Is egg freezing the future? A cold look at the data

I perceive the extension of female reproductive lifespan as one of the most significant and potentially rewarding pursuits in biomedical research. Is oocyte cryopreservation a viable strategy?

Erramatti Mangayamma made the news when she became a mother at 73, setting the record for the oldest woman to give birth. There is a catch though: she was not using her own eggs, but younger donor eggs. This means her kid is not genetically related to her. This extreme example is indicative of something very fundamental about female reproductive ageing: It is mainly an issue of oocyte ageing. Other reproductive organs (e.g. uterus) are far less impacted by age-related decline. That’s why Erramatti was able to give birth to a child when she used young donor eggs. And while extreme, her case is not unique.

Perhaps no argument can make my case better than the plot below:

It shows how women have increasing difficulty conceiving via IVF after a certain age. However, using younger donor oocytes almost closes the gap between younger and older women in terms of chance of conceiving (per embryo transfer). This is why any attempt to prolong female reproductive span must put the oocyte at the forefront. I have previously discussed strategies to delay and/or reverse the ageing of these cells.

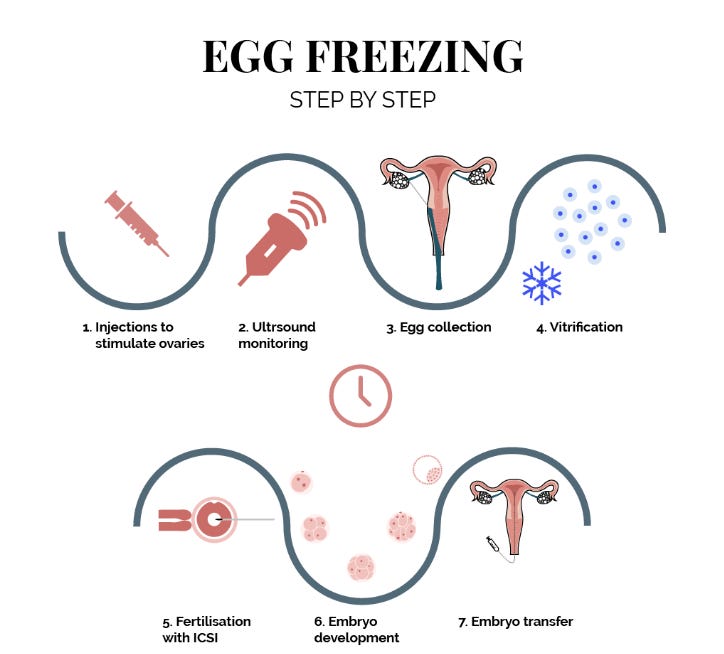

But there is another method, which is already here and many have undoubtedly heard of: oocyte cryopreservation, colloquially known as egg freezing. Fortunately, eggs are biological systems that are small and pretty self-contained; This opens up the possibility of cryopreserving them. The procedure entails using hormonal injections to stimulate the ovaries to produce multiple eggs, which are then retrieved and immediately frozen and stored. When they are required, years later, they are thawed (defrosted) and used in a standard IVF procedure. Ideally, if the process were flawless, they should function like the young donor oocytes depicted in the chart above.

The potential of egg freezing to extend female reproductive span has been identified by women and gradually gained recognition in the mainstream media. Most recently, in this Washington Post article. However, much of the media’s focus on egg freezing centres around individual experiences and the emotional impacts of the procedure. While these perspectives are undoubtedly valuable, there’s a conspicuous absence of coverage on the quantitative and scientific evidence available. I aim to address this gap here and explore area of future improvement.

A way to help women have more children when they want them?

In 1986, Dr Christopher Chen reported the first live birth from a cryopreserved human oocyte. It was only 3 decades later, in 2012, that the ASRM (American Society for Reproductive Medicine) Practice Committee removed the “experimental procedure” label. Even then, they did not recommend the procedure for elective/non-medical reasons; At the time, they advised women to only seek oocyte cryopreservation (OC) for medical reasons (e.g. if undergoing chemotherapy). Despite this, the demand for Planned Oocyte Cryopreservation (POC) procedures raised considerably the following years: a 880% increase from 2010 to 2016. The inflexion point was clearly 2012. Like a dam that broke, the ruling of ASRM let in a flood of women desperate for any solution to prolong their fertility.

