able to get past the casual sex stage and find a long term relationship. I believe Regan Arntz-Gray has a good rebuttal to the piece, in which she brings up the fact that finding a committed relationship is not actually that hard for women, and it’s usually the very high standards they set —the need for status in the men they date— that make it so:

But, when they’ve been looking and actively wanting a committed relationship… they’ve generally found one within ~6 months. Not to rub salt in the wound here, but I’ve seen more girlfriends struggle with the concern that they’re jumping into a new relationship too quickly after the previous one dissolved than I’ve seen struggling to replace an ex.

Regan is right in important ways, but there’s a reason why Stella’s piece got so much attention. Given differences in what women and men often look for, experiencing heartbreak at the hands of a heartless fuckboy, or even a fundamentally good man that might simply not return one’s feelings, is in the cards for most women. To some extent that’s tied to the female “desire for status” as Regan calls it, but I believe it’s more than that. You can fall in love with a man that’s in theory in the same league as you, who simply does not love you back with the same intensity for a myriad of reasons, yet will still gladly get involved in some casual sex.

It’s evident that people do find this topic interesting and want to talk about it because it affects our lives in meaningful ways. But the lack of respectable explanations for this situation has created a void that reactionary voices have been more than eager to fill. Among these are the "Reactionary Feminists," a relatively heterogenous group advocating for a return to traditional values and criticising the Sexual Revolution. In a recent essay, Astral Codex Ten argues that our attitude to love, with its adherence to freedom amidst inherent unfairness and risk, embodies libertarian values in a world increasingly devoid of such freedoms, making it a unique and vital realm where individual choice and adventure still prevail.

Well, reactionary feminists want to take the choice from love too. So far they sound like traditional conservatives - one might wonder at this point why they even call themselves “feminists”. And the reason is that they think such a return would fundamentally benefit women the most. For the most part, I find their arguments and solutions as detached from reality as those coming from the Patriarchy-Miasma people, but it’s worth addressing them nevertheless.

Perhaps the best known reactionary feminist is Mary Harrington, who wrote an entire book titled “Feminism Against Progress”- the gist of which is that Post-Enlightenment developments —on societal, moral and technological fronts— have been much worse for women than commonly accepted. One of her biggest obsessions (after boners) is the contraceptive pill and how much harm it has caused women. When I watch a video by Mary Harrington in which she mentions the pill (and she does do it a lot), it usually goes like this: she would start with the concern over the medical side-effects of the pill - an important and reasonable concern! But it does not take long until it becomes quite obvious she is more fundamentally against the idea of contraception itself. Why, one might ask? To quote Mary herself:

Uncoupling sex from reproduction opened the door to the privatisation of bodies.

I think this sentence pretty much summarises the core of her ideology and much of reactionary feminism itself: she believes that the progress we have witnessed in the last centuries, the apotheosis of which is “the Pill”, has somehow commoditised women. Before this, they were valued as people; now they are merely numbers in the long list of casual liaisons of soulless fuckboys. The problem with her analysis is that it’s mostly ahistorical and ignorant of human nature — which is quite ironic given how much she criticises progressive feminists of doing the same things. For as long as humans have organised themselves into societies, there has been a “commodification” aspect to human interactions: that is, humans have been assessed according to their status as well as the benefit they could provide others by associating with them; that people might want to get something from you that might not always be in your interest (in this case, casual sex) is not a feature of modern feminism: it’s a fundamental aspect of human nature. And women in particular have been treated as property throughout history, especially in relation to their sexuality and particularly because sex was tied to reproduction. To make my case going forward, I’m going to ignore the many ways in which past norms prevented women from engaging with the public sphere. I personally think these are important, but for the sake of argument, I will focus on the sphere that reactionary feminists claim has been the most damaged by liberalism and the one they care about: the private sphere.

The commodification of women was the historical norm

The women Davis surveyed repeatedly made clear that they had entered into marriage with the expectation that their husbands had the right to control the terms of marital intercourse, although they were hardly enthusiastic about that husbandly prerogative. When asked whether they had been "'adequately prepared by instruction for the sex side of marriage," a number of women reported that their mothers had explicitly conveyed this information about the nature of marriage to them. As one wife in this cohort explained, "'My mother taught me what to expect. The necessity of yielding to her husband's demands had been a great cross in her own life.

