On bad drug pricing research

In which I discuss a paper that is quite representative of the dismal state I found drug pricing research to be in

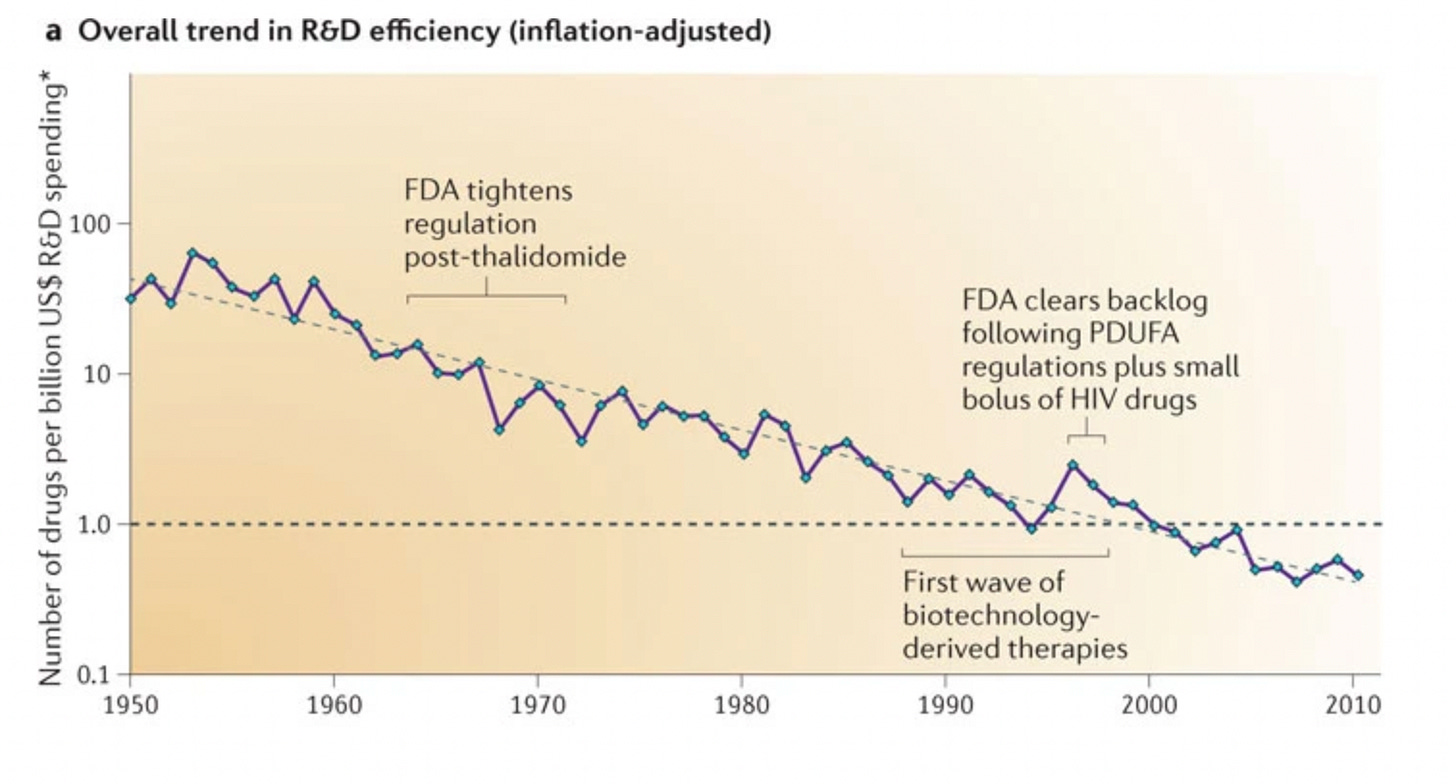

Below is a plot showing how pharma productivity (money spent on R&D vs approved drugs) has changed from 1950 to 2010. You can see an increase in money invested in drugs for less output. This plot is taken from a review from 2012; the authors called this trend of decreased pharma efficiency Eroom’s Law1; They also speculate on the key causes of this decline in productivity

A more recent review (2020) from the same authors shows a somewhat reassuring reversal in this trend since 2012. However, they also warn that we shouldn’t rely on this: unless we manage a more dramatic reversal of the trend, the factors that led to it in the first place will only intensify.

