The best technology reduces hard trade-offs

A response to a Lyman Stone rebuttal and meditation on what technology is for: reducing trade-offs

Lyman Stone, a demographer and well-known pro-natalist, recently wrote a rebuttal to my “Fertility on demand” piece that I wrote for the magazine Works in Progress. The gist of my article is pretty well summarized in the sentences at its start:

Many women face a choice between career advancement or motherhood. But emerging fertility technologies could allow women to have it all.

That article was accompanied by a follow-up post on my Substack, in which I detailed my thoughts on the social and economic implications of developing technologies that extend women’s fertility windows—and thereby help them achieve both motherhood and professional success, two goals that are often at odds.

I thank him for his piece — I think it was written in good faith and I love a good internet back-and-forth, in the (now) old rationalist tradition. At first, I thought this would be a pretty standard rebuttal, where I just take his points case-by-case and refute them. But then I realized, as I was going through some of his arguments, that we were not disagreeing per se about some important things. For example, we both agree that women “choose” to spend time with their children when they are young and that this is the main causal factor behind the motherhood gap, in a sense. I am not one of those people who thinks men literally force women to spend time with their children against their will or unseen, evil forces (what many would call “The Patriarchy”) “indoctrinate” them to do so from young ages, to their detriment. I do agree with Lyman that this is probably in large part related to biology and the natural instincts mothers have to care for their babies. Yet, we arrive at very different conclusions. And the reason for this, I realized, is that I see technology’s role as fundamentally about reducing hard trade-offs that humans have to make. In this specific case the career/motherhood trade-off.

This will be discussed at length in the second and longest section of my piece: “Choices can only be understood in the context of existing constraints” (you can skip directly to that if you prefer). Before this, because this is still fundamentally a rebuttal, I do need to address a very important mistake Lyman makes, which is that he misinterprets the main point of my initial article — this is a pretty big deal, I would say.

Missing the main point of the article

Straight off the bat, Lyman mischaracterizes the main point I make in my article, by portraying it as if it was mostly about how to raise fertility rates in general. To quote his own tweet about my piece:

Recently, @RuxandraTeslo had a very nice piece at @WorksInProgMag arguing that low fertility may largely be driven by the interplay of biological limits on fertility and motherhood penalties, and that expanded reproductive technology is the answer.

The problem is that this not *mainly* what my article is about — yes, I think enabling professional women to have children in their late 30s (some struggle to achieve that) and early 40s, with high certainty, will help raise the birth rates in this cohort. But this was just one paragraph of the article! My main focus was on affording women more freedom and relieving the immense stress of racing against time in their 30s, especially in “greedy careers”1, where the gender gap is the largest, and which essentially encompass the most prestigious (and demanding) careers in today’s society, including science, medicine, law, business etc. I also emphasized that one’s 30s are critical because they coincide with both a key period for career advancement and the start of declining fertility. Anyway, I will not belabour the points I made there too much — the articles are there to be read.

I do not think Lyman’s misinterpretation was done in bad faith. He thinks about fertility rates and how to raise them day and night, and when someone is so focused on a topic, there is a tendency to interpret everything adjacent to that topic as being mainly about it, even when it isn’t.

To further clarify, I certainly don’t think low birth rates among women in general (so those who are not employed in highly demanding jobs) are caused by greedy careers, simply because these women represent a minority. Most people work regular 9-5 jobs! I also think culture will play an all-around much more important role in determining whether we transition to a higher fertility regime or not — I even wrote about this! And, if we do transition to a more pro-natalist culture, I do believe that extending the fertility window, as well as other tech innovations, might actually help a wider range of women achieve their fertility goals. On the other hand, if we do not achieve such a culture, I do believe the ability to delay childbearing might actually have a detrimental effect on birth rates. This will be discussed more at length in another article. As cliché as it sounds, technology is neutral—it arrives against a preexisting cultural and biological backdrop, and its effects depend on that context.

The fact that Lyman addresses my article as if it was mainly about raising birth rates, even if it it’s not, is a big deal, because his whole rebuttal ends up being centred around something I did not claim.