This passage, from Contest and Consent: A Legal History of Marital Rape, summarises some findings from Katharine Davis’ Factors in the Sex Life of Twenty-Two Hundred Women. Published in 1929, this was one of the earliest systematic surveys of female sexuality. That women were used for sexual pleasure at a husband’s discretion and were considered to owe him sex, whether they enjoyed it or not, should come to no surprise to anyone familiar with the topic (e.g. from reading biographies written by women of that era). Yet it is still somewhat striking and unnerving to a modern reader to think of marital sex as “a cross” a woman has to bear. These personal accounts match legal history: marital rape was not criminalised until the 20th century, with some countries being surprisingly late to it. In US, the court case Oregon v. Rideout in 1978 was the first case in which someone stood trial for raping his spouse while they lived together.

The earliest written legal source on marital rape appeared in a 1736 treatise called “History of the Pleas of the Crown” by Sir Matthew Hale, a former Chief Justice of the Court of King's Bench in England. Hale stated:

The husband of a woman cannot himself be guilty of an actual rape upon his wife, on account of the matrimonial consent which she has given, and which she cannot retract.

This became known as the marital rape exemption. This exemption provided a normative structure of marriage in which permanent sexual access was a constitutive part. As Law Professor Jill Elaine Hasday puts it, throughout the 19th century:

Rape laws stated what a male person could not do to any woman, other than his wife. Legal writers took pains to emphasize that [a] man cannot be guilty of a rape upon his own wife, that "a husband does not become guilty of rape by forcing his wife to his own embraces," that rape "may be committed by any male of the age of fourteen or over, not the husband of the female." This clear prohibition on prosecution had its intended effect.

Such accounts clearly establish women as property of their husbands, their sexual and personal satisfaction as secondary concerns. The extent to which women were seen as mere commodities can also be glimpsed from attitudes towards adultery on the part of the wife: it was mostly regarded as an affront by a man to another man’s property. If a wife had extramarital relations (against her husband's wishes), the common law permitted the husband to collect civil damages from the other man, financially compensating him for "the invasion of his exclusive right to marital intercourse with his wife”.

Another obsession of many reactionary feminists is the commercialisation of the human body via prostitution, which they somehow seem to regard as uniquely modern or capitalist. Let’s leave aside the fact that prostitution was ripe throughout the very Christian history of Europe. As many early feminists had noted, if a wife was obligated to provide sexual services to her husband in exchange for her livelihood, this was not really that far away from prostitution - at least not in essence. And given that women were severely limited from engaging in the public sphere and become financially independent, this arrangement could easily be seen as having coercive element to it. They were not wrong. In an account from the previously mentioned Matthew Hale, the distinction between a wife and a prostitute is defined not by their substance, but by their legal and societal roles. Being a wife inherently involved the duty to have sexual relations with one's husband, a fundamental aspect of the marital role. On the other hand, adultery, whether voluntary or forced, was associated with the role of a prostitute. By entering into marriage, a woman consented to the role and responsibilities of a wife, thereby rejecting the identity of a prostitute. Practically, this distinction meant that sexual relations with one's spouse, whether willing or not, were considered legitimate and socially acceptable. In contrast, engaging in sexual activities with a man other than one's husband, regardless of consent, was deemed illegitimate and faced social condemnation.

It seems like reproduction being tied to sex didn’t do much in the way of rendering women non-commodities.

Sex being so deeply tied to reproduction created another problem: a cult of virginity, wherein women, even those not at fault, faced severe punishment for breaking it. The 19th-century novel "Tess of the d'Urbervilles" delves into the dire repercussions of the rape of Tess Durbeyfield, a young peasant woman, which forever changes her life and stigmatizes her within a society consumed by an obsession with female purity and virginity. The novel delves into Tess's subsequent suffering, including her ostracisation, the breakdown of her marriage to Angel Clare upon his discovery of her past, and her eventual tragic demise. So much for women being treated as full humans!

But let's entertain the notion, purely for discussion's sake, that all the historical compromises women made were somehow worth it. Yes, some women might have been raped during marriages they could not escape by men they might not have liked. Yes, they did not have any legal or economic rights or means of opposing this. But maybe, just maybe, it was all worth it, in the grand scheme thing of things, as a cure for the thing we’re here to discuss: female neediness. Let’s assume for a second the female need for emotional security is so overwhelming that these are all risks worth taking. But even this would rely on a misunderstanding of what female neediness is fundamentally all about: it’ not simply the desire to be tied to someone that cannot get rid of you because of a Law. It’s a yearning for love, actual love, something that cannot be merely be imposed from the outside through rules. Lana del Rey’s Video Games, to circle back to the beginning of this essay, is not a lamentation of her being abandoned by a fuckboy: indeed, it’s about a relationship. In another song, she asks: “Will you still love me when I’m no longer young and beautiful?”— not “Will you divorce me?”. Because even within relationships, women have different, higher standards with regards to what counts as fulfilling. The data that points in this direction is that women lose satisfaction and sexual interest in relationships faster and easier than men. The funny thing is we have already ran the experiment on whether women simply value sterile security over actual love, the security reactionary feminists think it’s worth letting all our liberation go to Hell for! And the results are in: they do not. In modern times, when they do not depend on men for their very livelihoods, women initiate the majority of divorces - if they simply valued nominal “married” status, they would not be doing this. This suggests that the fact that husbands in the past were tied to their wives without the ability for recourse did not automatically make women happy.