To anyone, and particularly those of us in/adjacent to biotech, this should be alarming. Why?

A lot of scientists work in areas of Biology because we ultimately want medical benefits to get to patients; If Eroom’s Law doesn’t buck further, it will make it much harder for this to be achieved. the increase in drug prices is something that has already gained salience in political debates. Ultimately, we risk entering a negative virtuous cycle where increasing drug prices prompts less investment, which prompts less R&D and so on.

As a PhD student in Biology, I want to understand how this works: Why has pharma productivity declined? How does this affect drug prices? What can be done, at a policy or scientific level to ameliorate this? This means delving into topics ranging from health economics to pharmacology. Unfortunately, what I discovered is that the field is plagued by a phenomenon that makes understanding it harder: researchers often seem driven by a specific ideology often to the detriment of accuracy/ quality.

Some normative assumptions

When it comes to drug pricing specifically, the specific policies one might prefer will inherently be influenced by personal values. At the end of the day, there will always be an affordability vs innovation trade-off. Of course, one can devise better policies that would increase accessibility to drugs while still maintaining a high level of innovation. This is what Peter Kolchinsky proposes in his book, The Great American Drug Deal. Others are focused in increasing efficiency of pharma R&D, which would be a a win-win for everyone: pharma companies, patients, the state.

But at the end of the day there is a simple mathematical consideration that makes completely avoiding the trade-off next to impossible: investing more in research will require money and that money has to come from somewhere. Where exactly that money should come from is another topic of debate, but someone will always be at the short end of the stick when it comes to actually providing that money. And that someone will include the average citizen, whether it’s through taxes, directly paying for drugs or other means. It’s no wonder then that this trade-off consistently creeps up in a lot of debates around how medical innovation should be commercialised (most recently regarding whether a revokation of patents on vaccines is necessary)

To better conceptualise this trade-off, it would be useful to imagine 2 societies standing at extreme ends. At one end a society that optimises entirely for current affordability at the expense of investing in innovation. This is of course appealing in the now, but disastrous for the future. Just imagine how the world would look today if we had stopped medical innovation at the level of what we did in the 19th century. How many of the people you personally know would have been dead with that level of medicine? There is another extreme: one in which people toil away, seduced by the promise of “future progress”, but they never get to experience the fruits of their labour; unless they are part of a very lucky few. Most people would agree that the ideal lies somewhere in the middle of these 2 extremes; we want a balance between ensuring future innovation and also making it accessible in the here and now, not just some hypothetical future. But exactly where you stand on this axis is a matter of personal values and not something that can be decided purely by asking empirical questions.

But that does not mean empirical data has no value in this debate. Even if the preference for one side of the trade-off is something that is inherently subjective, data is not. And it’s in the interest of all parties that the data is as accurate as possible, so that the policies we implement actually have the desired effect. It’s the duty of the researcher to put aside their personal preference for one value or another and present & interpret data in the most objective way possible. This philosophy is part of the value-free ideal of science, proposed by the philosopher W.B. Dubois. If you wanna know more his arguments for why he considers this the right of approaching science, you can look into this comprehensive review of his arguments.

The Bad

The paper I am discussing in this post starts rather ominously. This is a phrase from the abstract, which already betrays a sort of animosity towards pharma companies.