Choices can only be understood in the context of existing constraints

The first section in Lyman’s article focuses entirely on me misinterpreting one of the studies about the motherhood gap and argues that the gender wage gaps stem solely from female preference, not greedy careers. Because he assumes my piece is about raising birth rates, many of his points seem out of place. For example, when he argues that:

Early fertility only penalizes wages for women who go on to get educated. But a recent study suggests that for less-educated women, there’s no wage benefit to delay.

Again, given that my piece is specifically about women in demanding fields who want to achieve both professional success and their fertility goals, this sentence makes little sense as part of a rebuttal to what I actually wrote! Now, there might be some women that do not go on to get an education, who are very ambitious and end up with stellar careers (think of Thiel Fellows or someone who starts a business without any college degree or is entirely self-taught etc.). But those are a rarity. The correlation between higher education and having a greedy career is pretty strong. While these would be easy points for me to score, addressing each one of these arguments in detail would render this piece repetitive and boring, since they all miss the mark by addressing a point I never made.

Now, let’s do the real work and get into the meat of the problem: are motherhood penalties simply a result of female preference or are they related to greedy careers?

I think both things are true! And I don’t mean this just in the sense of “women with conservative beliefs prefer to be SAHMs or do not prioritize work as much and they are the population that drives the gender wage gap”, as Lyman points our here:

U.S. states with more gender-progressive social attitudes among women have smaller penalties: waaaaay smaller. The most progressive states have penalties just 1/3 the size of the most gender-traditional states (though this is partly due to underlying demographic differences).

I mean in the sense that even very ambitious women, who start off with the goal of being high-achievers in their careers, end up wanting to spend time with their children. This is why policies related to childcare, which Lyman brings as evidence against my points, have been shown to not make much of a difference in Austria in terms of reducing the gender wage gap. The funny thing is Lyman cites the same study that I read and which led me to make this argument in my original article, and is related to the point Scott Alexander makes in his “Society is fixed, Biology is mutable” 2014 piece:

Governments have worked to address gender pay gaps by introducing maternity and paternity leave, creating preschool programs, providing tax benefits to parents, and more. These policies have helped, but they are limited in what they can achieve so long as women continue to have children during the years most critical to their careers (…) People often think that solving problems via biological means is nearly impossible, whereas behavioral and social interventions are merely very difficult. But this isn’t always the case. The social solution to obesity, for example – changing the formula of high-calorie foods, instilling new eating habits in people, and discouraging unhealthy eating – has failed in country after country. By contrast, semaglutide and other GLP-1 agonist medications have been found to reduce body weight by an average of 20 to 30 percent while reducing the risks of cardiovascular and kidney disease and extending lifespan. After 2020, when they started to be used for weight loss, the adult obesity rate in America began falling for the first time in over forty years.

So I am very much aware of this! And I am very much aware of the fact that women want to spend time with their young children — I am not imagining a world in which invisible entities or men or employers or “The Patriarchy” literally force women to stay at home with their children instead of working 60 hr weeks as scientists or CEOs or whatever. I acknowledge women, presumably due to biological differences, the burden of pregnancy etc, want to spend time with their children.

But there is a huge trade-off here, one that many women in greedy careers find it hard to navigate, and which I describe in my follow-up piece:

But men *are spending* more time with children than ever before1! However, no matter how much social conditioning one might desire to impose upon the world, the simple reality is that women seem to enjoy raising their own children and that they probably will always, on average, spend more time with them. This is not a bad thing! Children are great and cute and delightful (except for the times when they are not, but that’s another story).

Yet, it is also true that falling behind in one’s career can be extremely frustrating for women who have spent large amounts of time dedicating themselves to building said careers. Because the gender wage gap is more than just about money: it’s about satisfaction and a feeling of accomplishment and enjoyment. It provides many with a sense of meaning and belonging in the world. Furthermore, it is well known that many careers become more interesting and less tedious as one climbs the ladder. And if that never happens, the way one experiences one’s job will be severely affected.

To illustrate this more concretely, let’s think of a woman that has trained as a scientist. By the age of 34, she has dedicated around 16 years to this pursuit, probably working much more than the standard 40-hour week. She is clearly someone who is ambitious and loves what she is doing for a living. Yet she is also aware that pushing the boundaries of when she is going to have children might cost her having children at all. Let’s consider two paths she might take regarding her life:

she decides to have children at this age and she also feels a biological urge to spend time with them while they are babies: this will take her away from applying for grants and establishing an independent career at a crucial point in her career. When she returns back, she would have fallen behind her male colleagues, and often irreversibly so. The life of someone who has achieved independence in science is very different from that of someone who has not and career structures are pretty rigid about when such milestones can be achieved. For the remainder of her professional life, this woman will have to pay for having taken care of her children when they were young — which also happens to be a massive good for society.

