My ovaries do not have cysts.

On the unaptly called Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

When I was in my early 20s and dating, if I would reach something like a second date with a guy, I’d bluntly tell him: “Hey you know, I might never be able to have kids. Are you ok with that?”. It felt like I had to warn them, lest they found themselves shackled to a barren woman they might find it hard to dispense with later on.

I believed I might be infertile because, at sixteen, I’d been diagnosed with the unaptly named “Polycystic Ovary Syndrome” (PCOS). No one had ever explicitly said I was infertile, but the implication hung in the air, and I accepted it as fact. Still, at the time, I told myself it didn’t matter — who wanted children anyway?

Around the time I turned 25, as career oriented as I was, the idea of never being able to have children started to bother me. I did not want children then, but it seemed like something I would want later. Infertility has been a harrowing spectre for women since biblical times. Hannah wept her eyes out and Rachel let her sister sleep with her husband in exchange for mandrakes that would make her fertile. I did not have a sister, nor a husband for that matter, and I could probably get mandrakes if I wanted to, but that seemed like it would not help. So I went to a doctor in the UK — a private one at that. She was pretty much useless and looked at me incredulousy when I explained that no, I was not trying to conceive, but I wanted to prepare for the future and understand what impact PCOS might have on my fertility. She did not seem to get why I was paying her 300£ for such an unserious matter and said I should come back when I am actually trying for a baby, because nothing is guaranteed. I asked her about odds — but she refused to discuss them: the concept of probabilities seemed to elude her. The interaction was so annoying that at that point I would have let my sister sleep with my husband, had I had either a sister or a husband.

So then I turned to the next best thing, which is “doing research on my own”. After all, I am a biologist, so I reasoned that would help. I went into a deep, obsessive dive into what it actually meant to have PCOS and then into fertility itself. I came away with 4 main conclusions:

Fertility science was fucked: underfunded, understudied, messy, confounded.

Women are gravely misinformed about their own fertility and the existing possibilities for preserving it at a mass scale.

PCOS was not really that big of a deal.

Egg aging on the other hand was a much bigger deal than PCOS. But egg freezing works and it’s something I should probably do.