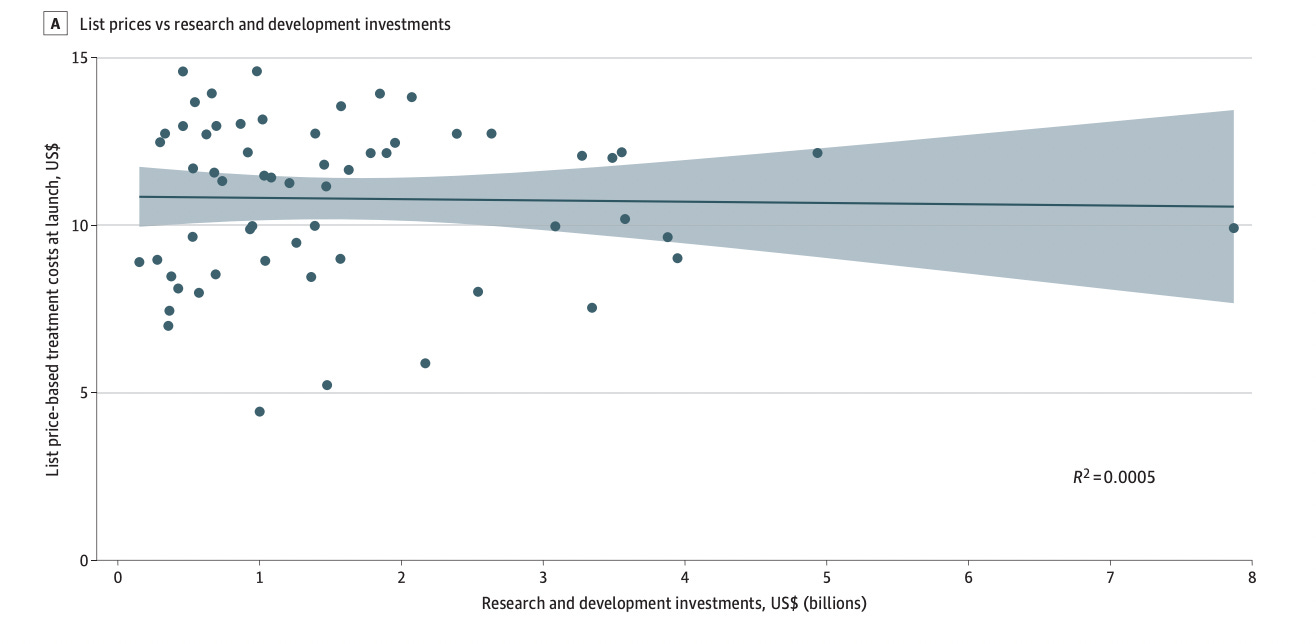

Drug companies frequently claim that high prices are needed to recoup spending on research and development. If high research and development costs justified high drug prices, then an association between these 2 measures would be expected.

But what’s actually bad is that this animosity towards pharma probably contributes to making the authors ask the wrong question, rendering the results of the paper at best, irrelevant and at worst, potentially harmful to policy decisions.

So why am I saying the paper is asking the wrong question? Well, what they are doing is a regression of the price of a drug vs money spent on developing that specific drug. This is the (incorrect) methodology that’s hidden behind the phrase: “then an association between these 2 measures would be expected” from the Abstract.

And why is using this methodology wrong?

Because, by comparing R&D expenditure for a specific drug (& not the entire portfolio) with its price, it completely ignores how pharma works and makes profits.

For R&D to be a sustainable business, the profits from launched drugs have to generate a return on the investments that went into pursuing the entire portfolio that leads to successful drugs, regardless of whatever the costs happened to have been for the successful drugs. This is because the low success of pharma R&D means any approved drug has to compensate the costs for the entire portfolio (hidden costs).