Was this her choice? Yes, it was! Is it sad? I think so. And if we can alleviate the trade-off, if we can allow this woman to have children at say, 39, with more certainty (at the moment it is quite hard to predict which women will and will not be able to conceive relatively later in life), after she has achieved independence, I think this is a good thing. Many trade-offs throughout history have been alleviated by technology. For example, if your only option for surviving winter was to make your own clothes from sheep’s wool in order not to die of cold, I am sure you would spend as much as 40% of your time doing that, and it would be a choice you have made, under the constraints of existing technology. But given that we now have the means to mass-produce coats, people usually choose not to do that! It could be the same about women choosing to delay childbearing in order to reach career milestones.

she decides to prioritize her career, thinking that she can have children later. She starts trying to conceive at say, 38. It turns out this is already too late for her: even with IVF, her follicle count is too low, she cannot retrieve enough eggs. The whole thing is painful, mentally taxing and at the end of it she might still remain childless.

I know many women in both categories. Both types make choices, under the constraints of the existing tech, and both types are ultimately responsible for the outcome of their choices. But that does not change that the outcome can be distressing, in either case. And you do not need to simply trust me that these two scenarios are common in certain circles.

In 2023, the journal Science published an editorial about a scientist, Dr Svetlana Mojsov, who, despite having been crucial to the early work on GLP-1 agonists, had been largely excluded from acknowledgements and awards related to these drugs. For those not in the know, GLP-1 agonists are the “miracle drugs” that work against obesity and whose success was so impressive that sales from one of them single-handedly boosted Denmark’s economy significantly. This is how important people in the field remember Dr Mojsov:

Now in his late 80s, Habener remembers Mojsov as an important collaborator. “She was involved in the beginning, pioneering work,” he says, “deciphering what the real active GLP-1 peptide is.” And Mojsov’s ability to quickly and accurately synthesize large batches of peptide “put us a leg up” on some fierce competition

But after the birth of her children her career stalled. She never ended up establishing her own lab and ended up working as a Staff Scientist for someone else:

At Rockefeller, she joined the lab of immunologist and future Nobel laureate Ralph Steinman, initially as an assistant professor. Mojsov had a toddler and an infant, and “that takes time away,” she says. “One has to balance with young children the career you’re about to start.” (…) Ultimately, Mojsov found a scientific home in Steinman’s lab; she stayed for more than 20 years, until his death in 2011.

In science, laurels and prestige usually accrue to those who rise to the position of principal investigator (PI), not necessarily those who did the legwork or were crucial as PhD students/postdocs. Had she become a PI and worked in this field, it is much more likely (yet not guaranteed), that Dr. Mojsov would be recognized now. Did she make a choice for which she is responsible? Certainly! Does she feel unhappy about the lack of recognition? It certainly seems so, based on what she says herself:

“I think it’s a question of integrity” for people to speak up, says Mojsov, now in her early 70s. “I still don’t understand how I was excluded.”

That does not mean she regrets having kids or spending time with them — this story just exemplifies how the price women pay for their caretaking role can be really high. There is extensive evidence that many women find themselves in the situation portrayed above and that in greedy careers, this reduction in hours following the birth of children is what drives the gender wage gap. Claudia Goldin’s book “Career and Family” is replete with examples of studies which show this. She also summarizes her and others’ research related to this here and here.