This shows a great interest on the part of women for more control over their reproduction. Despite the novelty of the procedure & it not being officially recommended for age related fertility decline, they were still going to try it. In 2017, the ASRM Ethics Committee released a publication stating that POC was ‘ethically permissible’ for women who wanted to safeguard against future infertility due to ‘reproductive ageing or other causes’

This organic increase in demand clearly suggest that women do want more options regarding their fertility. It’s in line with recent studies that surveyed the attitudes of young female physicians. The results are damning and clearly show female doctors are delaying childbearing to accommodate their careers, even at the risk of future infertility. Crucially, the same study finds female doctors OVERestimate as opposed to UNDERestimate their decrease in fertility with age. Similarly to doctors, women in academic STEM report having fewer kids than ideally desired, citing the overlap between key times in career progression & closing of fertility window as reasons. Cruelly reminding & making fun of women for ageing out of their reproductive window is not going to increase birth rates, as some on the internet seem to think. They already know what lies ahead and they CHOOSE to delay.

But extending female reproductive span could do it. It would not be the first time in history when introduction of reproductive technologies helped boost birth rates among college educated women. In her book “Career and Family” Claudia Goldin describes how college women born around 1956, the first to have access to the contraceptive pill, had much lower birth rates than their mothers. This happened partly because they chose to delay motherhood, at a time when the age-related limits to childbearing were not entirely understood. But the next generation actually had an increase in births, despite not having kids any earlier on average. Half of this increase in births can be attributed to Assisted Reproductive Technologies (IVF).

How efficient is IVF using frozen eggs?

So then the question becomes: How efficient is egg freezing?

This is not a straightforward question to answer. As discussed before, the relative novelty of this method means there is much less data available than for classical IVF using fresh eggs. What’s more, relatively few women who store their eggs ever end up using them. But data is starting to come out. Here, I will be focusing on the largest study to date: Cascante et al, 2022. This is a retrospective 15 year study conducted by researchers at NYU Langone Medical Centre. It tracks the success rates of 543 patients undergoing 800 cryopreservation cycles. Not a huge cohort, but the best we have to date. The median age at which eggs were frozen was 38 years old and the median oocyte age thaw (or defrosting) was 42 yrs old. Overall, the eggs were in storage for a median 4.2 years.

First, let’s establish what we are interested in: what is the loss of efficiency for IVF using frozen eggs due to the freezing, storing and thawing procedure? The straightforward way to do this is comparing success rates of IVF using frozen eggs retrieved from women at X age with IVF done with fresh eggs at the same age X.

The study does not do a detailed comparison between the two, so I had to get data on fresh egg IVF success from other articles. Fortunately, there is much more data on IVF using fresh eggs! To make the comparison, I had to settle on a metric for success. Different studies report different metrics. What’s worse, there is often heterogeneity between clinics in how the IVF procedure is carried out. All these factors make a head-to-head comparison of frozen egg vs fresh egg IVF somewhat difficult. In my opinion, the most unbiased & comprehensive metric to use is the Final Live Birth Rate (FLBPR) per patient. This literally refers to the overall percentage of women who walk out with at least a baby after the entire treatment1. I consider FLBPR/patient to be the most appropriate metric because it’s the most practically relevant. Moreover, it does not depend as much on clinic-specific variability in the IVF process. For example, if we were to compare success rates of embryo transfer, another common metric, they would be misleadingly high for the frozen egg study2. That’s because in this study a higher rate of genetic testing of embryos is being performed than usual. Genetic testing is used to establish whether embryos are healthy from a chromosomal perspective before being transferred. This means that the success rate per embryo transfer will necessarily exclude those women who did not have any euploid (or genetically “healthy”) embryo. And since getting an euploid embryo is actually one of the biggest bottlenecks in IVF, excluding these women makes a big difference!

Below is the plot of the comparison between FLBPR using fresh and frozen oocytes. I have age matched standard fresh egg IVF with frozen egg IVF based on the age at which the oocyte was retrieved and stored. This means that most of the women in the <38 yr old category might have actually defrosted their oocytes for fertilisation and use at over 40.

There are 2 main take-aways from this plot: Firstly, live birth rates using frozen eggs are comparable to live birth rates using fresh eggs of the same age & if the same number of oocytes is retrieved. This suggests that the freezing, storage and thawing procedure does not have a huge impact on the viability of the eggs. In other words, frozen eggs do seem to essentially act as their age-matched fresh equivalents. The second important point is that, like in fresh egg IVF, both age and number of oocytes retrieved matter. At one end of the spectrum, women who retrieve more than 20 oocytes before the age of 38 have a ~70% chance of conceiving. At the opposite end, older women with a lower numbers of retrieved oocytes have a much smaller success rate: only 10%. A lot of media reports focused on the overall live birth success rate (only 39%), but I find that figure somewhat non-informative given the relatively high median age at retrieval in the study (38 yrs old). A much more informative way of looking at the data is splitting by age. The good news is that both age at retrieval and oocyte number can be modified; It’s obvious how you can change the first one; as for the second, more retrieval cycles can lead to more oocytes.