While grossly overrating the benefits of strict norms around casual sex and marriage, reactionary feminists seem to completely underrate the upside of freedom when it comes to love. There’s something most tragic female characters of 19th century literature share: they chose their husbands badly, often at young ages, before they knew better. And the spectre of this decision would haunt their lives forever, tied as they were legally and sexually to that man they made the mistake of saying Yes to. This is the tragedy of Isabel Archer in Portrait of a Lady, of Anna Karenina in the eponymous novel, of Nora Helmer in A Doll’s House. That a bad marriage choice pretty much spelt the end of a woman’s ability to make anything of her life is captured in this passage from 19th century novel Middlemarch3:

"Rosamond, married to the man she had chosen, felt herself to be trembling in the midst of her hopes; her husband, it appeared, did not make a good figure in Middlemarch, and a wife is judged by her husband's success. So far from triumphing in Mr. Lydgate's superiority, Rosamond found it a new grievance that he was not admitted to be so great as she had expected. [...] Her marriage seemed a failure, and she had no strong ties to make her indifferent to failure."

(Middlemarch - George Eliot)

Catherine The Great’s heart was broken by a fuckboy

Catherine the Great, ascending to power as the Empress of Russia in 1762 and reigning until her death in 1796, is often remembered for her significant contributions to expanding Russian territories and her fervent support for Enlightenment ideals (early pro-vax literal Queen).

What is much less talked about is her early life, the moments when she was not the Great Empress we know her as, but a naive and somewhat fragile young woman, a young woman that fell prey to the exact same passions and traps that young women everywhere and at all times have fallen prey to. And yes, that includes being seduced by a fuckboy. The whole affair is described in depth in Robert Massie’s biography.

It’s probably relevant to mention that Catherine the Great arrived in Russia at the age of 17, as a German princess. She was exceedingly eager to please and fit in, learning the Russian language and the local customs. This outstanding willingness to adapt initially ingratiated her with the reigning Empress and the Russian court. But there was a problem. Catherine’s husband, the heir to the Russian throne, who she describes with great contempt in her later diaries, was not interested in her. Instead, he preferred to play with toy soldiers in their marital bed rather than touch her. One must imagine what this felt for Catherine: alone in a foreign country that was notoriously suspicious of foreigners, failing at the main task that was ascribed to her (producing an heir) through no fault of her own. Add to that the personal rejection: Catherine did not love her husband, but she must have felt humiliated as a woman by his refusal to even touch her. It’s no wonder that seven years into her sexless marriage she gave in to the charms of one Saltykov:

Later, Catherine described the path along which she was being led:

“He was twenty-six years old and, by birth and other qualities, a distinguished gentleman. He knew how to conceal his faults, the greatest of which were a love of intrigue and a lack of principles. These failings were not at all clear to me at the time. “

At first, she fended him off. She told herself that the emotion she was feeling was pity. How sad was it that this handsome young man, caught up in a bad marriage now was offering to risk everything for her, knowing that she was inaccessible, that she was a duchess and the wife to the heir to the throne.

“Unfortunately, I could not help listening to him. He was handsome as the dawn and certainly had no equal on this score at the Imperial court. Nor was he lacking in the polish of knowledge, manners and style”

His relentless insistence eventually paid off: Catherine not only started an affair with Saltykov, but eventually fell pregnant with his child. It seems like her husband, Peter, was, weirdly enough, pretty much fine with this. And everyone else at court was rejoicing in the fact that Catherine was finally going to produce an heir. She suffered two miscarriages before finally giving birth to her son Paul. But even then, she couldn’t enjoy her own child, who was taken away from her by Empress Elizabeth right after his birth. She wouldn’t see him at all for almost a week. Jealous of Catherine due to her own childlessness, Empress Elizabeth deprived the new mother from bonding with her child. This resulted in long term damage to Catherine’s relationship with her son. What’s more, her lover Saltykov had grown cold towards Catherine: the whiff of novelty had worn off and he no longer found her that interesting. Saltykov was sent to Sweden where he used his newfound fame as the lover of a Grand Duchess of Russia to charm other women. When he returned back to Russia, Catherine wanted to see him, but he did not even do her the favour of meeting her at the arranged time.