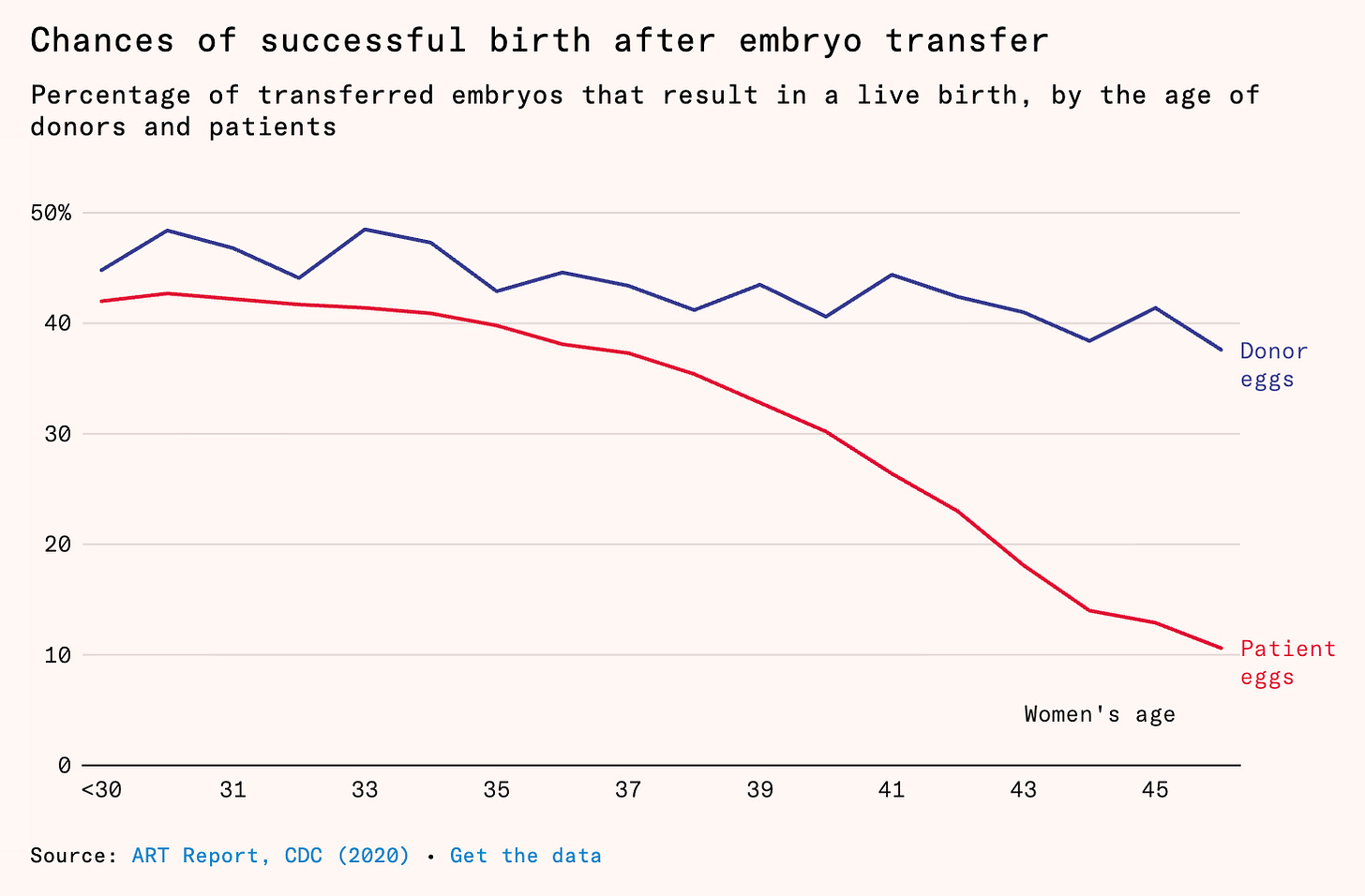

This is actually how this blog was born: some of my first pieces were on the efficacy of egg freezing and the causes of female fertility decline. I have also written a longer article for Works in Progress on the impact that having children has on women’s career and life choices and the fact that being able to extend the female fertility window would be a really big deal for expanding women’s freedom. The piece struck a chord with many. At the core of it might be the following plot, which shows something fundamental about female fertility decline: it is mainly determined by the egg and not the uterus. When older women use frozen and thawed young donor eggs, they have ~ the same success rates as younger women. This is why egg freezing works in the first place: you are becoming your own “donor” for your future, older self.

This is the first in a series of posts documenting my egg freezing journey. First and foremost, I want to demystify the process for women and raise awareness around fertility. But this is also a personal topic, one that gets at the core at what it means to be a woman and a biologist — or, as someone has called me, a “biofoid”. So this is also intended as a personal story, a diary of some sorts of what dealing with one’s fertility means for a woman and how harrowing it can feel to navigate the space of IVF, even when one is equipped with biological knowledge. For a more streamlined version of “How to do it” for the practical minded, I will be writing an article for Works in Progress on egg freezing.

I believe it’s natural that the first piece should start from the beginning: why I thought I was infertile, how I discovered more about PCOS and the fact that no, it does not make one infertile, as well as the very first step in the egg freezing journey itself: the transvaginal ultrasound to get my antral follicle count (AFC)1, an approximation of how many eggs I could hope to get from the process, which in turn is highly correlated with further success.

The misconceptions and contradictions around PCOS are key here and should, I think, raise the alarm bells for people. “What the hell are we doing here?” was my reaction to reading a lot of fertility-related literature. “Why do we not know this basic fact?” was a constant reaction as I was reading on various topics. Maybe some of that sentiment and annoyance can be transmitted by writing.

The monster within my ovaries

Polycystic ovary syndrome… The name itself brings to mind something ominous. My ovaries had cysts... Some monstrous outgrowths were emerging from within my ovary, canibalizing it, crowding it, killing it from inside, like Saturn eating its own son. I was not able to produce kids, my future kids were cysts, I was barren, sterile, an abomination of nature.

At least that was the imagery I had in my mind, when at 16, I was told I had PolyCYSTIC ovary syndrome. But maybe it was also sort of fine, because at the time I was reading The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir: “One is not born a woman, but becomes one”. Maybe the abominations growing inside my ovaries would retard this journey to becoming a full woman, the second, lesser sex; maybe they would spare me from this unwanted fate and I could forever remain a semi-androgynous creature. I was not going to be the first sex, but somewhere between first and second seemed better than second. Maybe…

I got my first period at 14, which is apparently normal by historical standards, but was very late compared to others in my cohort. And the periods themselves took place every 3 or 4 months. Sometimes I would wait for half a year with no “bleeding”. As a result, I might have been one of the few females out there who was happy to get her period: it made me feel less like an anomaly. If I was the second sex, at least I’d better be good at it. But I was not.

I was underperforming at being the already underperforming second sex. On all fronts. No boy in my high school would hit on me. I later pieced things together and I realized it was in large part because I was taking part in these things called “olympiads”, which were very popular in Romania and I was very good (and mouthy) in school — so boys were intimated. Maybe I should have made more of a conversation I had overheard among two boys sitting behind me in class, along the lines of:

Boy 1: “Ruxi is actually very hot”

Boy 2: “Shut up, Ruxi is a genius (genius in Romanian is used liberally), she’d never look at a dumbass like you”

But no, this did not wake me up. At the time, all the movies and “received wisdom” I was perceiving (despite my mom’s best efforts to the contrary) was that my worth was solely determined by my looks. Since no boy would hit on me, my looks must have sucked. Ergo: I would never be loved. No fairytale for me. It might sound silly, but it was as simple as that. The life of a teenage girl is not easy: the surge in puberty hormones in women seems to have the effect of increasing our neuroticism. Perceiving oneself as ugly is enough to strangle whatever glimmer of self-esteem might manage to find its way amidst this unrelenting biochemical attack.

For about 2 years, my mom thought my period situation would stabilize itself. That did not happen, so I started doing investigations. I could not do transvaginal ultrasounds, because the mere thought of it scared me, so I only did echocardiograms of my lower abdomen. The doctor did not observe any monstrous cysts so she said: “No, Ruxandra does not have PCOS”.