If the results from this study hold true in larger cohorts, they bode well for the future of egg freezing. They suggests that the freezing, storage and thawing procedure does not have a huge impact on the viability of the eggs. In other words, frozen eggs do seem to essentially act as their age-matched fresh equivalents. But caution must be exercised when interpreting the results. There are reasons why the frozen egg study success rates might be artificially inflated.

Firstly, there is a selection process taking place here: Women who are undergoing IVF using fresh eggs are more likely to have experienced infertility issues. By contrast, those who freeze their eggs in advance are simply women who wish to prolong their fertility. All else equal, We might expect higher success rates in the frozen egg group simply by virtue of that. Unfortunately, there is no reliable way to get around this limitation of the study.3 The other caveat is that the storage period was only 4.2 years. It is plausible that a longer storage period might lead to lower success rates, although preliminary results suggest longer storage should not have a very large impact. On the bright side, there is also a modifiable factor going in the opposite direction; so driving down the observed success rates of the frozen egg study: The relatively high age at oocyte retrieval. Only 15 women froze their oocytes before 35. We know from data using fresh oocytes that outcomes are better for under 35 year olds compared to 38 year olds. So maybe there is heterogeneity in the <38 group such that younger eggs mean success rates even higher than what we see in this study.

All in all, I think these limitations do not take away too much from the main optimistic message of the study. In any case, there is a point beyond which speculation without empirical data becomes pointless, so we simply need to wait for more studies on larger cohorts and from different clinics.

The Future

The results of the study look promising & open the distinct possibility that in the future, women will be able to freeze their eggs in their 20s and use them later with a high probability of a live birth. But this is not the reality now and improvements need to be made. Firstly, the procedure needs to become accessible for young women. As we have seen, the success rates are highly dependent on the age at retrieval. Secondly, the success rates, even for eggs retrieved at a young age, are not 100%. We need to improve that. And last but not least, higher standards of transparency need to be maintained across clinics.

Making It cheaper and easier

Imagine you are a 35 year old female physician. You have dedicated a long time to training and have a fulfilling career. Now your eyes are set on starting a family and having kids. But maybe you don’t yet have a partner. The biological clock, which you are most likely painfully aware of, is ticking. But in the absence of a father, you decide to freeze some eggs for later. Unfortunately, the data is clear: it would have been much, much better if you would have frozen your eggs in your 20s, as opposed to now. Ideally, when you were still in med school or maybe residency.

However, the age distribution of women seeking egg freezing suggests the established professional is a much likelier egg freezing client than the young medical student.

In other words, the procedure does not usually happen at an age that would maximise its efficiency.

Why might that be?

There are 2 important reasons: cost and the emotional and physical difficulty of the procedure. Egg retrieval is neither affordable nor easy. The average cost is significant : in the ballpark of tens of thousands of dollars including storage. This poses a barrier to younger individuals in particular. Additionally, the procedure is physically strenuous & emotionally demanding: about a third of women undergoing IVF will suffer from mild OHSS (Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome), which mostly manifests as swelling, nausea and discomfort; But 8-10% will manifest a more severe form, requiring medical assistance. The emotional and physical toll of egg retrieval has been widely documented in the media. It's understandable why younger individuals, especially those in their 20s, might be reluctant to go through such a procedure. They typically have fewer resources and are less willing to jeopardise their health for a potential future benefit that seems uncertain. It also makes sense why a more established woman in her 30s might consider it, as the sense of urgency is much more pronounced. However, by then, it might already be too late.

So how do we shift the age curve so that egg freezing is actually done at an optimal age? Simple: Make it Easier & Make It Cheaper.

Fortunately, advances are being made in this direction. For instance, start-ups like Gameto are refining a method known as In Vitro Maturation. In contrast to existing IVF protocols that utilize mature oocytes, this technique relies on retrieving immature ones and matures them in vitro. To achieve this, Gameto’s Fertilo platform uses an engineered line of ovarian supporting cells that aid egg maturation in vitro.

Why this technique promising?

It could make egg freezing less physically damaging and less costly: Retrieving immature oocytes permits shorter ovarian stimulation cycles, making the procedure much less burdensome and potentially more affordable.

It could increase success rates, by allowing the retrieval of more oocytes (as immature ones would not be discarded). As I have pointed out above, success rates increase with the number of oocytes available.