Saltykov was to come to her apartment in the evening; Catherine waited until three o’clock in the morning. He did not come. “I underwent agonies wondering what could have prevented him”, she said later.

I am relating this story for several reasons. Partially, because it showcases how universal this type of drama is. Everything about Saltykov’s strategy would fit in modern times. I found myself smiling at him using his “unhappy marriage” as a way to win over Catherine: that men who talk about their unhappy relationships or how they are “on the verge of breaking up” are not to be trusted is one of the first things I bitterly learned in my young adulthood. Even the way Catherine got over Saltykov is so very modern: she had a rebound with a Polish Count, Poniatowski; a man who could not match Saltykov in his looks and charms, but who was wholly devoted to Catherine and offered her the love and security she was looking for at the time.

The other reason is to highlight that not even royal women were exempt from being treated as commodities. In this entire saga, Catherine was seen by everyone not as a human, but as a vessel for bringing an heir into the world. When her husband did not sleep with her, she was blamed and punished for it. And for all the talk from reactionary feminists who argue that contemporary society has undermined the value of motherhood and the sacred bond between mother and child, it's hard to envision a scenario in today's world where a child is forcibly removed from their mother without sparking significant public uproar.

What is there to be done?

Nothing, there is nothing substantive to be done… At least not by resorting to some top-down control mechanism.

We have reached the end of it in terms of attempts at social engineering and now we are staring at human nature itself, naked before our eyes, frightening in its immense power. Everything has a trade-off: The millions of little heartbreaks women everywhere are experiencing are just a small price we pay for not being stuck in some dead-end marriage with the first man we happened to fall in love with when we were wide-eyed 18 year olds. It’s the price we pay for not being forced into sex against our will in marriages. It’s the price we pay for not being ostracised if we have sex before marrying. It’s the price we pay for the chance of achieving that which we really want: being loved. But if that’s the case, there’s no outside institution, with legible and harsh rules, that’s gonna conjure such men out of thin air. It might be the fundamental tragedy of the human (female?) condition, but not one that can be fixed by an HR department, by the Church, by strict marriage rules, by banning the Pill or indeed, by any number of anti-freedom ideas some might try to convince you are the ultimate fix.

If there is anything at all we could do, then it’s at the level of rhetoric and public discourse; some might even say: Culture. The first thing is what I mentioned in the beginning of the essay: be more open about the truth with regards to sex differences in response to casual sex. In this way women can self-impose stricter norms regarding their behaviour: if they understand from the get-go that casual sex is probably not going to lead to long-term satisfaction, they can self-select out of this activity on their own. A wider recognition of this fact could also lead to the emergence of soft norms in social groups, norms that make women aware of the downsides of casual sex.

The second is a bit more complicated and broader reaching and revolves around escaping the “Anxiety Culture” we seem to be living in. I do think Catherine benefitted from something related to the era she was born in, but that something has nothing to do with stricter marriage norms. Rather, it’s that she did not have the option to wallow in self-pity too much. Most of us do not have the psychology of a woman who would end up revolutionising the way an entire country was run. But there is stuff to learn from the fact that she simply got over her failed liaison, while being in a generally awful situation, went on to depose her husband and become Empress in her own right. In many ways, anxiety expands to occupy the space it’s allowed to. And often, the more we talk about it, the more such space is created. And we do talk A LOT about anxiety, trauma and negative experiences!

Psychologist Lucy Foulkes from the University of Oxford argues that mental health awareness, while obviously beneficial to many, can also have unintended consequences. Specifically, Foulkes suggests that an increased focus on mental health issues might lead individuals to mistakenly believe they are afflicted by psychological disorders, creating a scenario where the belief in having a disorder can manifest into a real issue—a phenomenon akin to a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The first layer is the concern that talking so much about mental health has meant milder problems are now confounded with mental disorders, and young people are diagnosing themselves with problems they don’t really have. Low mood is too readily being described as depression, mild anxiety as an anxiety disorder, and so on. I think this really can be a problem.

I think this argument also holds for the interpretation of personal experiences. The way we frame what happens to us significantly influences our psychological well-being. Labelling every meh sexual experience as a tragic or traumatic event could, paradoxically, inflict more psychological harm than the event itself - and I think there is compelling evidence to suggest our generation is particularly prone to this type of catastrophizing. Would Catherine have become the Empress she would go on to be, had she been continuously told at the time that she had been traumatised?

It’s interesting that feminists of today mostly exaggerate the extent to which women are interested in casual sex, whereas early feminists used to do the opposite; Indeed, they used to paint men as “brutes” who would inflict pain on their wives with their irrational and highly emotional sex-driven nature.