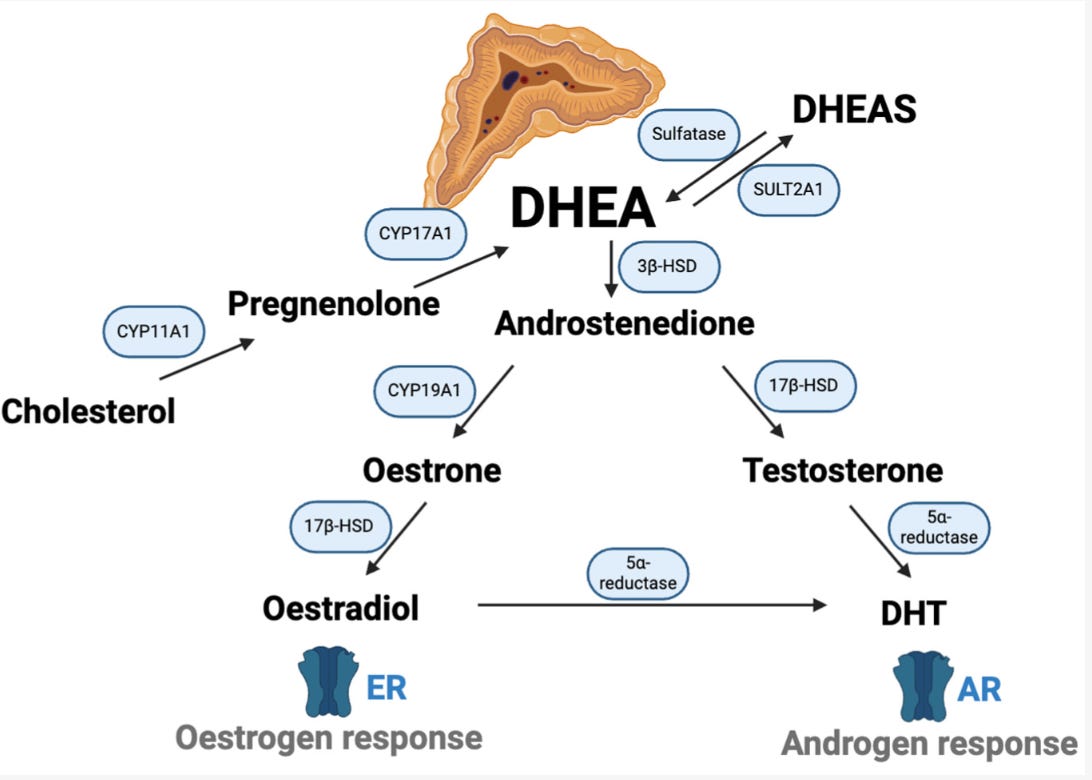

Then I went to an endocrinologist. My dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels, a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal gland, were sky-high. My testosterone and estrogen levels were high too, as a downstream effect of that. I had PCOS, but somehow the person who did my scan missed my cysts. The endocrinologist gave me two options: get on the contraceptive pill (Yasmin) or take androgen receptor inhibitors. I jumped at the idea of the contraceptive pill. It had estrogen so I reasoned maybe it would make my breasts bigger and then maybe, possibly, a boy would deem me worthy of being hit on.

Boys did not start hitting on me, but I did start getting regular “fake periods”, as it happens when you are on the pill, which made me feel a bit less abnormal. But the name of my condition did not. PolyCYSTIC ovary syndrome… You might have trouble having kids…CYSTS…. Infertile…CYSTS… Words spinning in my head. Depending on the day, I was either happy to have been spared the fate of being fully the second sex or devastated that I was nothing clear, but rather an in-between creature, my ability to give life squashed from within by my ovarian cysts. In fairytales, the ugliness of the soul often spills on the outside: that’s why you have the ugly witches. The same was happening to me, why I must have repelled the boys. The ugly witches also had warts and a wart is kind of like a cyst, isn’t it?