What I wrote above is true because of the particular way in which pharma profits are generated:

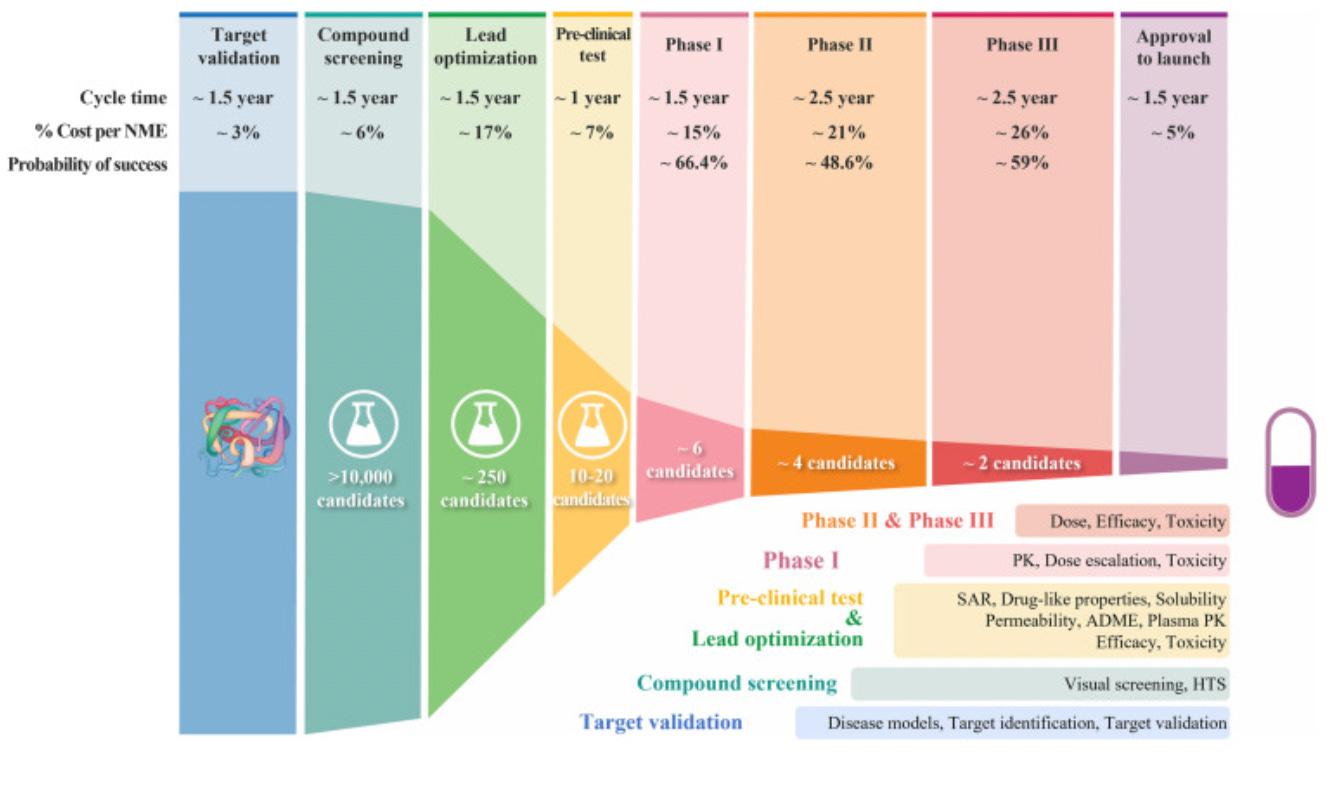

Pharma has a high failure rate. Below is a simplified diagram of the drug discovery process: a long and arduous process. About 10,000 candidates are tested in compound screening for one successful drug launch. Even if we restrict ourselves to compounds involved clinical trials: only about 10% succeed.

