State-Subsidized Egg Freezing: A Solution to Declining Fertility Rates?

Robin Hanson has written extensively about his worries when it comes to fertility decline. Recently, he has taken note of the fact that egg freezing could be a potential (partial) solution to this problem. I have been badgering him with this idea for a while now; but hey, better late than never!

He then asks about the Economics of this:

Thankfully, I have some answers to all of his questions. I have written at length about the data we have on the efficiency of egg freezing a few months ago, but I have gained quite a few subscribers since then. In the meantime, Regan Arntz-Gray has written an excellent analysis on the economic feasibility of subsidising egg freezing for young women. So overall, I think it’s time for a recap on what we know about this topic.

Why I am (cautiously) optimistic about egg freezing

The first thing to note is that I think giving women the option to freeze their eggs and utilise them later *is* going to increase birth rates. As Regan notes in her post, “Women are having their first baby later in life1, and one issue with this trend is that it leaves them less time to have multiple kids”. A big part of this delay can be explained by the fact that women, no longer pressured into marriages, take longer to find their spouse and settle down. Besides that, women who have time and education-intensive careers often delay childbearing to accommodate career growth. We have extensive data showing that women in such professions end up having less kids than desired. For example, women in academia are more likely than their male peers to be married without children and even if they do, they are more likely to have less than the desired number of children. Estimates suggest that 1 in 4 female physicians will suffer from infertility, well above the estimated incidence (9%–18%) in the U.S. general population. This is tied to the delay of childbearing:

“On average, female physicians complete medical training at age 31, and the age when most women doctors first give birth is 32, compared with 27 for nonphysicians, according to a 2021 study.”

The decision women make in this regard is a response to the critical role that one's 30s play in career development. Claudia Goldin highlights in her book, Career & Family, how the investments made in this decade can accumulate and result in significantly divergent paths in later life. And extensive childcare subsidies or parental leave is not helping these women much- given how these high-stakes careers are structured, time lost is time lost: generous family policies do not seem to close gender career progression gaps. Another option that I quite like is the idea of reducing training and time spent in school (which seems to be needlessly long, especially in the US). But that’s another discussion.

I don’t see careers or a trend towards taking longer to find one’s life partner go away anytime soon, so giving these women the opportunity to have their desired number of kids when they want them, seems like a no-brainer to me.

The other ingredient in making this a viable solution is whether it actually works, scientifically speaking. As I pointed out in my earlier pieces, egg freezing is quite clever in that it tackles the actual core issue that underlies female reproductive ageing: the ageing of the oocytes. As the plot below shows, women have increasing difficulty conceiving via IVF after a certain age. However, using younger donor oocytes almost closes the gap between younger and older women in terms of chance of conceiving (plotted here as success rate per embryo transfer). Egg freezing essentially means that young women become the “young donors” for their older selves.

So, in principle, due to the fact that other female reproductive reproductive organs are much less impacted by age than oocytes, egg freezing should work. But does it, in practice? As noted in my earlier post where I analysed this:

This is not a straightforward question to answer. The relative novelty of this method means there is much less data available than for classical IVF using fresh eggs. What’s more, relatively few women who store their eggs ever end up using them. But data is starting to come out. Here, I will be focusing on the largest study to date: Cascante et al, 2022. This is a retrospective 15 year study conducted by researchers at NYU Langone Medical Centre. It tracks the success rates of 543 patients undergoing 800 cryopreservation cycles. Not a huge cohort, but the best we have to date. The median age at which eggs were frozen was 38 years old and the median oocyte age thaw (or defrosting) was 42 yrs old. Overall, the eggs were in storage for a median 4.2 years.

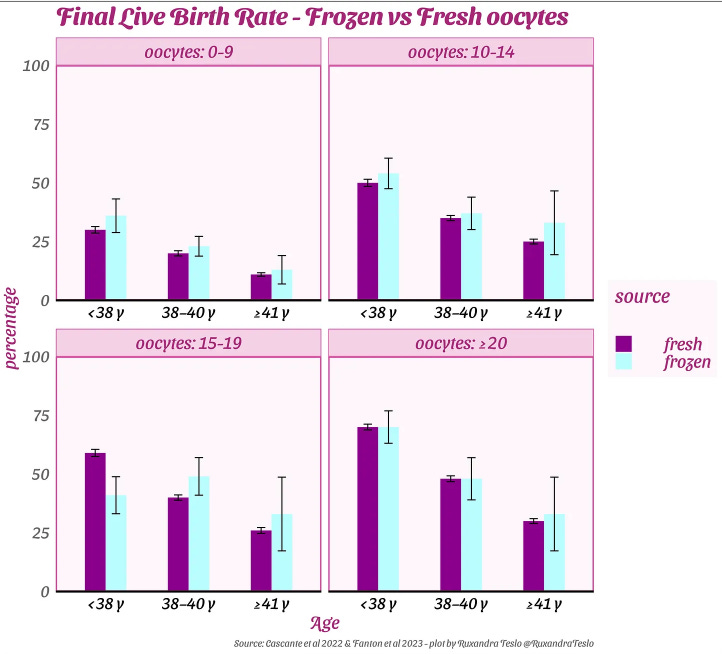

Below, I plotted the success rates using age-matched fresh eggs vs frozen ones. This is not directly from their paper, and I make some assumptions that I detail in my original post if you are interested in checking them.