My ovaries do not have cysts

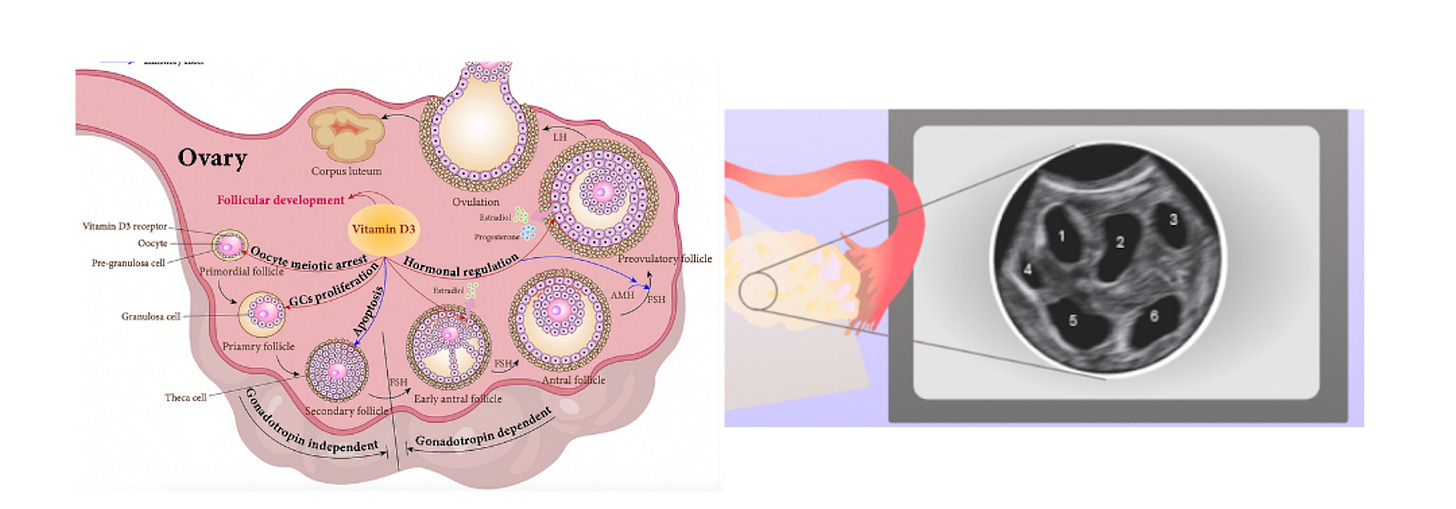

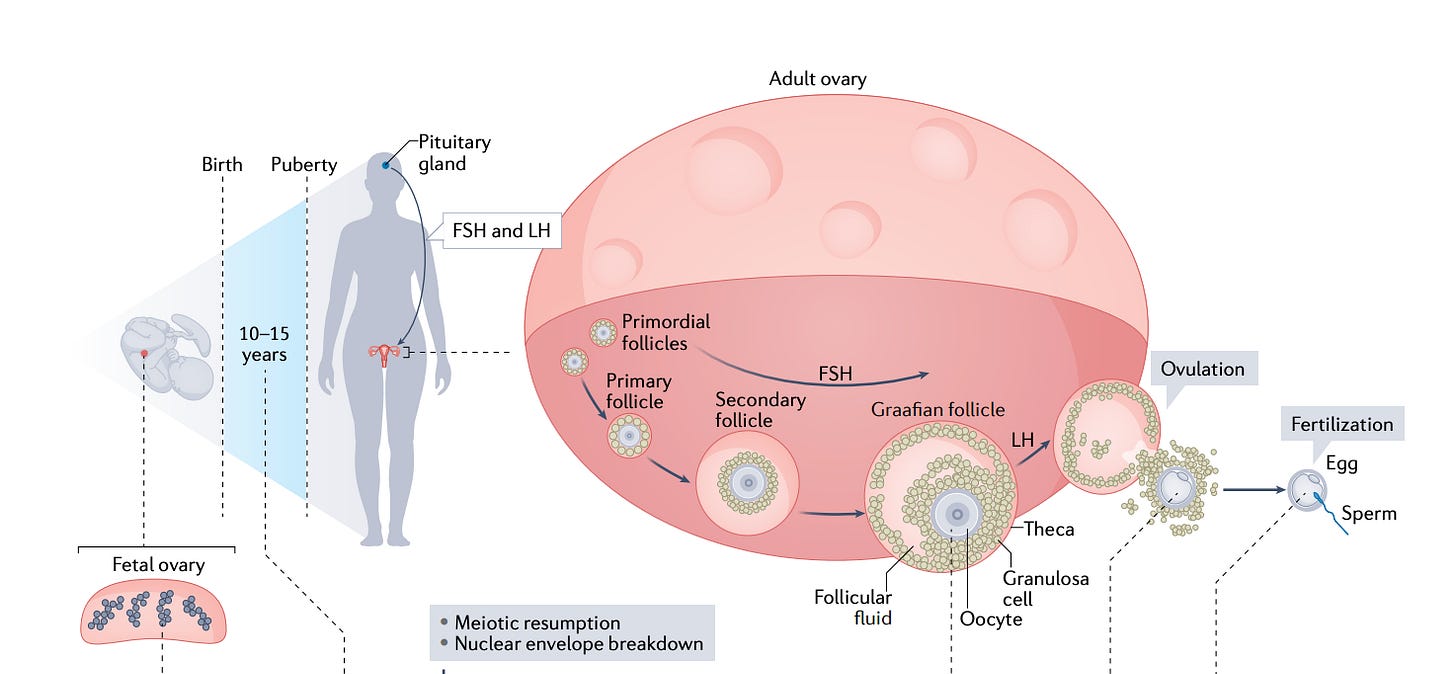

Women are born with all the eggs they will ever have (fun fact: you come from an egg that was once part of your grandmother as she was pregnant with your mother). The eggs, or oocytes, don’t just sit around by themselves in the ovary: they are usually protected by surrounding cells, forming so called follicles. Follicles themselves go through various maturation stages: primordial, primary, secondary, antral and so on. A young woman might have hundreds of thousands of dormant primordial follicles and their number decreases with age, until it hits ~ 1000 at menopause. Primordial follicles form one’s ovarian reserve. Yet, this is not the pool follicles that are “available” for ovulation each month. That pool is the much smaller group of so-called “antral follicles”. Their number is called AFC or antral follicle count. An antral follicle is an ovarian follicle that contains a developing oocyte (egg) and has formed a fluid-filled cavity (the antrum), making it capable of being recruited for further growth toward ovulation.