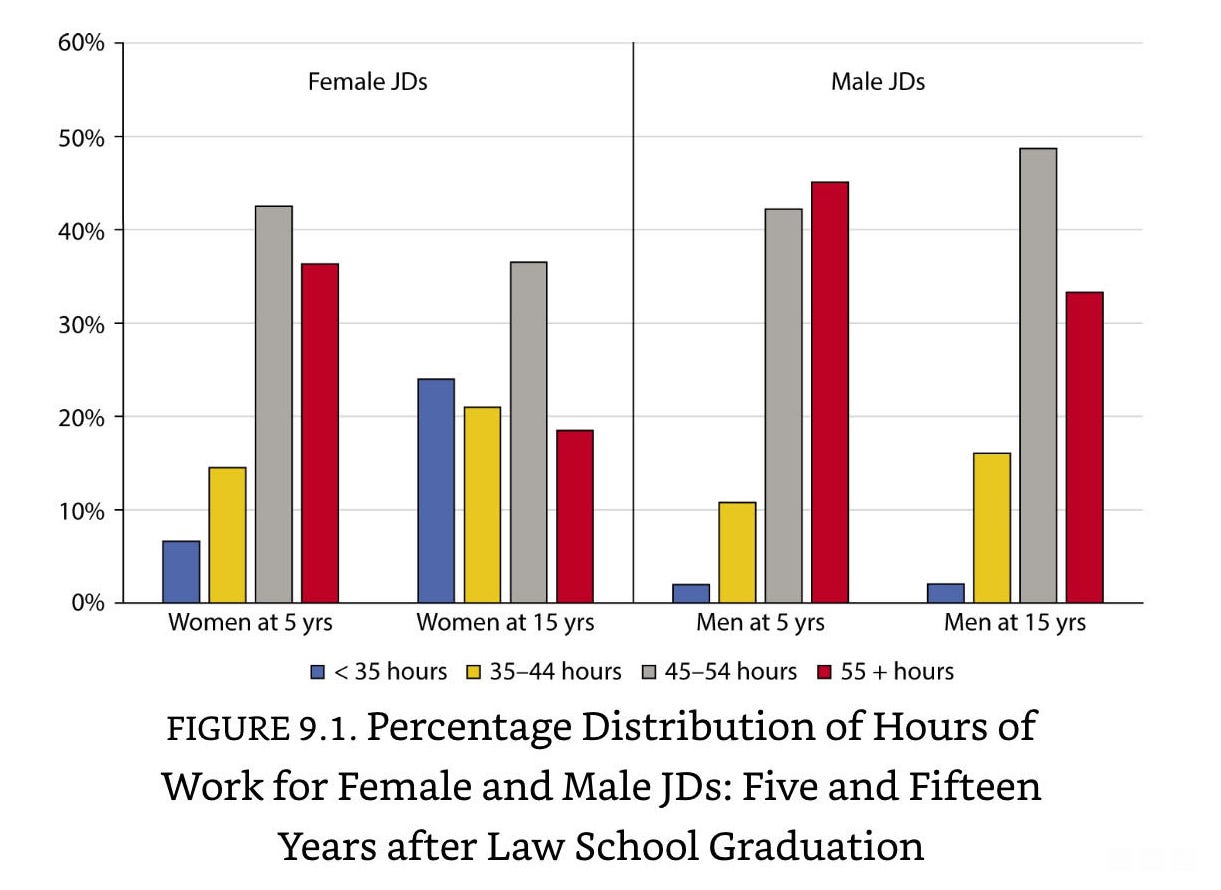

One of the most illustrative studies in this article is covered in my “Fertility on demand” article, and looks at MBA graduates — so Lyman is a bit misleading when he focuses so much on his original rebuttal on the Henrik Kleven study that I mention. *That* is a general study about the motherhood gap. Goldin focuses quite specifically on greedy careers and, as I said, brings up several studies to back up her assertions. This plot, from a “Michigan Law School Alumni Research Dataset”2 , is particularly striking to me:

It shows hours worked by female and male JDs five and fifteen years after law school graduation. From the start, there are slightly more men who work really long hours (55+), which is consistent with the hypothesis, that I also mention in one of my articles, that men tend to be more driven by financial success than women. However, the difference becomes huge at fifteen years. At this point, I need to emphasize that this is a longitudinal sample, which means that all those who are in “at 5 years” columns are also in “at 15 years” columns .

Do we really think all those women working 55+ hours 5 years after graduation suddenly decided they want to adopt super-conservative values and that they do not care one bit about their careers? Or do we think they are more like Dr. Svetlana Mojsov: caught between loving their children, with the kind of love only a mother can feel and the desire to advance in their careers, and achieve external recognition? My bet is most of them probably fall into the latter category.