Apart from Middlemarch, all the novels I mentioned were written by men, and some of them very conservative men (Lev Tolstoy). So there is no reason to believe they would have exaggerated the plight of the unhappily married wife.

Interesting essay. I think you're right that the reactionaries can be blind to trade-offs. A lot of the reactionary female intellectuals are smart, insightful, and have hit on something true - but they also seem to be mostly college-educated with flexible, remote jobs in the knowledge economy. I wonder if they'd be so excited about "trad" life if they could swap places with the fundamentalist women I know, who were "homeschooled" (aka pulled out of school to take care of younger siblings and totally uneducated), have no job prospects higher than Walmart cashier, and would face extreme social stigma, even from their own families, if something was going wrong in their marriage. Trad life sounds fun if you've managed to use modern liberal feminism to wiggle your way out of all of the trade-offs first.

This was an interesting article, and I don't really disagree. My issue is with your framing, which, believe it or not, is still the dominant frame of most women in developed countries. i.e. We can't go back to the past because things were horrible for women in the past. There’s nothing particularly *wrong* about your framing, but overall it will lead to bad results on the important values in life for the vast majority of people. Any valid frame needs to consider the interests of both men and women and families.

For most people, forming a stable family and being loved by the opposite sex is their greatest desire even if they don’t realize it early on in their lives. Being loved by the opposite sex implies loving the opposite sex, and people genuinely don't want to stick their loved ones with bad deals for some selfish benefit. So any deal likely has to be good for both men and women compared to alternatives.

When looked at in its totality, it's clear the current arrangement does not work. There's a graph floating around on twitter strongly implying only 50% of women born in the 90s will ever marry. Along with this, birth rates keep going lower. It would actually be appropriate to use the word 'unprecedented' to describe this as this level of involuntary childnessness has literally never happened before in history for women. Men historically have seen much worse but let's set that aside. How could the need to be loved and to have children of one's own be better served in our culture than the one a hundred years ago? The statistics look pretty bad.

The current arrangement puts young people into the chaotic churn of dating in their 20s, focusing on their short term pleasure and spits them out in their 30s when they realize they truly desire to be loved, to love and to have children. Freedom and independence and sexual pleasure are all great, but they need to be tamed because they are not the ultimate values in life. And that 'taming' used to be done by society as whole so that when one is ready to get married, one has already been in the practice of subordinating those desires toward more important ones like family and loving others. Children, if left to their own devices will prioritize candy and fun over learning discipline and good character, but a good society continually nudges and shapes them such that by the time they become an adult, they have quite a lot of experience controlling themselves in order to accomplish higher values. The same is true of young adults in their 20s. A young man or woman who has indulged his independence and sexual appetite with no abandon will actually find it difficult to course correct.

That describes one issue, the issue of people being untrained in virtue because nobody tells them what virtue really is or how their view of virtue will unfold over their lifetimes. The other issue is the mismatch in terms for young men and women. Young men, unless they are very charismatic or handsome, find it difficult to engage in the casual sex their society tells them they ought to enjoy when young. Young women have the problem they don’t very much enjoy casual sex though they can usually indulge it. In our culture, one is expected to get married in their late 20s or early 30s. But many men, who have earnestly believed they wanted a loving marriage their whole youth, suddenly find as they approach 30 that they now *can* engage in casual sex and this is too tempting of an alternative compared to lifelong monogamy with the girl next door. As we mentioned earlier, they have no training in subordinating their impulses for a greater good so they indulge. And, after all, what’s good for the goose is good for the gander right? But if this behavior is not corrected, I believe it becomes permanent and many men get stuck in the eternal enticing promise of putting off marriage to the next year. No doubt breaking a lot of hearts along the way.

These things cannot be handled in isolation since one man choosing to forgo marriage necessarily means some hapless woman has to do the same.

I think these two issues go a long way to describing why marriage rates keep going lower along with fertility rates. The hotspots in our culture where people are still getting married are predominantly religious subcultures where they continually focus their minds on the higher order values and focus their minds away from the lower order values. I think Mary Harrington too is getting at something like this, though in a somewhat clumsy way by attaching herself to the anti-pill cause. The lesson I believe she wants to impart is to ask you whether you are using the freedom afforded by the pill in the way that is good for you (and as a result for your future family) in the long run. I believe these are new problems so nobody really knows what exactly to do about them. I don’t think we should go back to the mores of 1950. My contribution is to point out that any analysis of gender issues *must* take into account both sexes because it is the union of sexes that has life giving vitality and it is the union that most people desire.