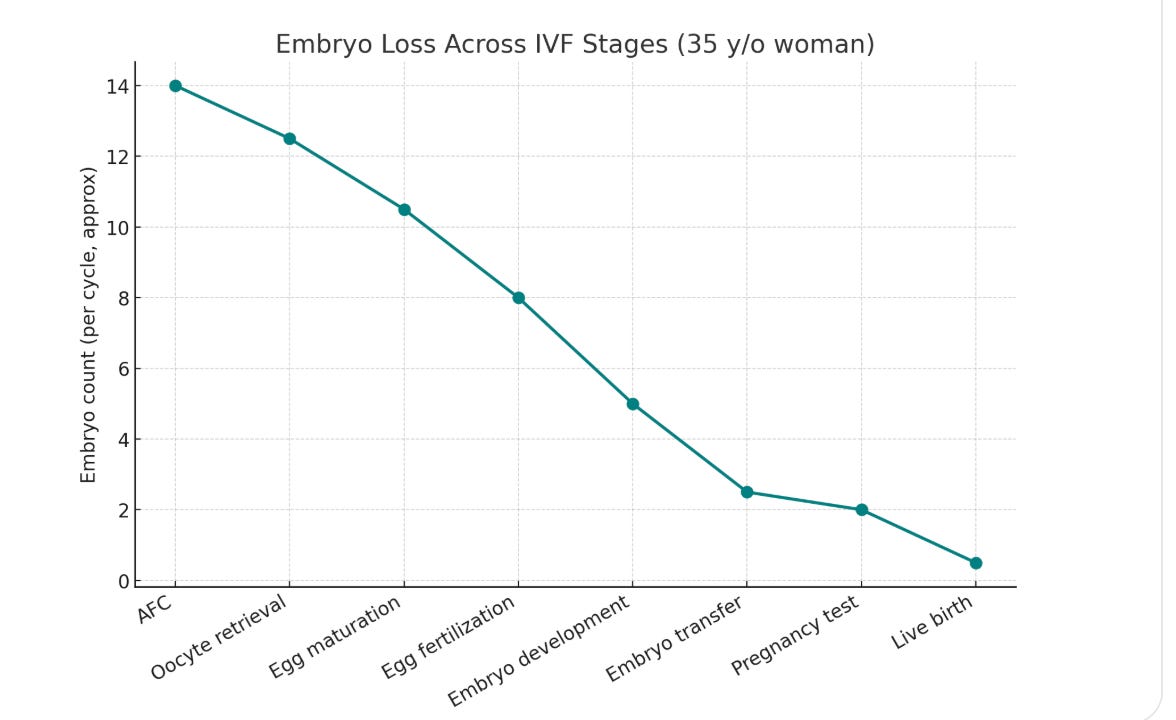

This pool of antral follicles is also important for egg freezing and IVF, because that’s also where you are drawing from when you are doing ovarian stimulation and retrieving eggs. Given the high attrition rate at each step of the IVF journey, the higher the AFC, the better (shown below is an approximate plot for a 35 yr old that has a ~ high AFC for her age: 14). In general, a woman under 30 should probably freeze around 15-20 mature eggs to be almost sure of a live birth.

So more than 10 years after my PCOS diagnosis, I started my egg freezing journey like all women who do: with a transvaginal ultrasound to get my antral follicle count or AFC. My worries about boys had diminished, but a recent event had reminded me, in full force, that I was still a member of the second sex. And catalyzed my decision to freeze my eggs, which I had been postponing. And although my scientific explorations had diminished my PCOS related fears by a lot, I still had it in the back of my head that something anomalous was taking place in my ovaries.

So I entered the clinic where I would have my transvaginal ultrasound paralyzed by fear. Pastel colours, immaculate and sterile: the environment of the clinic felt designed to quell the fears of the women entering its doors. But my fears were anything but quelled. I knew the statistics, especially for older women2. How many hopes must have been crushed in this nice, sterile, comfortable, reassuring environment!

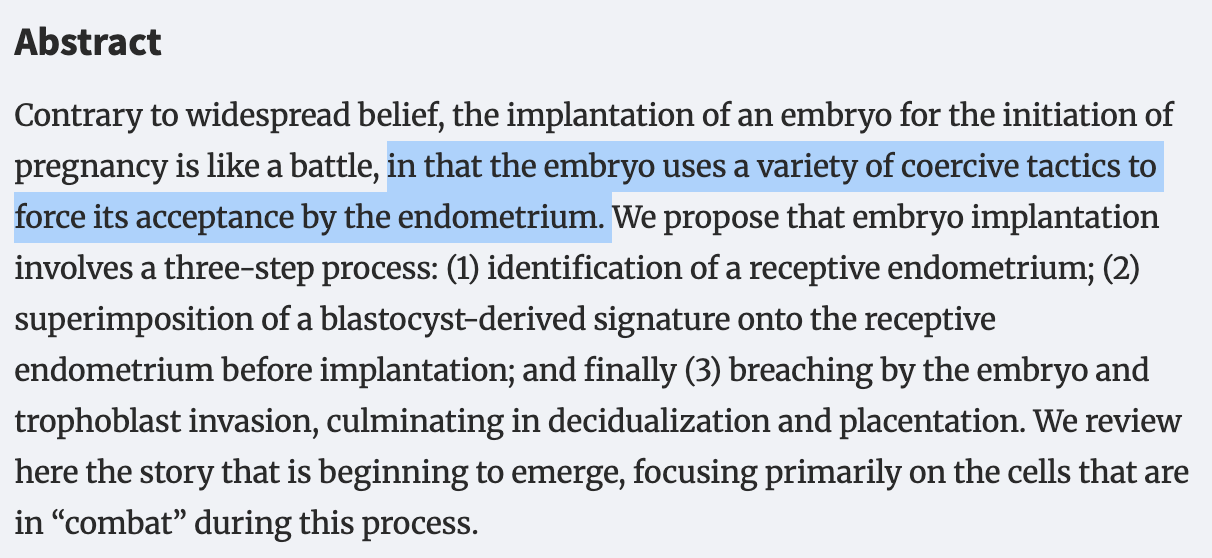

I was informed by the receptionist that a nurse would come soon to attend to me. A smiling, very nice, friendly nurse, I found out soon enough. I ambulated myself to the consultation room. After answering a few questions from the nurse, I started to undress myself, on autopilot. The nurse quickly reacted: she asked me if I wanted some privacy and turned a curtain between me and her while I was undressing. I thought it was funny: she was going to insert a device deep inside my vagina. What privacy was there in all this process? A woman’s fertility journey is a continuous and unrelenting invasion of her privacy, one might even say an attack on it, whether the process happens in vivo or in vitro. Even the implantation of the embryo is an invasion of the uterus, with the future fetus employing mechanisms not too dissimilar from that of a cancer to attach to its mother. But I nodded along: “yes, I want my seconds of privacy to undress myself before you insert that phallus-like object (the ultrasound head) deep enough into my vagina to get an image of my possibly degenerated eggs.”

And I did gain my seconds of privacy before the phallus-like object was introduced in my vagina, gently I must say, by the nurse.

She started with the uterus, which looked normal. I wanted to see my eggs though and I wanted to see them quicker. However, the nurse was calmly and politely taking notes and commenting on the health of my uterus. “I WANNA SEE MY EGGS MY UTERUS DOES NOT MATTER I KNOW IT IS OK”, I was screaming internally, annoyed. But the nurse was nice, so I smiled instead. She finally made a sharper turn of the ultrasound head, a turn that felt more invasive and uncomfortable than the already uncomfortable situation I was in. She pressed the ultrasound head firmly to one of the sides of my vagina. Finally, she was looking at my ovaries; and hence my eggs. And then she gasped.