There are 2 main take-aways from this plot: Firstly, live birth rates using frozen eggs are comparable to live birth rates using fresh eggs of the same age & if the same number of oocytes is retrieved. This suggests that the freezing, storage and thawing procedure does not have a huge impact on the viability of the eggs. In other words, frozen eggs do seem to essentially act as their age-matched fresh equivalents. The second important point is that, like in fresh egg IVF, both age and number of oocytes retrieved matter. At one end of the spectrum, women who retrieve more than 20 oocytes before the age of 38 have a ~70% chance of conceiving. At the opposite end, older women with a lower numbers of retrieved oocytes have a much smaller success rate: only 10%. A lot of media reports focused on the overall live birth success rate (only 39%), but I find that figure somewhat non-informative given the relatively high median age at retrieval in the study (38 yrs old). A much more informative way of looking at the data is splitting by age. The good news is that both age at retrieval and oocyte number can be modified; It’s obvious how you can change the first one; as for the second, more retrieval cycles can lead to more oocytes.

The data above has to be interpreted with the caution warranted by the fact that it’s quite a small study. Nevertheless, this study does look very optimistic to me!

The fact that the efficiency using frozen eggs matches the efficiency of standard IVF is not a consolation for the 30% of women who would still be left without a kid, despite retrieving a high number of oocytes and doing so when young. Of course, some of these women would have experienced fertility problems anyway, although it’s hard to say exactly how many. But the fact that IVF using cryopreserved oocytes and age matched fresh oocytes have similar efficiencies suggests that further improvements to the IVF process are likely to translate into improvements in the outcomes for IVF using frozen oocytes. It also suggests there isn’t something intrinsic about the process of freezing and thawing that makes eggs less likely to lead to a successful pregnancy.

Of course, in order for egg freezing to become an actual option that the majority of women can reliably fall back on if they want to, there are 2 things that need to happen.

Firstly, we need to increase those IVF success rates from 70% to the 90s. Fortunately, there are companies like Vitra Labs and Gameto working on this. And the approaches to enhance efficiency in this process not only promise to make it more streamlined, but also aim to reduce the physically taxing nature of the procedure. This could significantly lower the barriers for young women considering egg freezing. More on this here.

Making the procedure more accessible through reduced costs or subsidies is essential, especially considering that success rates improve with younger age for egg retrieval, yet younger women often lack the financial means to access it. This situation may warrant government intervention (yes, I typed the words “may warrant government intervention”!!!!).

State subsidies sound like a good idea

This is the point where I turn to Regan’s analysis. She is an economist by training; and she provides more reproducible code for her analyses done on Substack Notes than many academics do in scientific papers. Regan has done the work of actually estimating what this would cost (approximately) in this post that I recommend you read:

To quote her:

Plugging all those assumptions into excel (see my work here) and hoping I didn't make any mistakes (if you're interested in this please check my work and/or suggest edits to the model!) I got a cost of $191,000 per marginal baby. This is really high, but also probably worth it. Robin Hanson suggests, given that the average national debt per American is $300-$730k, “We should thus be willing to pay up to these huge amounts up front to induce the birth and raising-to-adulthood of a single child who would then pay average levels of future taxes to repay this debt.” And since the marginal babies from this program would be born to older parents who are more likely to be college educated and therefore likely to make more money than average we can probably expect their babies to be more productive than the average American.

I am under no illusion that this will make a huge impact on its own - we need a multi-pronged approach to tackle the fertility crisis - including and perhaps most importantly a less anti-natalist culture. But at least for the women who are finding it harder to find their life partner or are focused on their careers, this could provide a huge boost.

"“On average, female physicians complete medical training at age 31, and the age when most women doctors first give birth is 32, compared with 27 for nonphysicians, according to a 2021 study.” I've seen it argued that US medical training is longer than it really needs to be, I don't know enough about the field to have a useful opinion on that...but there are a lot of other fields in which the demand for educational credentials and hence for years of schooling is all out of proportion to the true need for and value of those credentials.

Great post and thank you for the plug!

As you said we need a multi-pronged approach which almost certainly includes cultural change and increased status granted to the parents of large families. But also, as you highlight we already know that there's lots of couples who want more kids and are struggling to have them due to oocyte age... so why not start by at least making it easier for those couples to have more babies. Many of the women who wait the longest to have kids are intelligent and ambitious and in good marriages (because they waited to find the right partner) and we definitely want those couples having more kids. And as you say (and as I mentioned in my post as well), convincing those women to have kids in their 20s will be very, very tough without other changes (like the decreased training time for high-status careers that you suggest). I just want to reiterate once more that supporting egg freezing does not imply a lack of support for other fertility increasing policies including those that make it more attractive for young couples to have kids - I got a lot of responses that I think mistakenly assumed these things are zero sum. But I support both things, and agree with you that the marginal babies born as a result of an egg freezing program couldn't easily be shifted to being born to a younger mom.