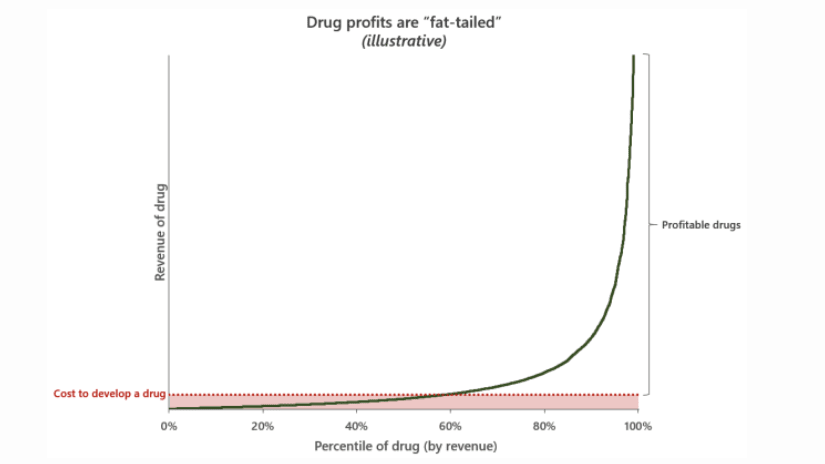

The process of drug discovery and the failure rate at each step Even among drugs that succeed, only a minority actually drive profits. Below I am using this illustration from his excellent blog post about drug pricing to make my point. Alex Telford, an excellent blogger and biopharma analyst makes an excellent point regarding how drug prices. Drug profits are a so-called hits driven business: a few blockbusters make up for the rest of relatively unprofitable drugs and drive further R&D investment.

So the correct question here would be: What happens to the pharma R&D budget to be invested in pursuing their entire portfolio if revenues decrease? Funnily enough, the authors themselves realise this is relevant, but choose to bury this in the Conclusion section of the paper, as an afterthought:

There are other issues with applying this analysis. For example, it ignores the fact that drug prices are set by a market mechanism where the total addressable market that can benefit from a drug is necessarily more important than the specific R&D cost. For example, a drug that can help a minority of patients suffering from a rare disease has to be more expensive to recoup costs compared to a drug that treats a very common disease. The paper also ignores the considerable amount of money that pharma companies pour into early-stage companies that play an important role in the developing drugs.

Conclusion

One might consider such a paper inconsequential in the grand scheme of things. But I think this is not the case. Given the political salience of these topics, such papers can be important in informing policies related to drug pricing (if you’re interested you can read more about the impacts of the IRA on drug pricing here). Papers like this one are used to write the headlines like : “Big Pharma Says Drug Prices Reflect R&D Cost. Researchers Call BS” and similar such headlines in other publications. I think it’s important to hold companies responsible when they make mistakes, but shoddy empirical research can never be the basis of good decisions/ policies!!!

Eroom’s Law is a nod to Moore’s Law. Moore's Law describes the exponential increase in the number of transistors that can be placed at a reasonable cost onto an integrated circuit. Eroom is Moore in reverse, which highlights how pharma efficiency has had the opposite trend compared to the one described above

I built software for clinical trials for about a decade, and in that window, it was pretty obvious to me that the inherent conservatism and resistance to change of the majors (and likely the FDA) was driving a lot of unneeded costs. Better regulatory policy (especially around IRBs) and more effective auditors who could push for quality improvements rather than box checking would make things safer and cheaper.

I wonder whether the first plot depicting Eroom's Law actually tells us much. Is the number of new drugs the correct numerator? Suppose we invented a single drug that cured cancer; by that measure, R&D efficiency would plummet. Of course, if we adjusted for clinical benefit (in QALYs, perhaps?) per new drug, perhaps it would show an even more disturbing drop in R&D efficiency. But that's the sort of evidence that would convince me that things are as bad as people say. Furthermore, measuring trends in clinical benefit would probably be quite hard, precisely because clinical benefit, like drug profit, is fat-tailed. Just as Taleb showed that the fat-tailed distribution of war casualties makes it hard to infer whether the world has become less violent over time, I would expect that the fat-tailed distribution of drug profits would make it hard to have tight confidence intervals around an estimate of R&D efficiency over time.