“Oh my god, do you have many eggs!”. “Is that good?” I asked, momentarily forgetting everything I had read about all this. “Yes, yes it is”. She then started to count. Right ovary: 26. Left ovary: 24. There might have been more of them, but at some point I could tell she was bored and gave up counting. I had at least 50 eggs in my ovaries in total. In scientific terms, that was my antral follicle count (AFC). This was good. Phenomenal even — the average for my age is something around 15. I could not quite believe it though, so I asked again: “no abnormality?”. The nurse shook her head. A consultation with the doctor afterwards confirmed what the nurse said.

The so-called “cysts” in my ovary were no cysts at all. They were antral follicles. On the ultrasound above, they are the black holes in the centre of the image. And the opposite of anomalous growths: they are seeds of life. And, like many women with PCOS, I had many of them, although 50 is high even for PCOS. That was good. It felt good.

I exited the clinic and started to cry. Even now, as I write this, I look at the big round black holes that are my follicles with a vague feeling of affection, as if I was looking at the potential of my future children. They are black, gaping little holes to others, maybe even a bit gross; but to me, they are round and beautiful and plentiful — little black holes full of potential. Oh, how annoying will I be as a mom, showing pictures of my newborn!

That I unnecessarily struggled with anxiety around my PCOS and thought of myself as somehow abnormal, when in reality I had more eggs than I knew what to do with, is a testament to how antiquated, as well as poorly communicated and understood women’s health is.

Why PCOS is not that bad, but age is

The term polycistic comes from an almost century old paper (published in 1935), where authors observed a specific “string of pearls” like appearance of ovaries in women with amenorhea (the absence of menstruation). They called this a polycystic ovary. And because medicine does not like to update itself, the name stuck.

Of course, these are not actual the monstrous outgrowths the name “cyst” implies, but rather immature follicles, or the structures that contain eggs and the surrounding protective cells. Women with PCOS often have more immature antral follicles3, which leads to the above-mentioned “strings of pearls appearance”. And more follicles is actually what you want during IVF.

Why PCOS can be “good” for IVF

In natural cycles, women with PCOS are often subfertile because follicle development “stalls”: several follicles start to grow, but hormonal imbalance prevents one from fully maturing and ovulating.

In IVF, however, ovulation is no longer left to chance. Controlled hormone stimulation can push many of those arrested follicles to mature simultaneously. Instead of being a liability, the follicle surplus in PCOS can actually become an advantage: more eggs can often be retrieved, more embryos can be created and embryologists have a better chance of selecting chromosomally healthy embryos4. In fact, with ovarian stimulation, women with PCOS often do not even have to do IVF.

Not only do women with PCOS not experience worse IVF outcomes, multiple studies even suggest that women with PCOS are somewhat “protected” against the age-related decline in fertility, precisely because they start with a larger pool of eggs. For example, one retrospective study on 1540 older women (>40) undergoing IVF and comparing PCOS with otherwise healthy patients, found that the PCOS-women had a live birth chance per cycle of 26% compared to 15.2% in the normal population.

PCOS is not one disease, but many

That PCOS is called “polycystic syndrome” when no cysts are there is just the beginning of the issue with how we classify this disease. Today, the Rotterdam criteria are used to diagnose PCOS, with 2 out of the 3 symptoms below having to be present:

Oligo- or anovulation: irregular or absent menstrual cycles.

Clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism: symptoms (hirsutism, acne, androgenic alopecia) or elevated testosterone/androgens on labs.

“Polycystic” ovaries on ultrasound: ≥20 follicles per ovary (2–9 mm in diameter) or increased ovarian volume (≥10 cm³).

But this classification obscures more complications. In reality, PCOS is a heterogeneous syndrome with distinct biological subtypes:

Insulin-resistant PCOS

Often associated with higher BMI and metabolic syndrome.

Linked to worse pregnancy outcomes (gestational diabetes, preeclampsia).

Many of the fertility benefits of weight loss (e.g., the reports of women getting pregnant on Ozempic) are mostly seen in this group.

Hyperandrogenic but non–insulin-resistant PCOS

Characterized by high male hormone levels without systemic insulin issues.

Can be further subdivided into:

Adrenal PCOS (high DHEA from adrenal glands).

Ovarian PCOS (the ovary itself overproduces androgens).

Despite these clear biological differences, research rarely stratifies women by subtype. Instead, most research treats “PCOS” as one homogenous condition. This is almost certainly obscuring important differences in outcomes — not just in fertility, but in pregnancy complications, long-term metabolic health, and even how ovarian ageing unfolds. But more on this in another post, on how I ended up managing my PCOS.

Why eggs age (and why this matters)

For a long time, I thought PCOS was the monster inside me that would stop me from ever having children. But after years digging through scientific papers, I came to another realization: the real monster was not PCOS at all. The real monster was time.

Unlike sperm, which men make fresh every few weeks, women are born with all the eggs they will ever have. I was made from an egg that was once part of my grandmother’s body. That’s an awe-inspiring thought — but also a frightening one. Because this comes with a price.