Now, someone raised a good point in response to my article on their Substack, which was:

I’m not sure if I fully understand her argument though, because it sort of implies you are going to compete in the greedy career, and then after making partner/tenure/exit, have your children. This sort of implies that the entire point of “making it” is so you can coast, which is weird because then what was the point of competing in the first place? Similarly, if fertility extension comes with other biological improvements like mental acuity extension, then your career is going to extend alongside your fertility. So this is really more like a backup for someone who goes into the greedy career and doesn’t quite make it, whereas someone who does succeed will still need to choose between their children or career at some point.

And this is exactly where my “importance of one’s 30s” comes in, because this is when “greedy careers” tend to reach so-called “escape velocity” (for the individuals that do end up achieving it). By “escape velocity” I mean that one pretty much establishes themselves in a way that is hard to counteract even with a little break afterwards.

Let’s think of the famous blogger Matthew Yglesias, who has one of the most successful Substacks out there, Slow Boring. He is 43. Now, let’s imagine a universe where he decides to take two years off and go to the Bahamas, write nothing at all, and completely disconnect from the world. This counterfactual Matthew Yglesias would certainly suffer career-wise from this move: earn less, become overall less relevant/talked-about, compared to a Matthew Yglesias that stays on his current trajectory and does what he is doing. However, I do not think that, after coming back from this two year long vacation, the counterfactual and presumably much more relaxed Matthew Yglesias would have trouble finding a job. And I do not mean *any* job. I am sure he would have plenty of very good opportunities. This is because his career has already reached “escape velocity” — lots of people *already* know him and admire the quality of his work. If the same Matthew Yglesias did this in his early or even mid 30s, maybe his career would look very different now.

And now, going back to my point about women: given the importance of one’s 30s for greedy careers and our current uncertainty about which women can conceive in their late 30s/early 40s, I think having the right technology would simply alter their choice landscape in a very life-defining way. They could, to borrow an overused phrase, “have it all”. And I believe, ultimately, this is the role of technology: that of alleviating the very hard trade-offs that humans have had to make since the dawn of time. The stock picture for this article is that of peasants working in the field with little in the way of modern mechanical tools — an arduous, physically taxing and presumably not very rewarding job. I am sure that faced with the choice between this and starvation, most of you would probably choose to work in the fields. Thankfully, modern technology has saved most of us from making these choices. And hopefully it will do so, in the future, for women who want to pursue both their careers in their 30s and have children!

“Greedy careers” is a term coined by Nobel Prize laureate Claudia Goldin and refers to careers that are greedy for the employee’s time and pay more per hour to the people who work the most. Consider a corporate lawyer working on a deal. The initial hours are spent getting familiar with the material and the people involved. Later hours – once the lawyer understands the case – are much more productive than those at the start. A person working a 40-hour week in this scenario does more than twice as much work as a person working a 20-hour week. Lots of careers are like this.

Includes JDs who graduated from the University of Michigan Law School from 1982 and 1992 and who were in the survey in year five and year fifteen. “At 5 years” and “at 15 years” mean years since receiving a JD. The group is a longitudinal sample, so all who are in “at 5 years” columns are also in “at 15 years” columns (this is quoted from Goldin’s book).

As someone who takes your side of this debate 100%, I’d like to add that this post was a master class how to disagree: on the merits, respectfully, and giving your interlocutor the benefit of the doubt where possible.

Thanks, I really appreciate this. Here's a story for you: A most esteemed Tenured Phd from a Land Grant agricultural school took 3 years off in the late peak of his career to do a mission when he was about 60, then walked right back into his job when he returned. It never occurred to me until now, after reading your rebuttal (not the piece, tho), that this was actually a lot like waiting until you got tenure to have a kid. I'll note that the woman who most capably filled in for him while he was gone has still not had a child. Maybe soon, idunno. None of my business either way.

My wife was 39 when we married. She had a MS (just a BA for me) and a nice career just starting at the University, but quit it to marry me, and now we are biz partners! No kids was our decision, but even so, she said we could try right away if that was a critical thing for me. Guess it wasn't, no regrets.

Anyway, why shouldn't women have more time to make such decisions, this guy got to wait until he was 59 to take a 3 year hiatus! All you are asking for is 49! Seems more than fair.

And as far as whether or not that increases fertility, who cares and who's counting? Have kids if you want, don't if you don't.