Increasing the efficiency of IVF more broadly

The fact that the efficiency using frozen eggs matches the efficiency of standard IVF is not a consolation for the 30% of women who would still be left without a kid, despite retrieving a high number of oocytes and doing so when young. Of course, some of these women would have experienced fertility problems anyway, although it’s hard to say exactly how many. But the fact that IVF using cryopreserved oocytes and age matched fresh oocytes have similar efficiencies suggests that further improvements to the IVF process are likely to translate into improvements in the outcomes for IVF using frozen oocytes. This is good: it means improvements in IVF might help both couples struggling with infertility and those electing to preserve their eggs. Rather reassuringly, we have seen a steady increase in IVF success rates per cycle since it was first introduced in 1986. The success rates for IVF have increased substantially since it was first introduced. IVF used to have a success rate of only 6% per cycle when it was first introduced; The success rate per cycle is nearly 50% for women under 35 today, which hints at the potential for future improvement. I have written more about what steps can be taken to improve IVF here.

Standardising procedures & increasing transparency

There is a fine line in medicine between UNDER and OVERregulation. If you know anything about me, you know I am unlikely to complain about underregulation. Yet, fertility clinics might actually fall in this category. In particular, I was a bit surprised by the lack of transparency when it comes to success rates at different fertility clinics. For example, the success reports fertility clinics have to submit to CDC contain and extremely sparse and non-informative data! The current scenario imposes an undue burden on patients, leaving them grappling with uncertainty and confusion due to the absence of clear, accessible information. This unnecessary stress gas been brilliantly captured by recent articles. Having a clear picture of success rates of individual clinics is particularly important given that we know there is heterogeneity between methods used by different clinics, which suggests potentially large variation in success rates.

Transparent data sharing is not merely a patient-centered concern; it is pivotal for advancing research efforts. For example, consider a quote from a recent article that tried to analyse egg freezing outcomes:

“While this study provides a broad snapshot of women undergoing OC, it does have a number of limitations, most of which arose from the data itself. International comparison is challenging due to databases having different reporting requirements, standards and access procedures. Intranational comparison was also challenging as reporting requirements changed for the SART database during the period of time we analysed. The temporal mismatch meant some datapoints could not be compared across all years or across nations.”

It highlights the same heterogeneity and lack of uniform data reporting standards I encountered myself.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Dr. Sarah Cascante, the lead author of the egg freezing study for kindly and quickly replying to all my questions regarding her paper. I would also like to thank Beatrice Leydier (@BeaLeydier) for reading this and providing suggestions.

Here treatment is defined as egg retrieval, egg freezing, storage and thawing, followed by IVF.

Indeed, Cascante et al report a 44% success rate per embryo transfer in >41yr olds, compare to the usual ~12% for this age group. This can be in large part attributed to increased genetic testing and exclusion of aneuploid embryos

There are several reasons why I expect the effect to not be huge. Firstly, most of the women who undergo IVF do so due to ovulatory disorders. It is not clear that the quality of the oocyte is compromised by these. Another line of evidence is that, when controlling for euploidy aetiology of infertility does not have an effect on live birth rate.

Great post! A few thoughts from a fertility specialist. Firstly, U.S. data (available at SART.org and from the CDC) shows that live birth rates (LBR) are higher with fresh donor eggs vs frozen donor eggs, which is a better comparison because it removes infertility as a confounder. But this is kind of a moot point because obviously you have to freeze if you are doing this for fertility preservation. Secondly, pregnancy success rates with frozen embryos are greater than with frozen eggs. So, for women who are partnered or plan to use donor sperm anyway, embryo freezing might be a better option. It also allows for genetic testing on the embryo (euploid embryos have higher implantation rates). Obviously this is more expensive than freezing eggs and of course requires that you commit to a sperm source sooner than you would like. Better yet if you make enough eggs, freeze both eggs and embryos! Thirdly, mathematical modeling studies show that the optimal time for egg freezing for women may be early to mid-thirties (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4457646/). Older than that, it's much less successful and for younger women in their 20s, they may undergo the risks of the procedure and expense without ever needing to use those eggs. Another consideration is desired family size. For women who want more than one child and start their families later in life, egg and/or embryo freezing may be even more cost-effective (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36175208/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4457614/).

Great piece! The similarity of outcomes with frozen and fresh eggs shows how much using vitrification vs slow freezing (from 2006+) has helped improve egg thawing rates, making egg freezing a much more viable option. I also like the section on the future and Gameto's work to make IVM success rates higher. Another "moonshot" startup in the fertility space is ConceptionBio (https://conception.bio) who are trying to convert stem cells to eggs. If they succeed the female reproductive span will be significantly extended.