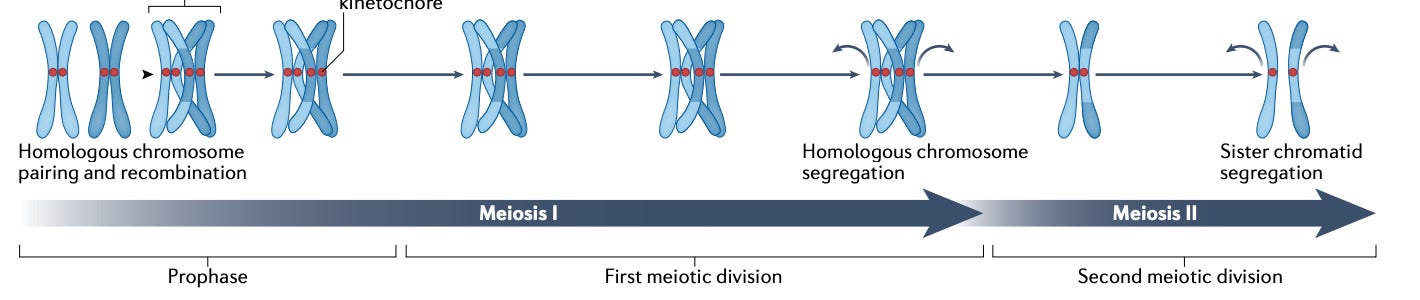

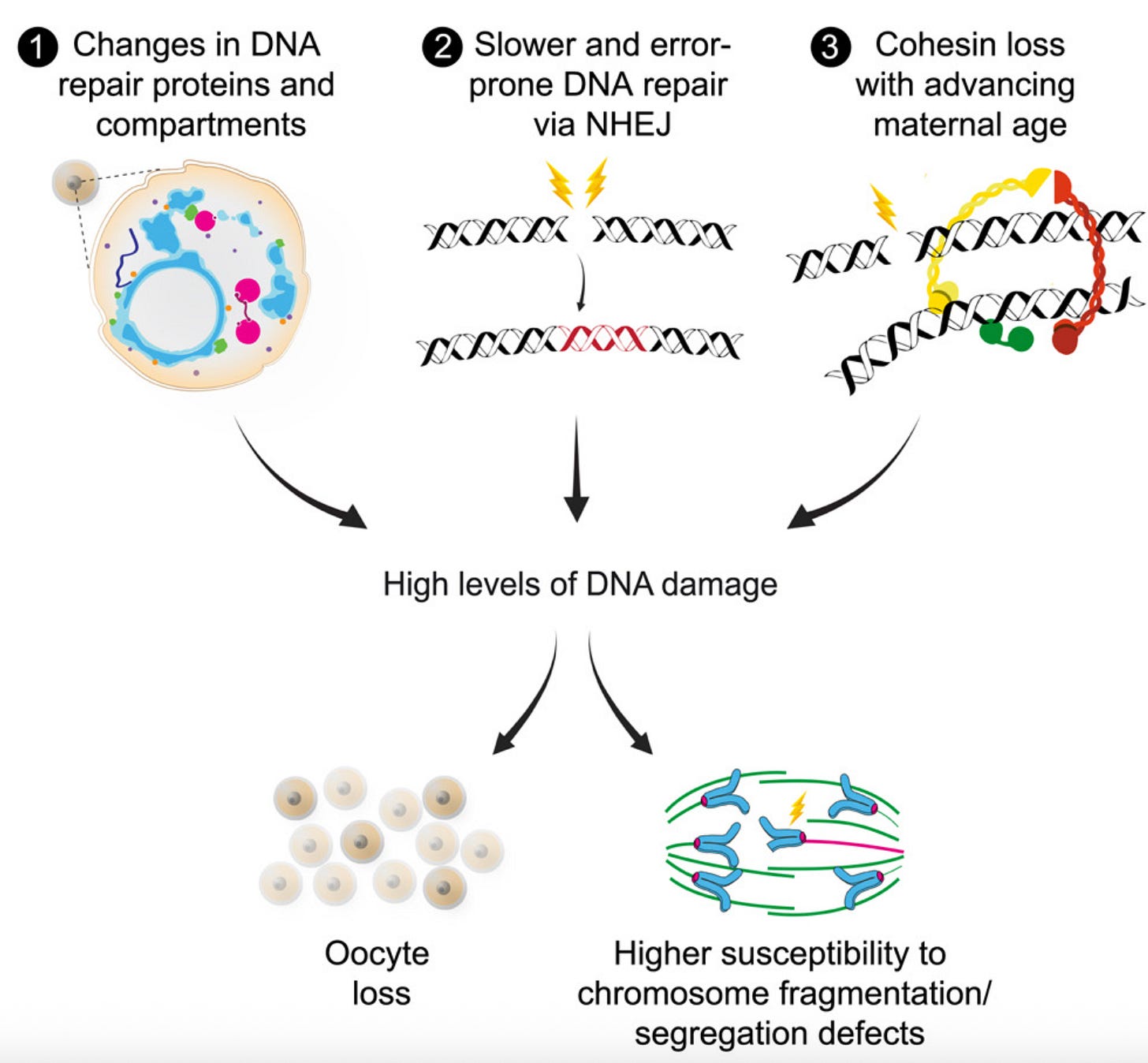

For decades, these eggs just sit there, waiting. But “waiting” is not neutral. This statis means that important proteins are slowly degraded, which has several negative knock-on effects. Perhaps the most important one is an increase in aneuploidy rates, or the proportion of eggs with an abnormal number of chromosomes. This percentage slowly increases with time, accelerating after a woman turns 35 and then even more vertiginously increasing after 40.

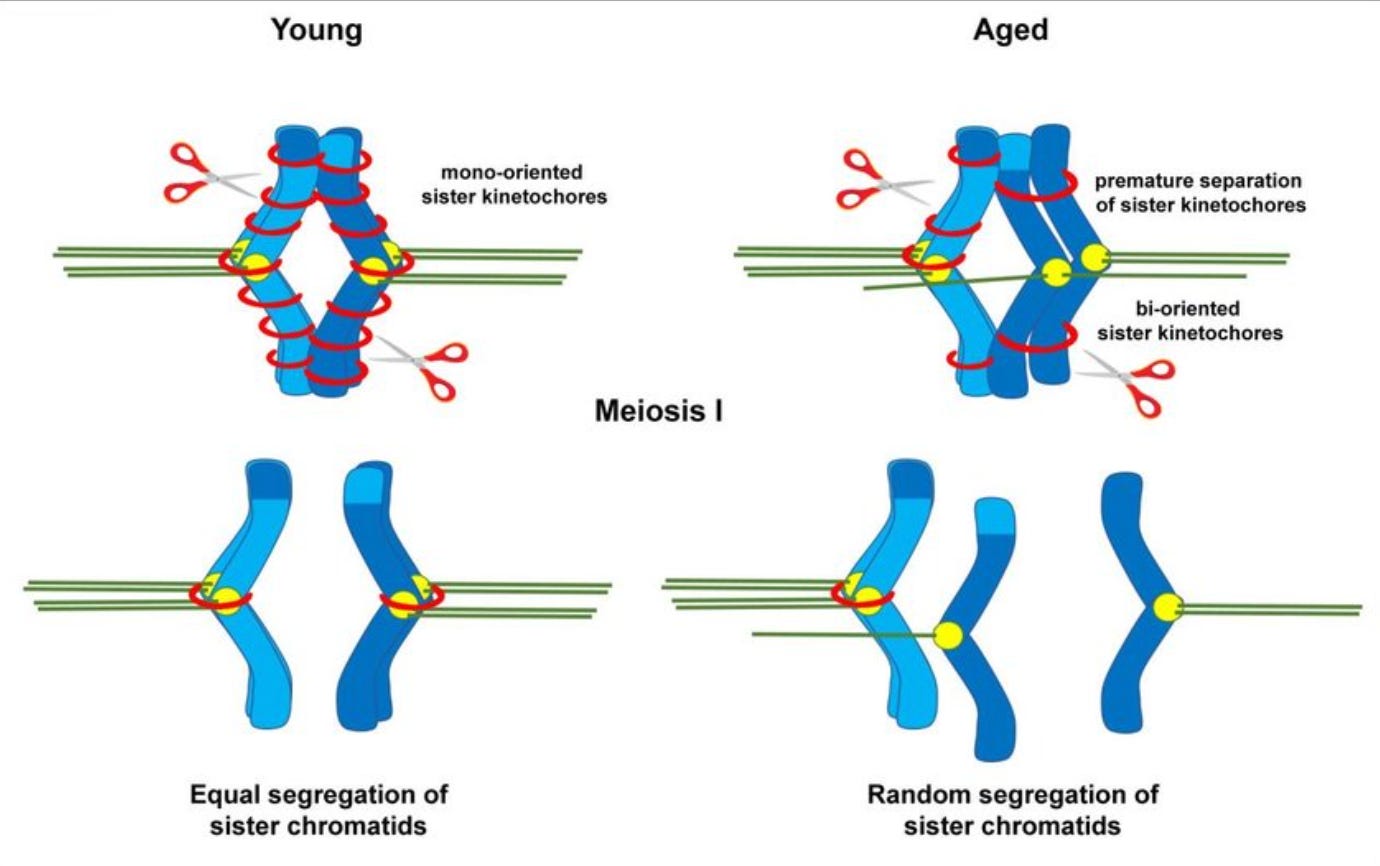

At the heart of this is a degradation of the cell division machinery, which makes sure that chromosomes are correctly partitioned to the right cell during meiosis, the cell division that eggs undergo. This happens for several reasons:

The “glue” that holds chromosomes together weakens. Cohesin, a protein that literally holds chromosomes together until the right time in cell division, degrades with time. This means chromosomes can drift apart too early, causing eggs with the wrong number of chromosomes. Other proteins that “protect” cohesin, like SGO2, also degrade with age.

The cell divison machinery falters. The spindle and kinetochores, which are supposed to help pull chromosomes neatly apart during cell division, also become less functional with age: the egg becomes like a machine with missing screws. As a result chromosomes lag, get missattached, or go to the wrong pole during cell devision.

The DNA frays. Damage accumulates over decades, and the repair systems that used to be vigilant become sluggish. Epigenetic “memory” also fades, like a book whose words are smudged by too many readings.

An increase in DNA damage is also part of why the total number of eggs or ovarian reserve decreases with age: in the presence of DNA damage, primordial follicles “commit suicide”, or in scientific terms, apoptosis. Most of a woman’s primordial follicles or ovarian reserve is thus lost not through repeated ovulation, as many think, but rather due to this kamikaze-like action the eggs undertake.

But there is a way to fight all this: unlike 20 years ago, a woman can freeze her eggs and prevent this age-related decay. If done at the right clinic and enough eggs are collected, this has a high probability of success. We have the tools to defeat the monster. But the journey is not easy: from being able to afford egg freezing itself, to choosing a clinic, to dealing with the side-effects of ovarian stimulation, the burdens are non-negligible. It is with the hope that I can demystify at least some part of this process for young women that I have started this series.

Antral follicle count (AFC) is the number of small fluid-filled follicles (typically 2–10 mm in diameter) visible on ultrasound in the ovaries at the start of a menstrual cycle, used as an indicator of ovarian reserve.

Success rates for IVF per age:

The reasons why are debated and probably vary by type of PCOS.

That being said, there is evidence that women with PCOS can suffer from more pregnancy complications, which is related to the uterus. Again,

What a taut, informative read. You're a wonderful writer. As someone whose partner froze her eggs, this was really helpful. Thank you for writing it.

“I asked her about odds — but she refused to discuss them: the concept of probabilities seemed to elude her.”

Our son was born 14 weeks premature and spent a very long time in the hospital with a number of complications there and when we came home (he’s 18 months old and doing great!). I had this experience so many times. Eventually I settled on “if this happened would you be shocked, a little surprised, or totally unsurprised?” Got some ok answers from that.